Blackness fills in space between matter, between object and subject, between bodies, between looking and being looked upon. It fills in the void and is the void.

—Nicole Fleetwood1At stake, finally, is emphatic, surreal, nonperformative presence in the making of a living: at stake is “the presence of flesh.”

—Fred Moten2Racial difference teaches us to see.

—Anne Anlin Cheng3

1.

I am looking at a video of a black man being beaten relentlessly by a figure he can neither see nor evade, and whom he can therefore never overcome. Up on a stage, his glistening muscular form jitters and folds under the juddering blows of this invisible adversary. He stumbles and rolls around a boxing ring, the rippled surface of his flesh made over into a telemetry of signs. Why do I watch him? Who does he face? How can he escape an enemy whose presence is no longer susceptible to proof, but whose actions are inscribed in his black flesh at high definition and rendered in slow motion, as the blows rain in, over and over and over again?

The video is a looped reel of edited digital footage from a boxing fight. Entitled Caryatid (Broner) (2020), it is part of a longer series the artist Paul Pfeiffer has been making since 2015. In each video, the opponent of a boxer named parenthetically in the title has been patiently erased from every frame of the footage. This careful pattern of erasures brings the black man’s body and its responses into high relief on the canvas of the ring. The erasures transform him from protagonist into recipient; they mold him into a continually recursive before-and-after-image of an incident whose occurrence we can confirm, but whose provenance we cannot identify.

Caryatid (Broner) departs starkly from the traditional physical form of Pfeiffer’s Caryatid works. Where these have historically been embedded in customized television sets staged like buoys on the sparse floors of galleries, the full series is now viewable as options in a dropdown menu on a website: the videos become fragmentary media objects appropriated from the web and now returned to it, spectrally, proleptically, in the midst of a general flood of digital images of antiblack violence. Caryatid (Broner) debuted in an online exhibition produced by the artist Sable Elyse Smith in late October 2020 entitled “FEAR TOUCH POLICE.”4 The site aggregates in fluid form a series of texts, images, songs, and videos that take up an explicitly abolitionist stance against policing, and that interrogate the structuring force of racist, classed, and gendered violence within American life. The project crystallized over the volatile summer of 2020 in which state acts of antiblack violence, and mobilizations against the same, reached a mass scale, both within the United States and globally.

The acronym for the exhibition (FTP) proliferated across the surfaces of urban and exurban space over the course of that long summer, its repetition unchained by the burning of the Third Precinct of the Minneapolis Police Department on the third night of the George Floyd rebellion. The colloquial translation (Fuck Tha Police) is a phrase that echoes the anthemic cry of hip-hop emcees uttered in defense of the very notion of black social life. Smith’s subversion of the acronym points up the recurrent and exonerating role played by police “fear” in the prosecution of lethal violence against unarmed black and brown people across the United States, and the conjunction of abolitionist politics with Pfeiffer’s Caryatid series echoes the gladiatorial nature of interactions between armed police and minority citizens across the United States.

In Caryatid (Broner) I am acutely, painfully, viscerally attuned to the immanence and intensity of violence ranged against Broner’s solitary figure. Indeed, I am interpellated into his position by the work, my limbs possessed by his actions, his taut anticipation, his bewildered acts of evasion transmuting into a fear I live alongside and with him. I’ve lapsed easily into the presumption that the protagonist of the piece (if not the “action”) is the black man, but what if his visibility is a sort of foil, or a trap? What if his blackness is forcibly enclosed within the visible, and the protagonist is the unseen figure, or better yet, the unmarked force that eludes capture and assaults him freely? What might it mean to be invested in the actions of the unseen figure, and to conceive of that mobile nothingness that rains blows down from an unmarked placelessness as the prime mover in this spectacular contest? Who are we watching when we watch this fight? What are we watching in this contest: a battle of self against other, black against white, presence against absence?

In an essay on the integral role that processes and acts of objectification play in the formation of a sense of self, Anne Anlin Cheng writes that “in addition to the euphoria of self-displacement, invisibility appears to afford all kinds of subjective realizations, from physical to moral actualization.”5 Through her nuanced reading of Roger Caillois, Cheng argues that acts of camouflage and mimicry, practices of self-erasure, not only produce meaningful pleasure, but work as “modes of sociability” in which “self-erasure and fulfilment fuse.”6 For Cheng, there is a generative cohesion accomplished in the process of eradicating the self, which requires the treatment of the body as malleable material—which requires the performative modulation of self into other, the substitution of there for here, you for me, it for I. Cheng argues that it is “through spectacularization that the self achieves invisibility, and it is through this paradox that the subject enjoys what Caillois proceeds to call the ‘strange privilege’ of presence.”7 We might look at Caryatid (Broner) as materializing this process of mimicry and erasure and consider it as bound up in what Cheng describes as “an act of disappearance through which a subject actively inserts him/herself into a social field.”8 In what ways do acts of self-erasure and self-determination traverse this spectacular scene?

