Dineo Seshee Bopape’s installation Sedibeng, it comes with the rain (2016), the one work on show in her exhibition at Eastbourne’s Towner Art Gallery, darts between person and place before gesturing upward. Sedibeng, a Sesotho word meaning “the place of the pool,” can be a person’s given name and is the name of a district in the Gauteng province of South Africa. The work’s title is an apt introduction to Bopape’s approach to material associations, which, through a process of collage, allows references to complicate, fracture, and loop back on themselves. There are many avenues through this work, all contingent upon the vantage point from which the viewer enters. Knowing where to begin is tricky, but it is also the joy of navigating the puzzle.

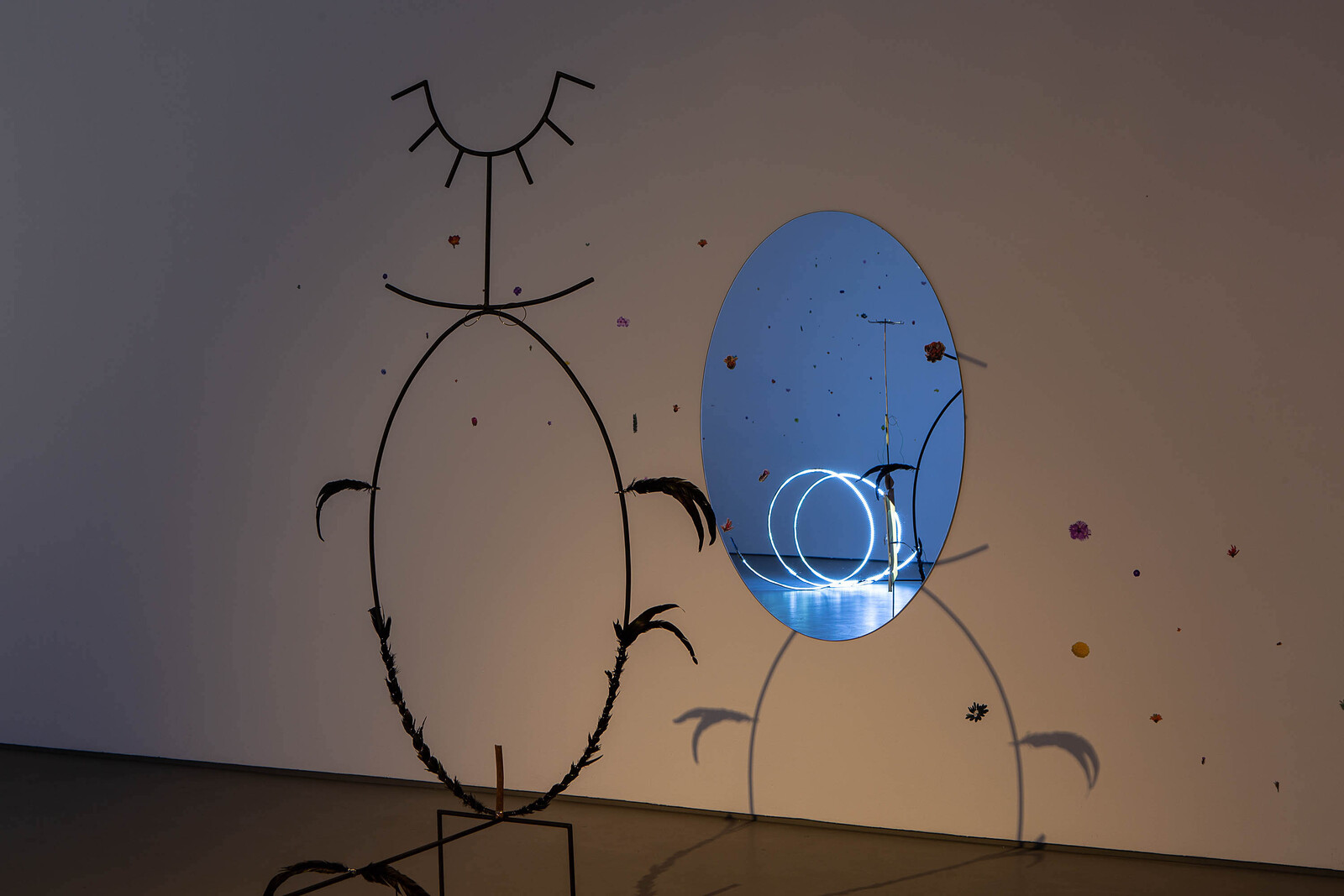

Six sculptures made from steel bars are adorned with crow’s feathers, medicinal herbs, spices, cut-out photographs of flowers and fruit, charm jewelry, bent copper wire, and green potters’ foam. The sculptures incorporate simple, geometric shapes such as ovals and triangles, amalgamating abstracted spiritual symbols drawn from cultures across the world. No information about these sources or materials is provided. As a result, understanding this exhibition can be a daunting challenge. Navigating the periphery of the installation, I was reminded of artists such as Laure Prouvost, Samara Scott, and Helen Marten, who collate found objects to forge ambiguous material lexicons. But while they draw upon the visual and material languages of western popular and consumer culture, Bopape references esoterism, spiritualism, and the African diaspora. The largest steel sculpture contains symbols that reference the sun and the moon alongside masculine and feminine motifs—an inverted pyramid, for example, doubles as a vulva. Considered in relation to the artist’s inclusion of herbs used to aid fertility, these suggest a cyclical model of birth and life.

The darkened installation is punctuated by bursts of light emitted from overhead projectors placed on the floor. Star anise are scattered on their surfaces, their shadows cast upon the walls and across the ceiling. Soil—a significant material in Bopape’s work—features in a slideshow of images projected on a piece of cardboard at the center of the installation, showing close-up snapshots of a hand molding dirt and clay. Earth, in this instance, doubles as a reference to burial and the colonial removal of land. The crow feathers heighten the mournful, contemplative atmosphere established by the installation’s dim light. In world lore and literature, crows can symbolize ill health and loss—omens of death—or be celebrated figures denoting transformation, rather than life’s end. That both interpretations are possible testifies to the complexity of Bopape’s imaginary. What may initially register as hopeful and transitory, freedom and flight, can switch to mourning or loss. The artist purposefully leaves the densely packed associations—healing, nature, cosmology, moving through individual, collective, and global scales—open to interpretation.

Bopape disrupts her symbols and references but those that relate to gender can feel restrictive. And while the centrality of procreation to Sedibeng suggests that she is promoting sovereignty over one’s own body, I wondered if this could have been further complicated, so that a reading of femininity could extend beyond reproductive biology. Fertility, nonetheless, is a central element in the artist’s work, an anchor around which she positions wider elements, natural, planetary, and cosmic. Navigating them is a process of doing and undoing her assiduous compositions that refuse easy categorization.