A psychiatrist friend once told me that most psychotic patients believe that they will see the apocalypse. If this argument is valid, nowadays either everyone is psychotic or the end of the world is really nigh. As a pessimist, I think both are possible.

The 16th iteration of the Istanbul Biennial, “The Seventh Continent,” is an exhibition about this deadlock. By considering the rise of fascism, misogyny, and the environmental crisis as indicators of this process, the exhibition displays the tragic results of human hubris but does not stop at this point. It creates new experiences and encounters to overcome the existing crisis. This biennial is not only an attempt to criticize society but also an attempt to establish new forms of being.

“The Seventh Continent” takes its name from the Great Pacific garbage patch—a gyre of mostly plastic debris, roughly 3.4 million square kilometers large, adrift in the Pacific Ocean. Curator Nicolas Bourriaud describes the exhibition as an anthropological study of this human-made territory. But the titular continent is more than an artificial landscape. It is, he claims, a way of living, a system of thought that has reached every part of contemporary life and attests to the inverted relationship between nature and culture. With the rise of the Anthropocene, Bourriaud suggests, culture dominates. Rather than attempt to overturn the nature-culture dyad, however, the biennial aims to destroy such binary distinctions entirely.

In Relational Aesthetics (1998), Bourriaud tried to define a form of art that established new ways of interaction between subjects—human subjects, that is. “The Seventh Continent” is an attempt to expand the definition of the subject by incorporating other entities: humans, plants, animals, trees, rocks, minerals. Unlike the traditional definition, these “others” are not a passive but an active force, subjects that have the ability to speak, affect, and change their interlocutors.

The biennial’s main venue is the Painting and Sculpture Museum of the Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University, a huge, four-story former warehouse on a waterfront in the center of Istanbul. The exhibition is articulated around two main conceptual paths, which deconstruct deeply rooted narratives that have shaped contemporary society. These paths aim to expose power relations and their bitter consequences and to build new understandings. They operate dialectically by triggering new encounters between humans and other entities. A substantial number of works are concentrated here, and almost all of them have their own rooms, which allows them to constitute their own worlds and opens the exhibition to endless possibilities.

Several of these environments are doomed. David Douard’s abject sculpture Gold and smile (2019), for example, alludes to the formlessness of the modern subject with its jumble of magnets, aluminum, metal chains, plastic, and ceramics. En Man Chang’s video installation Ungrounding Land – Ljavek Trilogy (2018) focuses on unseen human labor and the forced displacement of the proletariat subjected to urban planning decisions of the Paiwan Ljavek community in the port city of Kaohsiung in Taiwan.

Other environments are more hopeful. Among them is Extrakorporal (2019), a sculptural installation by the duo Pakui Hardware (Neringa Černiauskaitė and Ugnius Gelguda), which considers body augmentation in the age of synthetic biology and regenerative medicine. Eva Kot’atková’s installation Machine for Restoring Empathy (2019), made from pieces of fabric, offers a protected environment for people, animals, plants, and objects that are wounded or incomplete.

