September 17–December 9, 2018

As of this writing in mid-November, “American MONUMENT” by lauren woods has been “paused” (not withdrawn) by the artist. It is a gesture meant to protest the firing of Kimberli Meyer, director of the University Art Museum at California State University in Long Beach and an instrumental collaborator in woods’s project, only days before the show opened. The 25 turntables on white plinths still stand at attention, formed into a grid in the gallery’s center. Under other circumstances, however, these would have borne 25 vinyl records which, when the viewer lowered the needle, would have played audio related to the last moments in the lives of 25 black Americans killed by the police: body cam recordings, smartphone streams, documents read by actors, and audio from court. A set of 25 metal boxes on metal tables and shelves would have contained facsimile case materials related to each slaying.

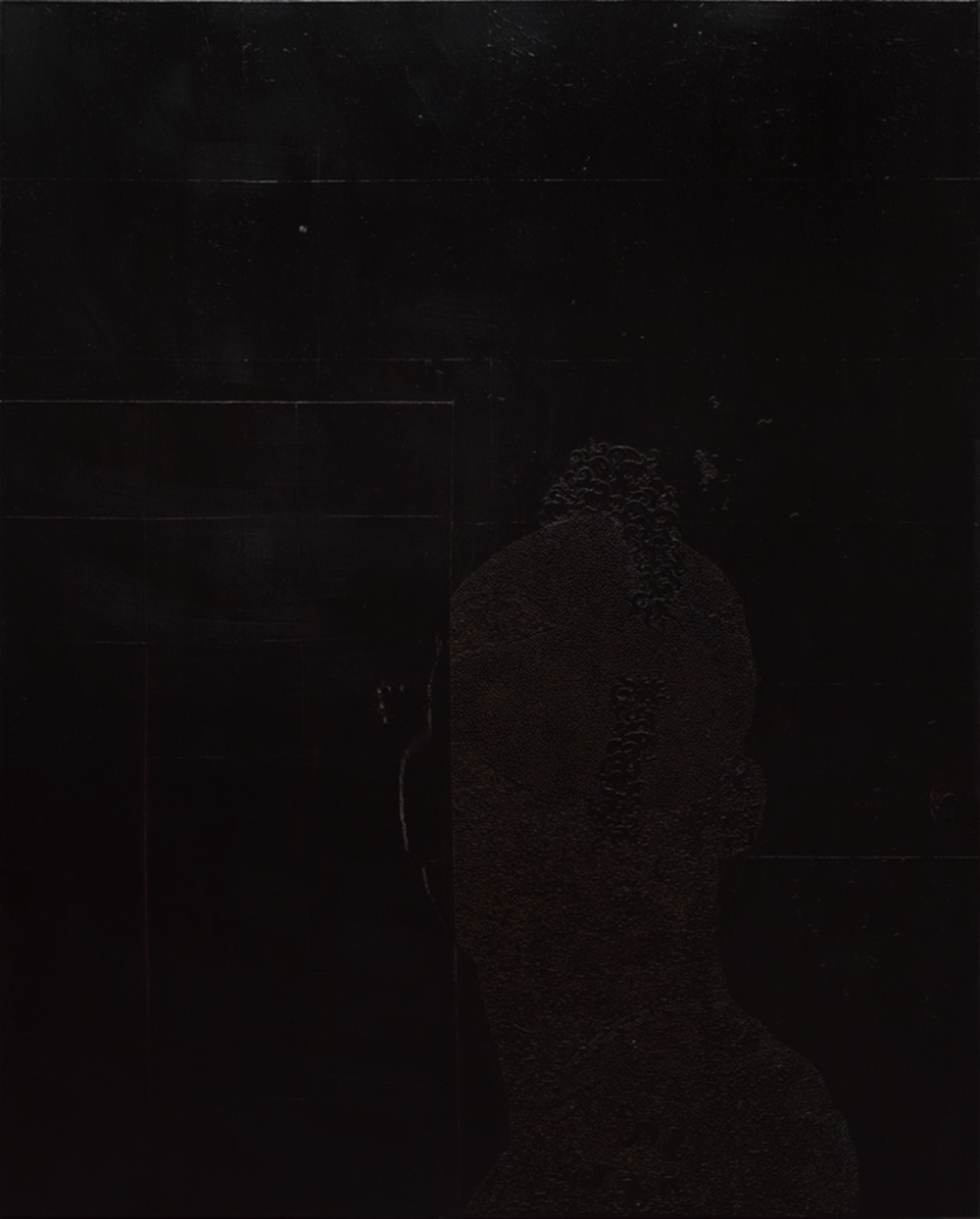

It was always going to be an austere, formal show. Now it’s assuredly formalist. The boxes, open on the table or closed and put away on shelves, are uniformly sized, and uniformly empty, like the plucked lobes of a Donald Judd stack. The plinths, too, are identical, and recall the stelae of Berlin’s Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe. The bare turntables they currently support are all Pro-Ject Debut Carbon belt-driven models with factory cartridges, displayed without dust covers, ostensibly selected for their near-blank minimalist styling: the only text (and the only texture) appears on the tone arm. A few are noticeably off-center. They all face the same way. Seventeen are white, eight are black, and woods has arranged them by color into a square pattern. The grid of plinths and turntables is lit from above and set apart by a raw plywood platform roughly four inches high.

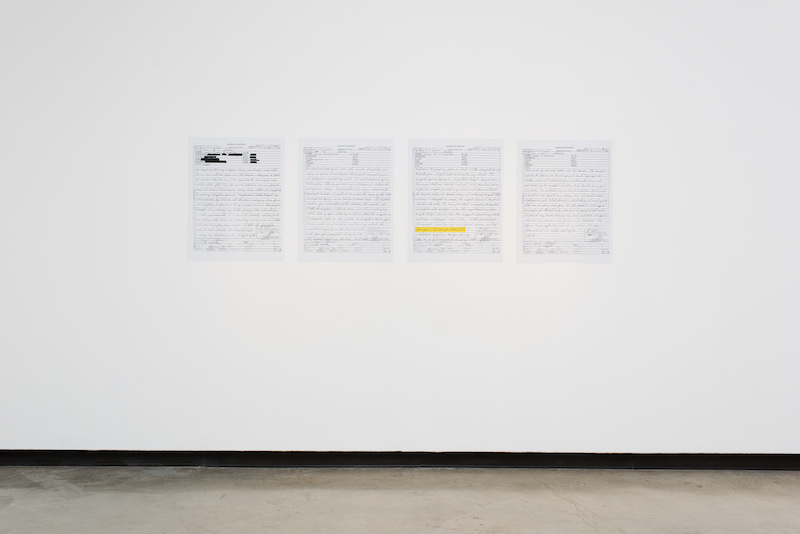