Arguably, on this stage, a boxer like Adrien Broner defines himself as such in the processes of giving, evading, and receiving blows; he is thus constituted in and through violence, whether as fugitive from, subject to, or perpetrator of the act. He is constituted as an agent through practices of dissimulation in which his body weaves and feints to make himself not where he appears that he indeed will be. But whether in receipt of attack, or in the prosecution of violence, Broner’s black body is a site and sight for the pleasure of others. The sculpted musculature of his frame, the shimmering pinks and yellows of his trunks, the gleam of his skin all constitute the pleasure that he generates within the scene. He acquires agency as a screen onto which an audience might project its own desires, or through which it can prosthetically extend itself. His subjection to perpetual assault conditions his legible standing with the social field.

Pfeiffer’s video skips through disjunct registers of motion, the frames alternately unfolding in slow balletic grace, or juddering along at high, dyskinetic speed. In them, Broner frequently doubles over at the waist as air is forcibly expelled from his body, his frame becoming a concave echo of attack, his body listing and flailing. He seems so often on the verge, the sheer force of blows tipping him to the very edge of collapse, as though his black body were roiled ceaselessly by ocean tides. At other instants his frame is battened down, taut, swaying on a rail at high speed, swerving left and right, up and down, moving always out of reach. I have the sense, when watching, that the force that assails him seeks to write him out of existence: that he is faced with the threat of immolation at the behest of the crowd that surrounds him. I have the sense that those baying with pleasure at his every move wish to taste his blood.

