Memory, noted Marguerite Duras, is an attempt to escape the “horror of forgetting.” It is also, she argued, a failure: “You know you’ve forgotten, that’s what memory is.”1 The memory of the things we forget we call the unconscious. A group show at Tel Aviv’s Dvir Gallery, conceived in homage to Gustav Metzger and featuring works by Armando Andrade Tudela and Daniel Steegmann Mangrané alongside the late artist, traces the ways in which amnesia and memory constitute each other in the writing down of history.

At the center of “Lacrimae Rerum,” a lavish yellow fabric covers a large black-and-white photograph fixed to the industrial floor. This photograph from March 1938, part of Gustav Metzger’s “Historic Photographs” cycle and titled To Crawl Into - Anschluss, Vienna, March 1938 (1996–2020), has been enlarged to about thirteen square meters. It shows Jewish citizens in Vienna who were forced to clean the streets of the Austrian capital while Nazis and fellow citizens watched on, shortly after the Anschluss. In order to see this larger-than-life photograph, the viewer is required to crawl on all fours under the cloth, moving along the image’s surface, too close to comprehend it as a whole. The yellow fabric (as a screen or a theatrical curtain) compels the viewer to repeat the humiliating act. It also deprives them of the distance, control, and stability that the vertical viewing posture conveys; in fact, of the very notion of “viewer.”

Metzger used perplexity to approach history—specifically the events of the Holocaust, which were central to the artist’s life and work—with its own mechanism of concealment. Two more works from his “Historic Photographs” cycle were recently shown, alongside works by Miroslaw Balka, Marianne Berenhaut, and Latifa Echakhch, at Dvir Gallery’s Brussels space in the first part of this exhibition-homage. There, two well-known historic images—Hitler-Youth, Eingeschweisst (1997–2020) and Liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto, April 19-28 days, 1943 (1995–2020)—were obscured, enveloped between two metal sheets, or made inaccessible with a barricading pile of rubble.

In The Edge of a Hole is the Back of a Cave (2020) by Armando Andrade Tudela, shown in Tel Aviv, the space (or event) and its record or scheme are materialized through the correlation of fabric geometrical abstractions—each almost three meters high and hanging on the walls like mysterious banners—to a series of black-and white photographs, capturing a deserted construction site in a process of decline. Elsewhere, a group of Metzger’s early abstract drawings from 1953, which feature expressive marks in black, gray, and pink pastel and graphite, underscores the paradox of his particular art-making, which aims towards the destruction of the artwork.

