In more ordinary times, the high season for Lagos’s art scene runs through October and November. This year, as in other cities across the world, major events have been scaled back and directed towards a local audience, with an emphasis on smaller physical events and online presentations. But disruption in Lagos has not been solely due to the pandemic. In the first weeks of October, the city was brought to a standstill by the decentralized social movement #EndSARS, which saw Nigerian youths take to the streets across the country to demand an end to police brutality and bad governance. Members of the art community mobilized, joining protests on the ground and drawing outside attention through their social media channels. Following the fatal shooting of at least twelve protesters on October 20 by the Nigerian military, the art community has shown solidarity: postponements and program modifications as direct response.

The major events in the city’s calendar include the LagosPhoto Festival, ART X Lagos art fair, and (every odd year) the Lagos Biennial, all spearheaded by artists, cultural producers, and entrepreneurs who have, over the past decade, developed innovative, context-responsive platforms for the city’s contemporary art scene. The first week of November traditionally serves as the city’s unofficial art week, creating a dialogue across venues on the mainland including nonprofits Centre for Contemporary Art Lagos and Museum of Contemporary Art Lagos, and commercial and alternative spaces—among them Rele Art Gallery, kó Gallery, African Artists’ Foundation, Omenka Gallery, Art Twenty One, Treehouse, and hFactor—on Victoria Island, Ikoyi, and Lagos Island. Following the protests ART X Lagos was postponed, as a press release stated, “out of respect for the lives lost,” and is now set to take place as an entirely virtual fair in December. A new addition, New Nigeria Studios, will showcase works documenting the recent protests by photographers including Etinosa Yvonne, David Exodus, Ifebusola Shotunde, Grace Ekpu, Anthony Obayomi and other recipients of the fair’s funded initiative for 100 photographers at the frontlines of the #EndSARS movement.

At the newly inaugurated kó gallery, founded by Kavita Chellaram, collector and founder of Arthouse Contemporary, Thebe Phetogo’s “blackbody Composites” explores figuration and a politics of blackness drawing on the artist’s experiences growing up in his native Botswana, and on time spent in Lagos earlier this year as an Arthouse resident. The exhibition takes as a starting point the scientific “blackbody”—in physics, defined as a surface capable of absorbing light of every wavelength—and goes on to reference liberation struggles against apartheid in South Africa, Nollywood, Igbo masquerades, organized labor exploitation, and nineteenth-century minstrelsy traditions in the US. Phetogo paints with oil, acrylic, and shoe polish, the latter reclaimed from its history of use in exaggerated caricatures of blackness by non-black performers. By connecting past and present injustices directed at Black folk, these works highlight that oppression is cyclical, and permeates every aspect of modern life. Paintings depict black figures against vivid green backgrounds resembling the chroma key screens used to create visual effects in digital filmmaking. In blackbody Composite (In Protest) (2020), a group of men, women, and children take a knee with their fists raised in a stance now synonymous with protest movements from Black Lives Matter to #EndSARS. On the other hand, blackbody Composite (Back to back) references the movement of Igbo masquerades, as incorporated into works by Nigerian Modernist Ben Ewonwu, an artist whose work inspired Phetogo during his Lagos residency. The resulting portrait conveys the gestures of a masquerade whilst seemingly emerging from behind a green screen, as if moving between real and imaginary worlds.

At the nearby Rele Gallery, Tonia Nneji’s exhibition “You May Enter” invites the viewer into an intimate engagement with female pain via the artist’s own experiences of living with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome, a hormonal disorder common among women of reproductive age. The walls are painted a deep red in one gallery and yellow in the other, exchanging the sterility of the white cube for a warm and contemplative environment well-suited to these highly personal paintings. Exploring Christian belief systems and communities of care formed around the experience of emotional and physical trauma, the works feature figures painted in indigo and midnight blue hues (a combination of acrylics and oils) who tenderly embrace, or gaze contemplatively. In See Through 2, a forlorn female face looks out at the viewer with her hand on her head, as if in defeat, or disbelief. A standout work, Sooner or Later, sees two abstracted figures embrace, fusing bodies and limbs while seated on stools draped in Ankara fabrics emblazoned with popular patterns and the logos of local church societies. These reference the artist’s search for religious-based cures, as well as the valuable commodity of the textiles Nneji’s mother sold to finance her daughter’s treatment. The fabric also reintroduces the artist’s recurring use of forms of shroud—as concealment, a place to hide, or as a protective layer to bodies in the process of healing. Nneji’s powerful portraits make visible the pain women are too often encouraged to hide away.

