For Sondra Perry’s solo exhibition at Bridget Donahue, New York, all the walls are painted Rosco Chroma Key Blue. The deeply saturated color is used on television sets and in the production of special effects for movies and videogames because it contrasts so profoundly with most human skin colors. Chroma Key Blue is the obverse of the color of being, Sondra Perry pointed out to me at the opening. No human skin exists in an adjacent shade, and so it can be used as the negative space onto which context for any body can be manufactured and projected. The color of ultimate negativity, or the absence of existence.

Perry’s interest in the condition of visibility is influenced in part by Simone Browne’s Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness (2015), which analyzes the way people of color are visualized using surveillance technologies and, through this visualization, de-humanized.1 Browne traces the containment of blackness from basic technologies, such as branding and lantern laws, to more technically advanced forms used in contemporary policing.

Black bodies are often represented in the aforementioned visualization techniques against a ground very similar to Rosco Chroma Key Blue: one of the conditions of their visibility since slavery has been that they can be infinitely removed from their own narrative, and infinitely available for the historical demands of white hegemonic discourse. Perry’s recursive use of Chroma Key colors in the broader body of her work is a reminder that technologies of containment are composed of sometimes very simply rendered binary distinctions between the body and its contextualizing narrative, or the lack thereof.

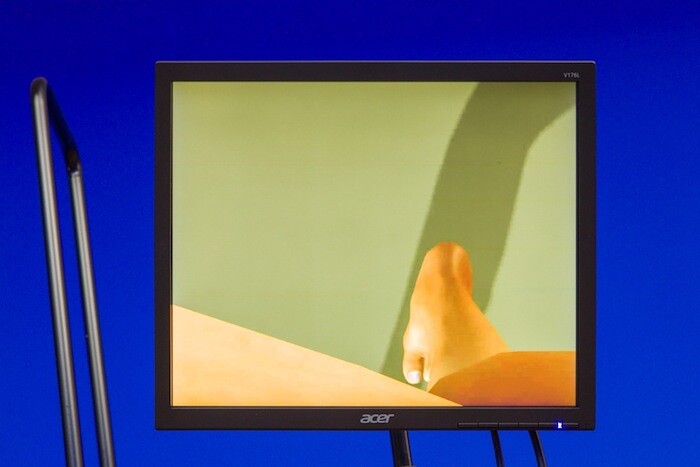

Set against the blue non-space are modular black metal frames of human size and girth that Perry calls “workstations.” The frames are made from athletic equipment, the function of which is to model defensive players during basketball practice. The forms are typically configured to have their “arms” out wide or up high to help train players to dodge and weave, like semiotic “enemies.” Perry has positioned the limbs of these figures idiosyncratically and equipped each with a monitor partially masked from view with a privacy screen. On each screen, she has rendered a different fragmented view of a body in 3D, creating the impression that the frames are possessed of an uncanny interiority. They have abandoned their role as the hostile props in someone else’s game. They have gone rogue against an infinite digital landscape.

On a large screen that hangs at an angle in the far corner of the gallery—like the scoreboard at a sports event—Perry draws four distinct genealogies of representation together through the video IT’S IN THE GAME ‘17 or Mirror Gag for Vitrine and Projection (2017). A sequence of out-of-focus family snapshots of herself and her twin Sandy as happy children in the rich red and brown color palette of the 1980s serves as background to spinning, homeless figurines rendered in the ubiquitous Chroma Key Blue; they are silhouettes of cultural artifacts from the exhibits on Africa, Oceania, and the Americas at the Metropolitan Museum in New York and the British Museum in London. Here the figure, not the ground, is fantasized as malleable.

There is also footage of the siblings at each museum looking at the artifacts in person as an impossibly cheerful voice gives a rendition of meaning and provenance for each thing. There is a shot of the flat space of a gray spatialization software program that allows users to plot video footage as 3D planes. But the conceptual center of the video is an image of the digital locker room and basketball court of a video game produced by EA Sports using data acquired from the NCAA (National Collegiate Athletic Association) accompanied by a video feed of Sandy Perry narrating the lives of each player whose statistics he recognizes tucked into one corner of the frame.

Sandy played college basketball on a scholarship. His likeness and vital statistics—even his own name—were used to create a videogame avatar. Neither he nor the other athletes featured in the game were consulted or remunerated, even though EA Sports paid the NCAA for their physical data, a transgression for which the players sued the NCAA in response and received a settlement. Sandy is shown scrolling through the videogame menu in which he appears and, at Perry’s request, fleshes out the people these statistics are meant to represent. “This one was a great guy, on and off the court.” “This other one was Polish and there was a lot of conflict between them”—Sandy utters subtle affirmations of the humanity of the digitally rendered athletes rotating slowly on screen in a simulated locker room.

The point seems straightforward: her brother’s body and those of his college teammates are decontextualized before being rendered as props in space of display, a space that Perry suggests is analogous to the universal gray space of the rendering software, or the totalizing and progressive logic of “universal” institutions like the Met and the British Museum. All four pretend to represent the infinite dimension of the human being from an institutional or algorithmic perspective, and yet each is riven with ideological violence, especially in their assumed prerogative to decontextualize black and brown life without consent or negotiated justification.

Perry is working against a very long material history of objectification. Yet what is striking in the video, as in the workstations, is the degree to which a trace of being remains lodged in the decontextualized things she renders. There is enough information in the EA Sports videogame rendering of his colleagues that Sandy can recount the outlines of the lives they were abstracted from. When Sandy and Sondra Perry are in the Met in front of the Dendur Temple they can still feel that there is something deeply violent about its dislocation. A trace of that which is uncontainable about human beings persists, even in the negative space of that intense, opaque blue.

Dean Daderko, “Conversations: III Suns: Arthur Jafa and Sondra Perry,” Mousse, No. 57, February/ March 2017.