“Man has no power of altering the absolute conditions of life; he cannot change the climate of any country […] It is an error to speak of man ‘tampering with nature’ and causing variability.”1 Charles Darwin wrote those words in 1868, nine years after the publication of On the Origin of Species. His view that human action has no lasting impact on nature remains widespread. It has underpinned disagreements among the geological community in determining whether or not humanity’s impact on the planet warrants its own named era: the Anthropocene. The conception of the Earth as a fragile system threatened by the actions of its human occupants, actions which could lead to adverse consequences on geological timescales, is relatively recent.

Given the steep rise in social and political attentiveness to climate change in recent years, it is hardly surprising that cultural institutions have followed suit. In 2019, a number of major exhibitions around the world have focused on nature and climate: “Broken Nature” at the Milan Triennale, Nature—Cooper Hewitt Design Triennial in New York, and the travelling exhibition “Nature’s Nation: American Art and Environment” that opened at Princeton University Art Museum. London’s Tate Modern has tried to pass off the sensory spectacle of Olafur Eliasson’s exhibition “In Real Life” as being partly about climate change. The proliferation of such shows means that one can feel wary about the sincerity of intent. Is there a genuine interest in meaningful engagement and critique (including institutional self-criticism) or a calculating attempt to piggyback on existing media attention?