What isn’t there is inseparable from what is. The arranged plinths furnish the main room of the museum, while the tables and boxes and several wall works occupy the smaller side galleries: the decision to pause the exhibition does not include the three blown-up sets of documents related to three of the 25 killings, fixed to the peripheral walls. One room counterpoises two sizes of the medical examiner’s diagrams of the wounds that killed Laquan McDonald (“age 17 y, sex M, race B”). (The officer responsible was later convicted of second-degree murder and 16 counts of aggravated battery with a firearm—one charge per bullet.) One pair of drawings, back and front views of a white-looking adult male, is printed at document scale. Another pair appears life size on the opposite wall. In this room, woods keeps her show’s central conceit on view: the sickening tension between a victim’s evident humanity and their systemic dehumanization. The bullet wounds are labeled in a banal, nondescript hand. Two other upscaled sets of handwritten forms appear in two of the museum’s other corners. In one, the incident report related by George Zimmerman after he gunned down Trayvon Martin; in the other, a transcription of the grand jury testimony from the officer who shot and killed Michael Brown. In each, woods has highlighted a key phrase in yellow: “your gonna die tonight motherfucker,” in the former, and its inverse in the latter, “you are too much of a pussy to shoot me.” These are words put into the mouths of the slain by their killers after the fact of their deaths. Here, again, a sense of wrenching, unruly specificity—and lopsided injustice—cuts through the exhibition’s clean silence.

Likewise: entering through the adjacent campus study hall rather than from outdoors, the first thing visitors see is an open cabinet of receivers and wires where the horrific feeds from 25 stereo turntables would have mixed into a single discordant collage. Of course, these are turned off—as if there were any question that the present iteration of “American MONUMENT” is, above all, a visual experience of the sculptural qualities of audio equipment. The artist has heavily, politically redacted her own work, leaving just enough context to suggest what is withheld. What that context suggests is the tragic, familiar, and unspeakable cadence of black death spectacularized in the news. The MONUMENT, meanwhile, has taken up another rhythm: that of formal reification—that of a system that collects violent deaths, then abstracts them.