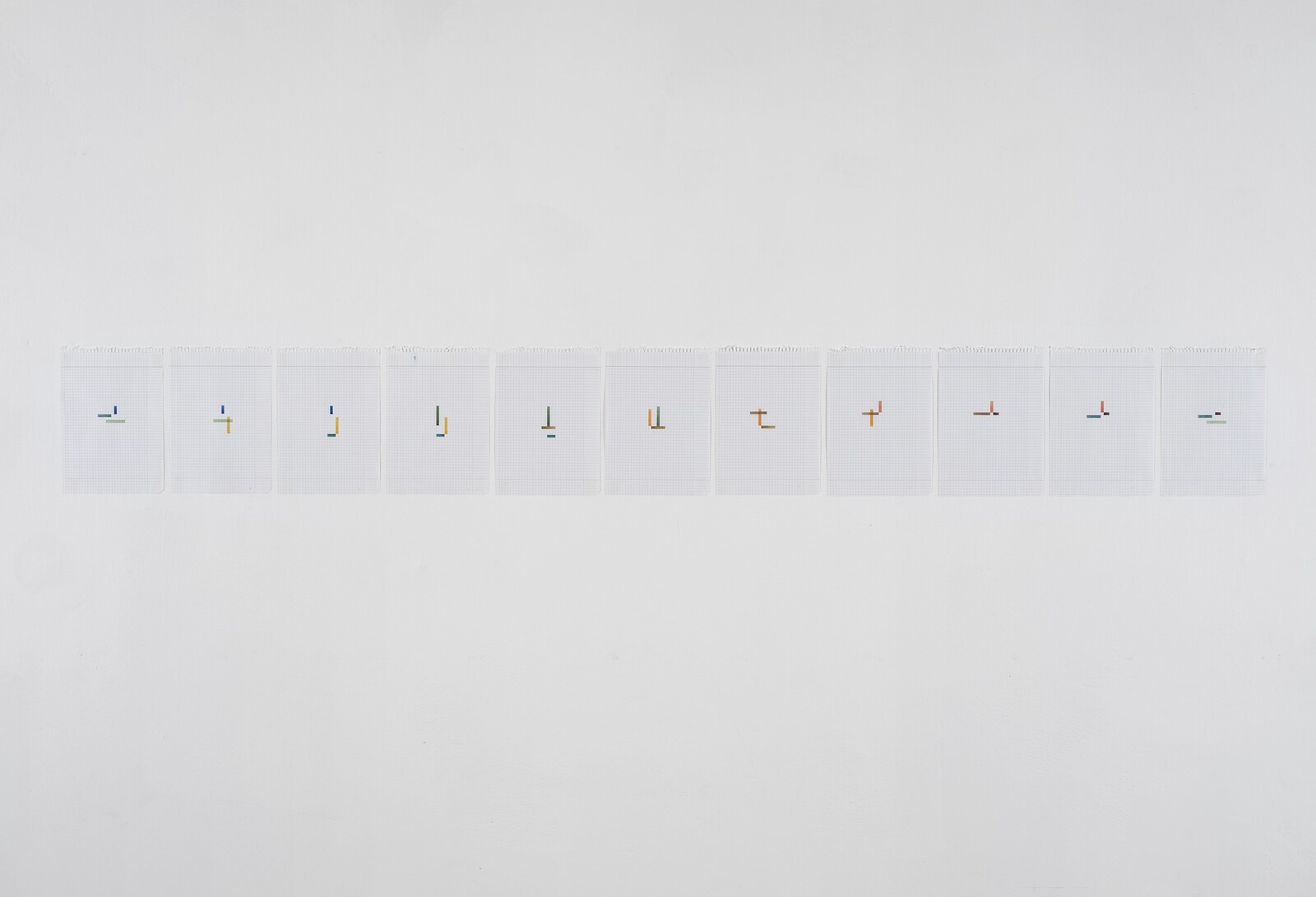

Daniel Steegmann Mangrané’s series of fine geometrical watercolors on eleven A4 sheets of graph paper—diagrammatic combinations of red, yellow, green, and blue bars—hang in a row on one wall. The title of this series, Lichtzwang, is borrowed from the title of Paul Celan’s last collection of poems, written in 1967 and published in 1970, three months after the poet’s death. Lichtzwang, a compound noun of Celan’s invention that pairs the German words for “light” and “compulsion” or “pressure,” appears in one of the book’s short poems, “Wir Lagen” [We were lying]. The poem describes a figure crawling into scrubland, which brings forth a collision, even a struggle, between two movements: one towards darkness, and another—the one that reigns—towards light. “[Y]ou crept up at last. / But we could not / darken over to you: / light compulsion / reigned.”2 Yet since light and darkness are exceedingly dualistic, their meanings here can be inverted. Whereas the unreached darkness may offer (also) shelter, the light is (also) a coercive force.

Another work by Steegmann Mangrané echoes the reversal of power in Celan’s words. Each pair of bare wooden beams of varying lengths in a series of untitled floor sculptures from 2020—their placement continuous with the act of crouching in Metzger’s floor piece—is separated by a delicate grass weed. It seems that a movement of the raw, heavy logs toward each other is halted by a flimsy plant, radiating incredible strength despite its appearance (indeed, the geometrical shapes in Lichtzwang recall logs).

Kneeling, crouching, and crawling physically connect the different parts of this emotionally resonant exhibition, reflecting gallerist-curator Dvir Intrator’s sensitive reading of Metzger’s heritage. Crawling—in Celan’s poem and in Metzger’s artwork—is a way of seeing. It is an attempt to approach something inaccessible by actively forgetting its (traumatic) memory.

Suzanne Lamy and André Roy, Marguerite Duras à Montréal (Paris: Éditions Spirale, 1981).

Paul Celan, Poems, trans. Michael Hamburger (New York: Persea, 1980). German original: “Wir lagen / schon tief in der Macchia, als du / endlich herankrochst. / Doch konnten wir nicht / hinüberdunkeln zu dir, / es herrschte Lichtzwang.”