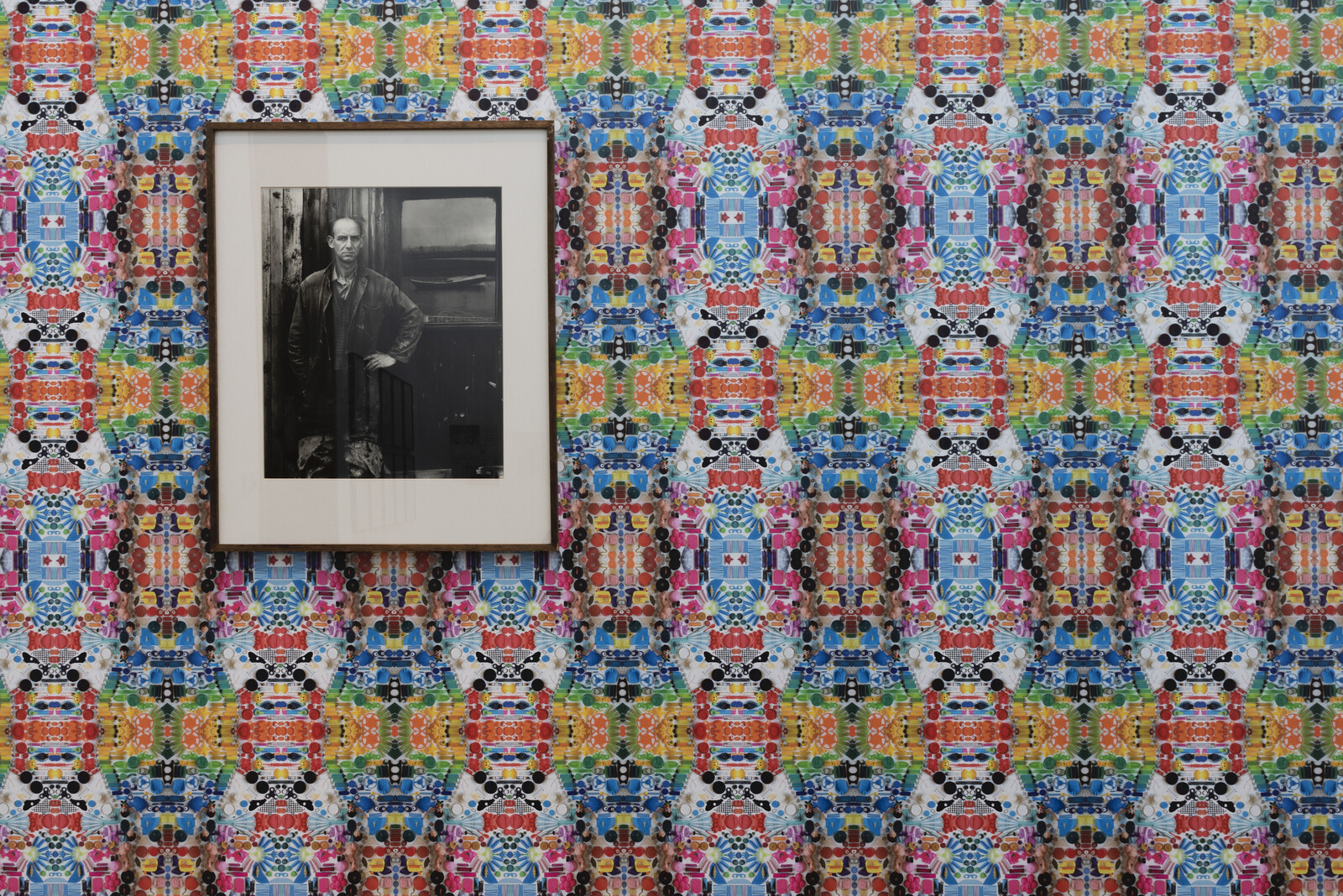

Rather than make sweeping proclamations about art’s power to address the problems of climate change, “Fragile Earth,” the summer exhibition at Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (MIMA), aims to demonstrate how a certain group of artists can help people connect with and understand the scale of the crisis. Although many of the exhibition’s most impactful works will be familiar to some visitors—notably Allan Sekula and Noël Burch’s The Forgotten Space (2010), a documentary about global supply chains, or The Oologists’ Record (2017/19), Andy Holden’s video about the harmful practices of obsessive egg collecting—certain of the newly commissioned works are particularly affective. Faiza Ahmad Khan and Hanna Rullman’s short video Habitat 2190 (2019), for example, deploys a remarkably light touch in its examination of the transformation of the Calais “Jungle,” the refugee and migrant camp that was forcibly cleared in 2016, into a nature reserve. Adopting a style that feels like a cross between a nature documentary and a twitcher’s home video, the work questions why certain societies find it easier to protect and provide homes for rare plants and birds than thousands of displaced humans.