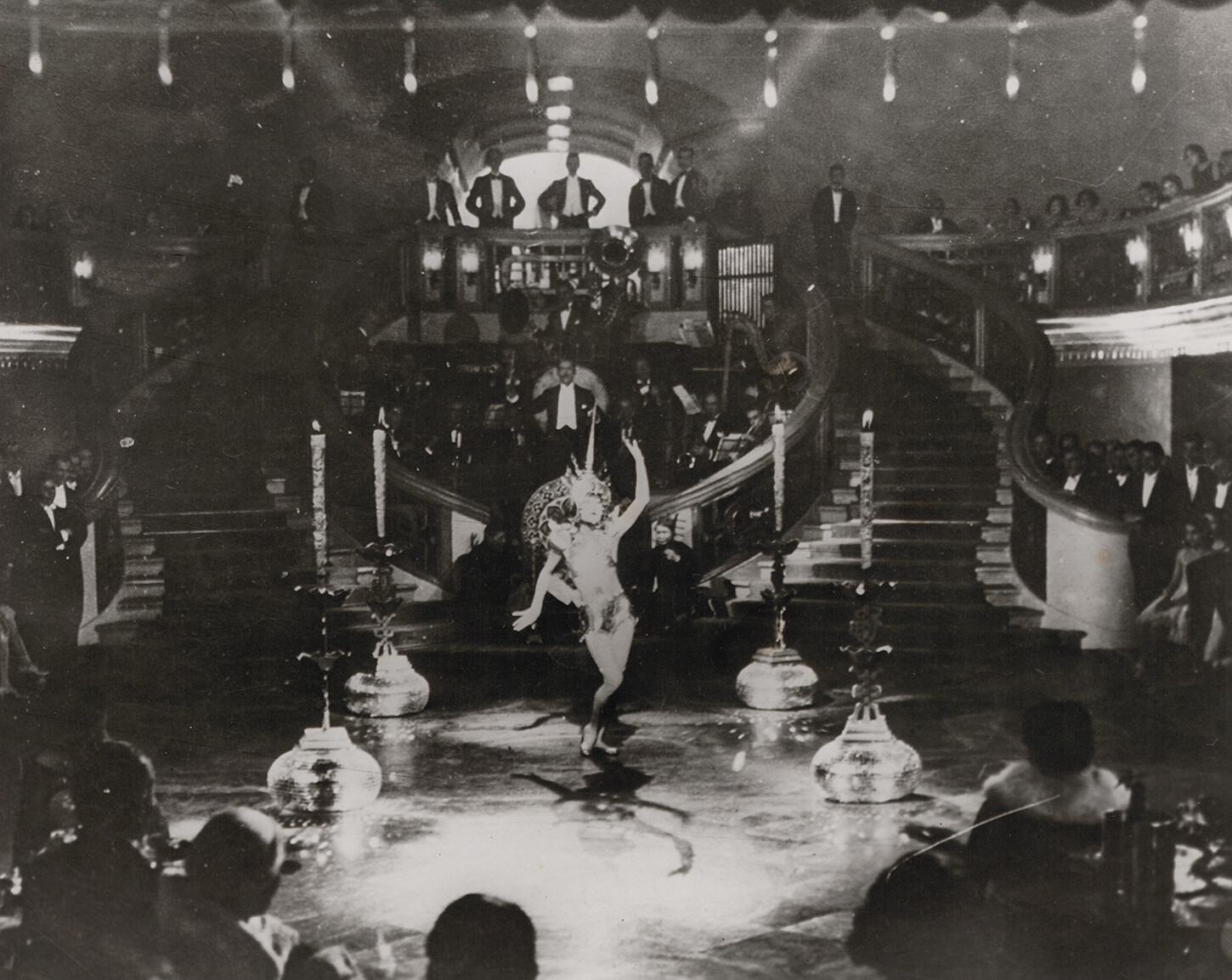

Film still from E. A. Dupont’s Piccadilly, 1929. Courtesy of British Film Institute.

2.

In her essay “Shine: On Race, Glamour and the Modern,” Cheng writes about the character Shosho, played by Anna May Wong in the 1929 film Piccadilly. Shosho is a dishwasher at a night club whose owner stumbles upon her in the basement scullery in the midst of an irreverent dance. He then calls upon her to dance on the club’s main stage, and her performance enthrals her audience, the club’s owner, and her own white female competitor for the spotlight. Cheng argues that Shosho’s bedazzling and seductive performance demonstrates how “fascination enables contact with objectness. It facilitates empathy for the imagined pleasure of self-objectification: the relished slide from me to it.”9 The evacuation of inner subjectivity from the person or figure by whom we are fascinated occasions a profoundly generative opportunity for the extension of the self through the “imagined pleasure of self-objectification.”

In the film, Shosho is clad in glistening, skimpy, metallic armor as she dances. Her recalcitrant withdrawal into this blank, brilliantly gleaming inaccessibility at once reiterates and reinscribes orientalist tropes of Asian reserve, and offers up the resplendent surfacedness of her figure as both screen and mirror. She becomes a screen onto and through which a white audience might project its varied fantasies, and a vibrant reflection of their inner need. Shosho, like the boxers in Caryatid, materializes the ways in which the theater of the spectacle and the drama of the image catalyze a massive intensification of the haptic experience of a fascination which seeks to possess the object that provokes it. This is to say that Shosho’s negotiation of spectacular visibility in fact visualizes the appetitive circuitry of racialized desire by which she is surrounded, and against which she orchestrates her gracefully evasive performance. Shosho figures a means of entering into visibility that mirrors back the complex investments that constitute visibility’s gravitational force, at the center of which the braided threads of gender and race pulse and intersect with uncontainable volatility.

The artist Deana Lawson accomplishes a similarly complex process of mirroring, creating images set firmly within the registers of spectacular appearance in which both racialization and the differential force of gender play a foundational role. Her luminscent photographic scenes subtly stage black performance, as it bears on the social life of blackness, within a visual regime suffused by the violent forces of racial differentiation. Through a series of artful—and, for most viewers, illegible—maneuvers of the view camera, Lawson often creates scenes in which the flat parallel planes of interior floors and surfaces slope downward diagonally toward the photograph’s lower frame line, rendering the center of her pictures into theatrical prosceniums atop which her subjects sit, lay, or stand. These subtle modulations of relationships between the lens plane and the film plane of view cameras have the effect of reconstructing the spatial arrangement of the interior spaces in which Lawson so frequently works. She enacts such compositional adjustments across a spectrum of sites and in a variety of images, from Barbara and Mother (2017) to Seagulls in Kitchen (2017) to Woman with Child (2017), or from Chief (2019) or Young Grandmother (2019) to her portrait of Rihanna wearing Dolce & Gabbana for Garage magazine.10 In her frames, orthogonal relationships between abutting walls warp seamlessly into sweeping diagonal lines; rigid rectilinear shapes become rhomboid, and at the center of these optical arrangements, in the crafted space of her portraits, Lawson figures a spectrum of black life in resplendent theatricality.