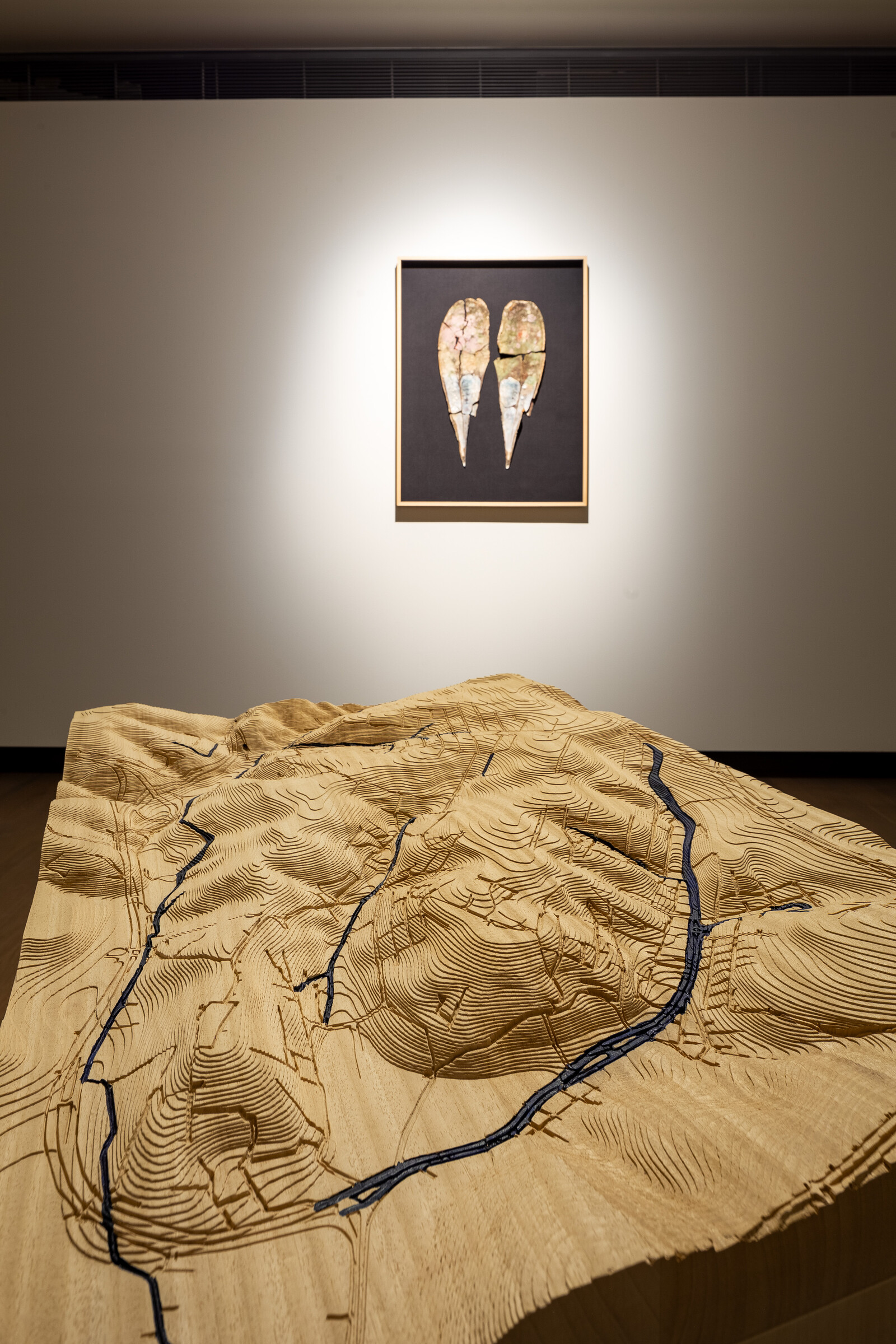

Many of the works on display, whether they present images of a declining environment or dreams of promising futures, are composed of waste, but they are often delicate and precisely deployed. Elmas Deniz’s consideration of the destructive effect of urbanization on Istanbul’s water supplies (History of a particular nameless creek [Pinna Nobilis], 2019) draws attention the beauty of the lost ecosystem of the ancient site of Gryneion, close to where she grew up. Deniz’s work is among those in the exhibition that use beauty to reclaim and recycle the surfeit and waste produced by consumer societies.

In accordance with its institutional identity in which arts and crafts are combined with historic collections of painting and material culture, the Pera Museum hosts works with a historical claim. In contrast to the museum’s permanent collection, most of these works represent an invented history, undermining the concepts of history and identity. Among these is Norman Daly’s Civilization of Llhuros (1972). It consists of an immense collection of artifacts, sculptures, costumes, songs, maps, jewelry, and other items that were assembled to attest the culture of the Llhuros, a fictional society invented by the late artist and educator. Where Daly jammed the codes of anthropology, Charles Avery uses it to investigate the possibility of living in the Anthropocene by pursuing his long-term project inventing a fantastical fictional island (The Island, 2004–ongoing), here presented in the form of a large installation displaying elements from the daily life of the island’s habitants.

During the Ottoman Empire, Büyükada Island in the Sea of Marmara was a Greek Orthodox summer resort. Although it retains an air of imperial grandeur, today it is mostly a tourist destination. The biennial’s presence here assumes the form of a series of journeys in which artists encourage viewers to make imaginative leaps through time and space. Two works stand out. Glenn Ligon’s installation From Another Place (2019) combines two neon pieces with Sedat Pakay’s documentary film on James Baldwin’s stay in Istanbul in the 1960s—translated into Turkish for the first time—alongside other video pieces in which Ligon revisits Baldwin’s steps in the city. Armin Linke’s detailed project Prospecting Ocean (2018), meanwhile, documents the complete entanglement of scientific, economic, political, and technological agendas in the exploitation of the deep sea.

Back at the Museum of Painting and Sculpture, visitors are welcomed by Worlbmon (2019), an installation by duo Güneş Terkol and Güçlü Öztekin that hovers above the exhibition’s three venues. Composed of large-scale paintings and drawings, colorful flags, curtains, plywood benches, and other structures, Worlbmon dilutes the dichotomies that the exhibition seeks to complicate—culture and nature, evil and good, old and new, reality and fiction—into one another. The space it creates becomes a decentered ecosystem that allows for incompletion and fragmentation without attempting to impose categorical identities upon viewers. One reading of it is that it offers an opportunity for viewers to come together with their companions, offering a space in which to build inclusive micro-communities. This biennial, which begins with distressed representations of the world, ends with a soothing feeling.

.jpg,1600)

.jpg,1600)