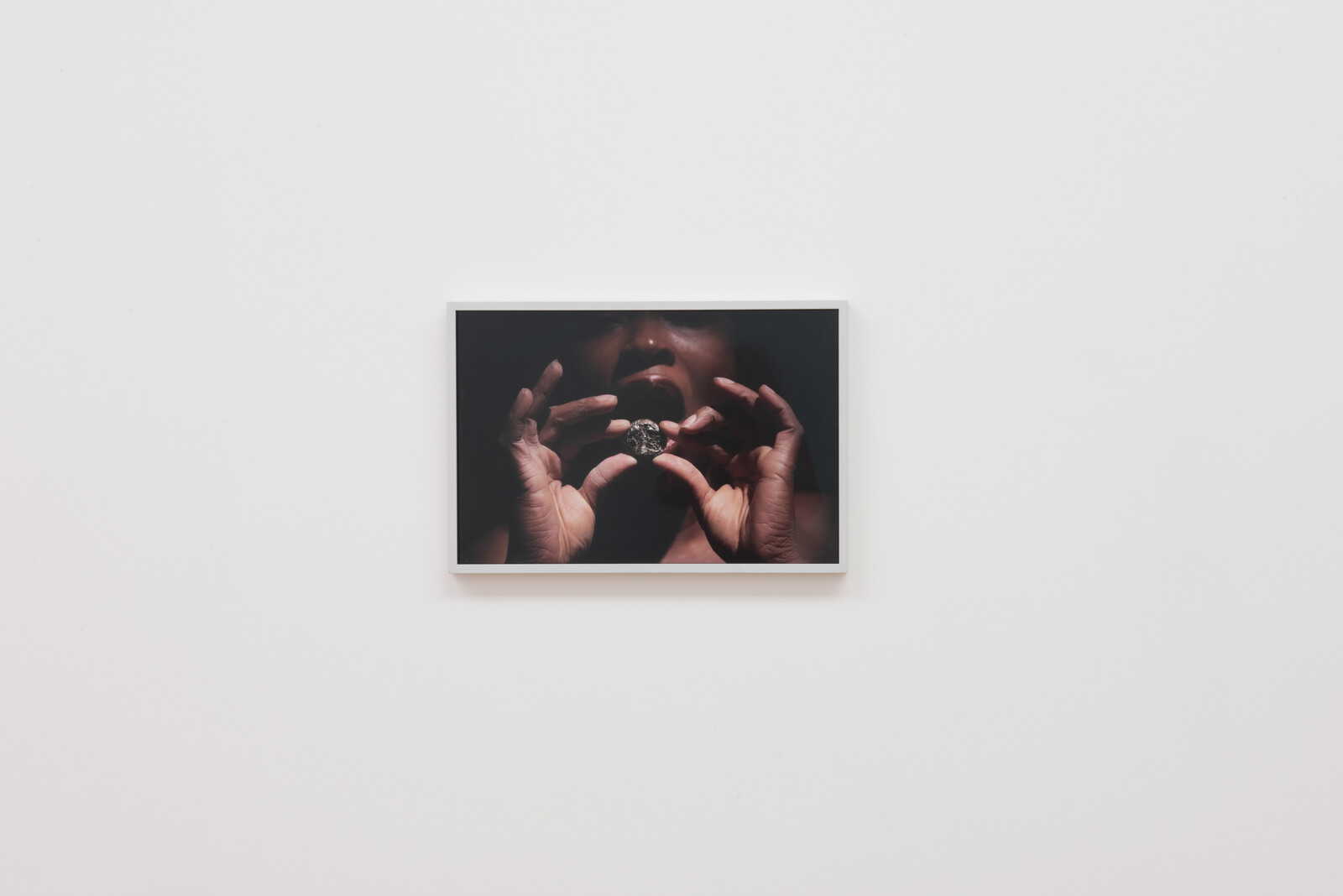

Disappearing places and people thread through a number of works. Anne Vibeke Mou’s delicate group of glass sculptures, A story of its own telling (2018/10), sit atop a low circular plinth. Made during a residency at the Corning Museum of Glass in New York state, Mou crafted the glass using traces of crushed fossils from the Gilboa Fossil Forest in Upstate New York. In so doing, she reminds visitors that—as has been painfully evident from recent forest fires in the Amazon—Earth’s great forests are as liable to rapid destruction as fragile glassware. Yet another video, Zina Saro-Wiwa’s five-channel Karikpo Pipeline (2015), offers a striking comment on colonial resource exploitation and the re-appropriation of abandoned infrastructure in Africa. Wearing antelope masks, Ogoni men from the Niger Delta region perform acrobatic movements over and across the remnants of exposed pipelines and old wellheads—a symbolic act of resistance and a ritual imagining of new futures for the exploited land.

Curator Elinor Morgan has adopted a strategy that privileges quiet impact and thoughtful reflection over shock tactics. As a result, the exhibition is neither bombastic nor apocalyptic. It doesn’t seek to shame or guilt visitors. Instead, they are encouraged to contemplate the difficult, often deeply contradictory character of humanity’s relationship with nature, and with itself. Considering the planetary scale of the exhibition’s subject, it’s also worth emphasizing Morgan’s attentiveness to diversity and gender balance in her choice of artists. Of the 19 exhibiting artists, more than half are women and around a third are from non-western backgrounds. “Fragile Earth” therefore provides a welcome example of how to make a meaningful, thoughtful, and deeply humane exhibition about the complex and emotionally charged issue of climate change in the twenty-first century.

Charles Darwin, The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 2.

%202017-2018'.jpg,1600)