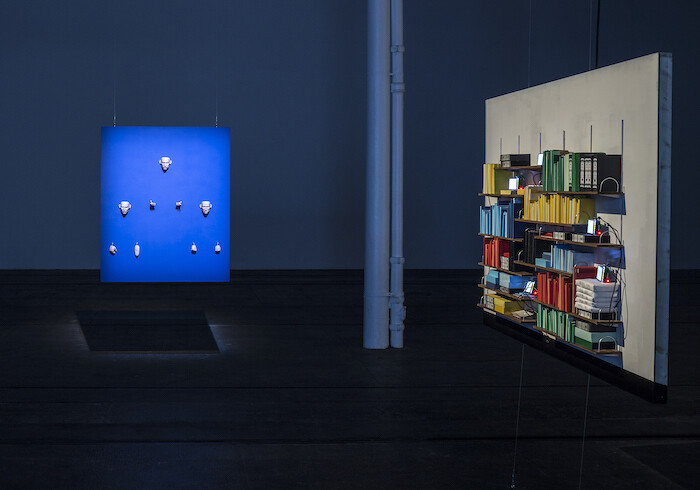

In the world of self-regarding architect Amos, there’s really only one thing that matters—Amos. There he is, sensibly chic in a black roll-neck sweater and neat gray trousers: “I want to build something important. I want to change the world. I want to express myself.” Amos is Cécile B. Evans’s amalgam of the twentieth-century starchitects who shaped the post-war built environment. Conceived as a mock TV series set in a Brutalist housing estate, her exhibition at Glasgow’s Tramway comprises three separate videos (or “episodes”). Made between 2017 and 2018 and collectively titled “Amos’ World,” each is screened concurrently in accompanying installations with soundtracks played on headphones. Dotted around the space are props and sets used on screen: scale-model shelves of colored binders, a miniature forest. As “Amos’ World” suggests, the egoistic visionaries Amos parodies were not ultimately in control of their designs. Evans emphasizes this point by rendering Amos as a jerky puppet.

Recent decades have seen the tearing down or repurposing of many of these architects’ buildings. Yet, Evans suggests, Amos has a far more influential contemporary equivalent in today’s social media monopolies and search engine monoliths—data architects whose mission is to “organize the world’s information” and “bring us all closer together.” “Amos’ World,” however, is about more than the foibles of a man incapable of imagining a world without him in it. The narrative that arcs across the three 25-minute episodes places viewers in a “socially progressive housing estate” that quickly alienates its undeserving (in Amos’s view) inhabitants. But “Amos’ World” is not a didactic unpicking of modernist thinking and aesthetics. Instead, the exhibition acts as an allegory for a recurring concern in Evans’s work: “how digital technology impacts the human condition.”1 Evans’s videos to date have predominantly consisted of digitally rendered characters adrift in click-through worlds: the future-gazing information overload of What the Heart Wants (2016), for example, or the CGI copy of “a recently deceased actor called PHIL” in Hyperlinks or It Didn’t Happen (2014). “Amos’ World” sees Evans working with actors, adding warmth and humanity to her complex, ambitious practice. It’s a development that creates a deeper feeling of engagement with the work.

Reality and fantasy merge across “Amos’ World.” Viewers are introduced to a cast that includes, amongst others, The Weather (a disembodied voice that questions Amos’s motives); Gloria, an actress whose dead mother is represented first by a blue animated swallow and later by a swirling blue mist; and The Secretary, a reference to the real-life secretary of AI pioneer Joseph Weizenbaum (1923–2008), who asked him to leave the room while she conversed with ELIZA, a chatbot designed to mimic a psychotherapist.2 In keeping with Evans’s interest in the value placed on emotions in contemporary, digitally mediated society, the mood throughout the videos is marked by shifts in emotional energy. There are lingering tears; surging swathes of evocative synth music; and the Nargis, a trio of animated teenage flowers who leave The Secretary’s flat to join a terrorist organization “comprised of entities let down by buildings.”

Evans pays close attention to how people experience her work, and “Amos’ World” creates a fittingly enveloping environment in which to play out this tale of individual hubris brought to heel by collective resistance, of lost souls finding networked ways to turn solitary grievances into communal action. Two austere concrete-gray architectural structures resembling stairways in Brutalist buildings sit at either end of the gallery. Viewers have to enter these “buildings” to view the first two episodes, climbing the stairs and sitting on cushions in one of several tiny, dark spaces. The cocooning effect of the space itself, combined with the use of headphones, creates an intimacy that resembles individualized, screen-based experiences of the internet. For the third film, the format changes: the characters are brought together for an episode filmed in front of a live audience. This shift is reflected in how it is viewed—out in the open, projected on a large screen in front of which are Erratics 1-X (2018), a series of concrete seats that resemble large pieces of rubble from a collapsed building. There’s a new openness on screen, too, as connections are made between the characters. Even Amos appears to accept that his ideas are flawed.

The final scenes of “Amos’ World” strike a hopeful note as the synth music swells and moods are lifted. One character states “We all have the capacity to represent ourselves”; another that “even when things are bad there is the possibility that things will get better.” The building, its inhabitants suggest, may have failed, but that doesn’t mean it’s a failure; it can be put to a new, better purpose if those living in it are empowered to shape its use. The same applies, Evans suggests, to our relationship to digital technologies. To paraphrase Gloria in the first of the videos, “maybe hope is the best kind of resistance we have.”

Cécile B. Evans interviewed by Roxanne Bagheshirin Lærkesen, February 2016, http://channel.louisiana.dk/video/cecile-b-evans-virtual-real.

Interview with Joseph Weizenbaum, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RMK9AphfLco.