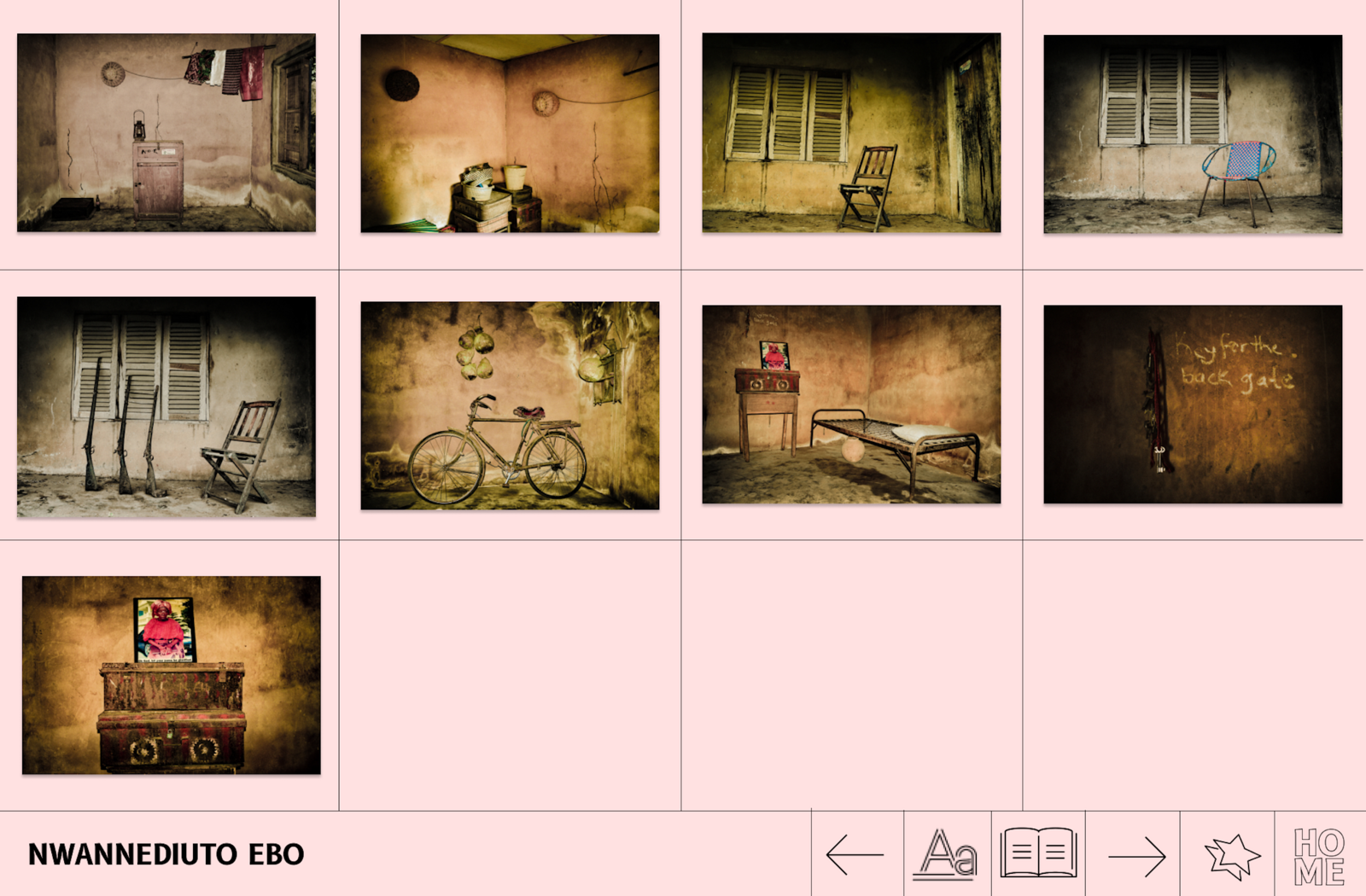

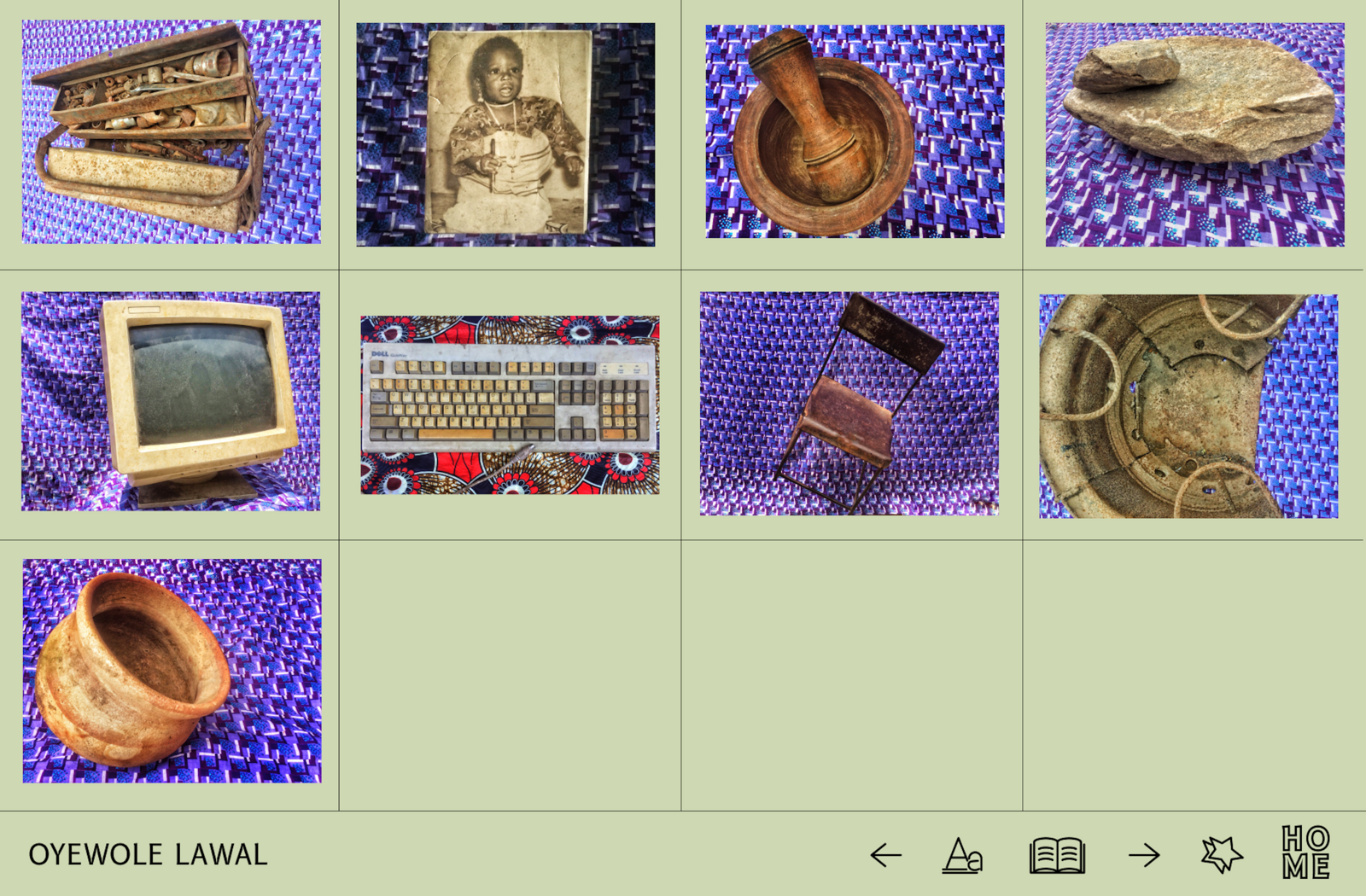

Like ART X, LagosPhoto moved online for its 11th edition and launched “Home Museum,” a concept proposing possibilities for citizen-led and inclusive future museums. The idea was developed from ongoing research into restitution and museum collections in Nigeria, led by the founder of LagosPhoto, Azu Nwagbogu, and curator, publisher, and cultural historian Clémentine Deliss, with guest curators Oluwatoyin Sogbesan and Asya Yaghmurian, while collective Birds of Knowledge are responsible for the site’s design. The result is a digital museum, exploring expanded notions of home through the documentation of objects from around the world by over two hundred participants from the African continent, the US, South America, China, Russia, and Europe. Participants were selected through an open call in the summer to photograph objects of their choice that are of personal, familial, or historic importance—walking sticks, cameras, watches, vases, old coins, photographs, a lantern, clothing. These are presented alongside a short text describing their reason for selection and their significance.

Discussion of Lagos’s art scene in recent years has often heralded a renaissance: new institutions, exciting art being produced in the city, complemented by auction-shattering prices for Nigerian and its diaspora artists. The #EndSARS movement has already seen new, socially engaged artforms emerge, among them a collective live painting intervention initiated by Chigozie Obi and Kéhìndé at the Lekki protest sites, and more via social media. Rather than Lagos being treated as yet another stop on the long list of international art-world destinations, it remains to be seen whether such initiatives garner wider attention, catalyzed by the renewed political awakening of young people and activists fighting for Nigeria’s social, cultural, and political future.