In Baby Sleep (2009), Daughter (2007), Nicole (2016), Greased Scalp (2008), and Sharon (2007), Lawson interweaves black feminine nudity, domesticity, maternity, and sexual play or bodily pleasure, so that the question of black femininity is bound up in sexuality, and in black women’s unstable purchase on the properties of normative gender.11 In these portraits, Lawson figures black feminine nudity in darkened black interiors opened up both by her camera’s lens, and by the mechanical ministrations of her camera’s flash. She constructs images that yield acts of revelation in which a certain violent intrusion is woven together with the studied and collaborative intimacy of the depicted scene. In these photographs, the explosive glare of the camera flash exaggerates tonal distinctions within a darkness that is, and crucially, always was prior to the camera’s programmatic intervention into the scene. This is to say that the black social/sexual practices intimated in Lawson’s artificially illuminated portraits preceded the intervention of the camera, and critically, were illegible to large-format film in the absence of artificial light: they quite literally could not otherwise be seen. What is “native” to the scenes at the moment prior to exposure is an opacity that resists differentiation: a blackness that miscegenates distinctions which white light explodes into clearly structured hierarchies. The sudden and sweeping luminance of the flash hyperbolizes the distance between black and white, revealed and obscured, known and irreversibly opaque. These aesthetic spectrums mold the differentiated figuration of black feminine sexuality, preserving in the images an opacity of black hair, black skin, of distant shadow that is keyed against the homogeneity and intrusiveness of the flash, which seeks to reveal everything everywhere at once in the intensity of photographic exposure.

The very speed of the camera flash obscures the forcefulness of its material intervention into the scene: the instantaneity of its artificial light, and of the exposure that that light facilitates, exclude the physical effects of the startling explosion of light on the bodies revealed. The embodied response to the presence of flash follows in the wake of the photographic frames that it illuminates. These flashes can, quite commonly, lead to a temporary but total blindness, to a thoroughgoing disorientation and discombobulation, and even to seizures. As Kate Flint has written, “Nothing startles and disrupts the gaze so much as a sudden flash of light,” in that it is “shocking, intrusive, and abrupt.”12 The flash has its roots in the chemical science of explosives. In social documentary traditions, it was deployed to forcefully illuminate abjection, such as in Jacob Riis’s photographic investigations of the living conditions of the urban poor, as well as in the (re)production of glamor in the picture press and through the dissemination of film stills.

Deana Lawson, Nicole, 2016. Copyright: Deana Lawson.

These alternating valences of veneration and subjection, of violent imposition and sociological concern, of militarized technology and liberal humanism are internal to the history of the materials and aesthetics of Lawson’s portraiture. The grammar of her photographs, in other words, is saturated by and acutely engaged with the forces of class distinction, racialization, and gendering. Her frames are shot through with the irregular oscillation of extremes that such processes produce in the simplest of interior acts. If this claim seems hyperbolic, we should recall the murders of black women like Breonna Taylor (March 13, 2020), Atatiana Jefferson (October 20, 2019), April Webster (December 16, 2018), and Geraldine Townsend (January 17, 2018) in their homes. We should remember Marissa Alexander’s near six-year incarceration for daring to fire a warning shot into the ceiling of her own home, to ward off a serial abuser of her person and menace to her life.

The parameters within which Lawson pictures such graceful exertions of black feminine sensuality are bordered by the logic and the reality of such acts. The textured intrusiveness of white light, the resistant opacity of black and brown flesh, the rote mechanical and scopic intervention of the camera’s lens—these interanimating aesthetic factors are laced with palpable resonances of complex historical forces, and uneven exercises of power. In the precincts of Lawson’s nude depictions of black femininity, it behooves us to recall that, as Daphne Brooks asserts,

black women’s bodies continue to bear the gross insult and burden of spectacular (representational) exploitation in transatlantic culture. Systemically overdetermined and mythically configured, the iconography of the black female body remains the central ur-text of alienation in transatlantic culture.13

