Katinka Bock compares works to words and exhibitions to texts.1 The analogy explains the relationship between the two aspects of the Franco-German artist’s work: the sculptures, silver prints, and occasional films, on the one hand, and the sophisticated displays that she creates out of them, whose value is greater than the sum of their parts, on the other. These correspond to two ways of reading Bock’s practice: to focus on the single work, with its delicate material qualities, or to embrace the whole, with its syntactic properties.

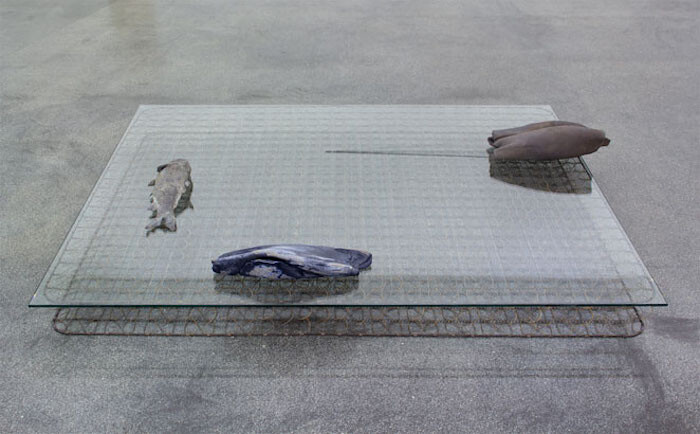

If Bock’s exhibitions are texts then “Smog,” her third solo show at Berlin’s Meyer Riegger, is particularly poetic. Two rooms are arranged as if they were two long sentences, rich in subordinate clauses and parentheses; sentences that could have been written by Marcel Proust, full of internal symmetries, of repetitions and variations, aimed at pursuing a nuance of perception or memory. The first room revolves around Grosse Liegende (2017), which is made out of several elements: a horizontal support (an old mattress coil topped by a glass pane), upon which the artist has placed the metal mold of a fish, a matte brown ceramic sculpture, and another ceramic sculpture with abraded blue enamel. The spectator perceives, in a fluid transition that renders the distinction between figurative and abstract superfluous, three variations on the same tapered and organic form.

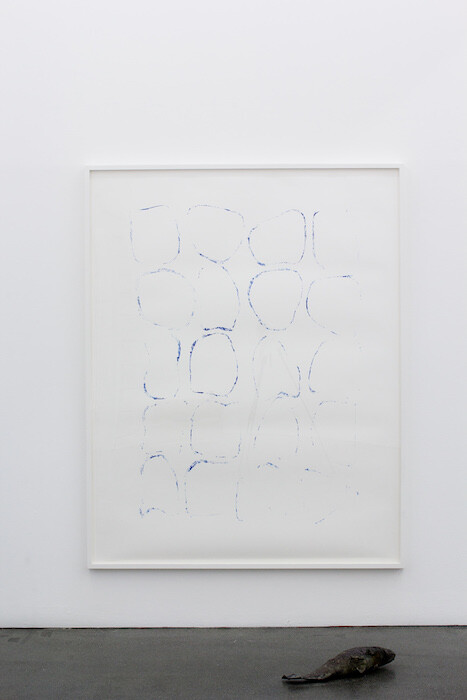

Around Grosse Liegende a series of subtle references is orchestrated. The large monotype of April Sculpture (big blue print) (2016), printed using the ceramic cylinders of a sculpture made last year, echoes La part de l’autre (2017), a sculpture composed of two similarly rounded elements. This, in turn, extends into Throat (N and S) (2017), two photographic studies of the neck as cylindrical connection and support.

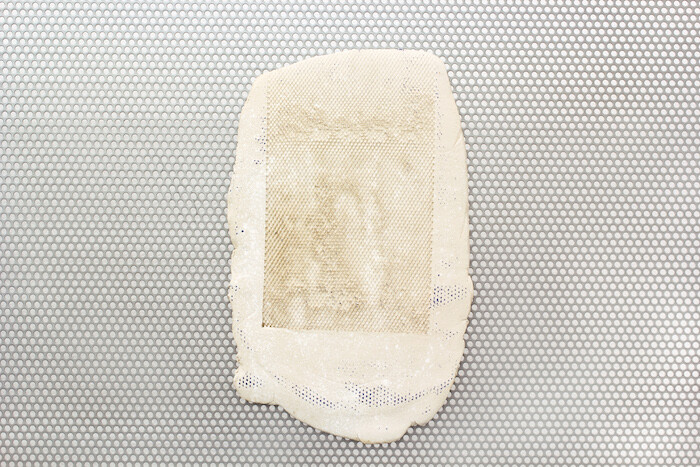

The second room has a simpler structure. It is based on a clear spatial and perceptual counterpoint: on the floor, a small group of sculptures, two of which (Smog I and Smog II, both 2017) are bronze casts of a cactus whose “smog colored” patina gives the show its title; hanging parallel to the wall, a series of perforated metal sheet rectangles on which the artist exhibits small ceramic and bronze sculptures. Conceived as exhibition props and arranged at different heights and depths, the rectangles evoke the dimensions of painting. They enhance the perception of the small sculptures as images, whereas the standing sculptures are experienced in the round.

Over the past decade Bock has established a repertoire of materials (chief among them ceramic), forms, and textures. If the exhibition is a text and the works are words, we could compare these constituent parts to syllables, defined by their quantity, sound, and combination. This level reveals the most personal of the artist’s traits: her attraction to certain textures, such as the imprint of the cloth that wraps the clay, which ceramists usually eliminate but Bock often keeps; her fondness for the sculptural gesture of folding, or delicately crumpling, a sheet of malleable material; her recurring fascination with water. This is sometimes explicit—as in Parasite Fountain (2017), the working fountain exhibited by Meyer Riegger in collaboration with Galerie Jocelyn Wolff at this year’s Art Basel—and sometimes implicit—as in the metallic cast of a fish in Grosse Liegende and the blue-and-white ceramic placed close to it, evoking the stream in which the fish once swam.

From these predilections a rich range of sensitive effects opens up, stemming from the place where look meets touch; the point in which the two senses cooperate in grasping the form, the grain, the weight of an object. It is by way of these effects that Bock’s works challenge the exclusive privilege granted by our digital era to the faculty of vision. They serve to re-educate our atrophied sensorium, reacquainting our complex and complementary senses with the nuances erased by the smooth surfaces of our touchscreens.

Phone conversation with the author, October 2017.