Within and against such force, the assertions of black feminine sensual and sexual life figured in Lawson’s portraits can be understood as acts or practices of refusal—refusal of the strictures that seek to contain and order their bodies and their inner worlds. I cite such a term here in echo of Tina Campt’s theorization of black feminist futurity and Saidiya Hartman’s notion of redress.14 That is, I understand these imaged acts as part of a quotidian fabric of refusal of white supremacy’s refusal of black femininity, and as a reclamation of that which it would seek to deny. While such refusal is laced with confrontation, that confrontation need not be assumed spectacular or physical. Rather, in instances like those Lawson pictures, refusal figures as a contrapuntal evasion of the microphysics of white power—an assertion of an otherwise at the interstice, in the stolen moments shared within the penetrable interiors of black social life. These momentary regenerative practices of refusal make other worlds present, fleetingly, against the weight of the general tide, and rarely emerge in grand narratives of black resistance, despite their centrality to the lifeworlds that sustain black radicalism. As Hartman has argued:

Strategies of endurance and subsistence do not yield easily to the grand narrative of revolution, nor has a space been cleared for the sex worker, welfare mother, and domestic laborer in the annals of the black radical tradition. Perhaps understandable, even if unacceptable, when the costs of enduring are so great. Mere survival is an achievement in a context so brutal.15

Refusal, as I construe it in Lawson’s portraiture of black feminine nudity and sexuality, represents what Campt defines as “an extension of the range of creative responses black communities have marshaled in the face of racialized dispossession.”16 It is necessarily quotidian, and, because lived under conditions of white hegemony, necessarily fugitive. It closes off, even momentarily, the violence that assails black social life. Refusal, for Campt, consists of “practices honed in response to sustained, everyday encounters with exigency and duress that rupture a predictable trajectory of flight.”17 Refusal, in Lawson’s portraits of black feminine sexuality, registers an unapologetic indulgence in the primacy of flesh, touch, scent, beauty, companionship, the elasticity of embodiment, the graceful arrangements of domestic space, the immediate thrill of presence to oneself and others in a given social world.

Against the entrenched and continuous (mis)conception of black femininity as itself inherently excessive—that is, against the tactically brutal presumption that black femininity is possessed of and defined by “immoderate and overabundant sexuality, bestial appetites and capacities … and an untiring readiness … outstripped only by black females’ willingness”18—for Saidiya Hartman, “redress is a re-membering of the social body that occurs precisely in the recognition and articulation of devastation.”19 This is a practice that “takes the form of attending to the body as a site of pleasure, eros, and sociality and articulating its violated condition.”20 The pleasures unchained in the practice of redress attend to—and thus acknowledge, rather than disavow—“devastation” and the facts of a “violated condition.” For Hartman, redress “is an exercise of agency directed toward the release of the pained body … and the remembrance of breach … Redress is itself an articulation of loss and a longing for remedy and reparation.”21 Redress is a practice of care that knows and names the history of its need.

Deana Lawson, Eternity, 2017. Copyright: Deana Lawson.

In Lawson’s 2017 portrait Eternity, a statuesque and achingly beautiful young black woman stands off-center in a vibrant violet and purple room. To her left is a fabric-covered couch, its surfaces littered with colorful illustrated flowers budding against worn cream and faded cyan. A golden clock gleams above her, its base encircled by a looping thread of flowers that snake out to offer a branch for a rearing winged horse to perch upon. Subtle rhyming repetitions occur between the woman and the clock: the glimmering tassels of her dark navy underwear mimic the studded golden ornamentation of the clock face; the crook in her left arm mimics the crook in the forelock of the winged horse; the wavy grace of her black hair echoes both the horse’s mane and its tail, even as their faces take up comparably oblique relationships to the camera lens, and even as the circular form of the clock is perfectly echoed in the curvature of her near-naked behind.

The picture is a study of fullness and sparseness. Its nominal contents are minimal and neatly separated, yet its textured density, affectively and symbolically, is rich and complex. Eternity is everything, or rather always: it is the unbridled futurity of all photographic images within the confines of earthly life, and it is the spiritual dimension of the afterlife; it is an impossibly slow waiting for a new world to come, and the constant renewing vitality of the world that we unevenly share; eternity is the lot and gift of black women as “belly of the world.”22 If black feminine sexuality is inseparable from its historical violations, and in particular from its constant stigmatization as inherently excessive, Lawson figures its beauty here as given and withheld, as ineffable and mythic.23 Her portrait at once reveals and recesses its subject deep in its resonant folds, articulating in its compositional grammar a fundamental paradox in which beholding and holding black femininity figure at diametric extremes of care and subjugation. It is what Brooks has elsewhere termed a “discordant image of both circumscription and liberation,” or an image that mobilizes what Nicole Fleetwood dubs “the relations between aberrance and idealization.”24

I would argue that the fraught and electrifying oscillations in Lawson’s portraits (between agency and subjection, between protagonism and intrusion, between unveiling and receding) are not only consonant with Hartman’s theory of redress, but issue from the fact of redress’s profound imbrication in black women’s sustenance and survival of racialized embodiment. If, as Hartman writes, “it is impossible to separate the use of pleasure as a technique of discipline from pleasure as a figuration of social transformation,”25 then it is a measure of Lawson’s accomplishment that her portraits shuttle between poles of vulnerability and sublimity, between revelation and refusal, between spectacular scenes of sensuality and recondite practices of redress. In Lawson’s black interior, where we see these women, we hear Elizabeth Alexander’s incisive assertion that “the living room is a presentational space but at the same time, a private one.”26

3.

Racial and sexual fantasies are animating and integral features of Pfeiffer’s ongoing photographic series Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (2000–present). As physical prints, the images are imbued with a deep richness of color, and are given stentorian scale, measuring five feet in height or width. Pfeiffer frequently selects images for this series that define black athletes as protagonists whose bodies and gestures seem perfectly encased within the spectatorial armature of the stadium. In Four Horsemen #30, a player clad in a pristine white uniform floats above the wooden floor of the court, his rising figure perfectly centered within the frame, his right arm extended, slightly crooked, his left arm straightening in ascension toward the vaulted ceiling of the stadium. His toes are pointed toward the floor as his fingers reach for heaven in a resonant echo of Christ on the cross—the backward tilt of his head oscillating on a precipice between grace and agony. The scaling of the photographs—and by extension of the stadia—to the proportions of the player’s frames lends them outsize power as symbols of a form of virility whose history is grounded in threat, whether of white emasculation or of black sexual savagery.

That these proxies for Christ are black men surfaces, by allusion, the profoundly racialized whiteness at the center of Christian iconography. Where Christ is ethereal, they are thick and fleshly; where Christ is altruistic, they are mercenary. And yet vast swathes of people sit in rapt fascination around the wings of the court, their eyes pinned to the figures at the center of Pfeiffer’s frames, as the surface of their skin and of the courts beneath them shimmer under the spotlights. The deep absorption and delight of the audiences that surround these graceful performers recalls Cheng’s thinking about Shosho, whose dance onstage at the center of a nightclub in Piccadilly takes place at the base of a similarly vaulted space. Cheng writes that in that scene, light touches “not just Shosho but also the shimmering surfaces of the floor, walls, ceiling, and rapt faces all around, a net of light that literalizes the web of fascination. The light, acting as a dream and dreamer, unites the dancer and her spectators in a moment of visual and temporal trance.”27

In an essay on Pfeiffer’s series of prints, and his sculptural installations each titled Vitruvian Figure, the writer Nora Wendl observes that the “human body … is comfortably and historically the measure, module, and pattern for the body of architecture.”28 Pfeiffer’s Vitruvian Figure sculptures take two principal forms.29 The first form of Vitruvian Figure, produced in 2008 for the 16th Sydney Biennale, comprises an architectural model of an outdoor stadium in a massive architectural miniature—a vertically spiraling concentric array that comprises one million seats and that measures three meters wide at its narrowed base, and stands at eight meters tall and eight meters wide. The flared conical structure, modeled on the Stadium Australia, is a vast, hysterically centrifugal apparatus of compounding scopic weight that loops ever-upward in delirious verticality—the inner figuration of spiraling seats legible as a physical manifestation of the recursive structure of the loop that organizes so many of Pfeiffer’s video works.

Wendl recalls that, since as early as 900 BC, stadia “possessed mythical backgrounds and were understood, along with Greek shrines and temples, to re-establish connections with the divine,” thus traversing “a line between religious sanctimony and the destruction of life.”30 Stadia are infused, throughout their history, with the mutually constitutive forces of veneration and execration, of the ethereal and the visceral, the sacred and the profane. Wendl argues that “the modern stadium” functions in contemporary life as “a space of mass worship,”31 noting that in Renaissance cathedrals, the dome “stands metonymically for the whole building,” and “is where the unseen takes place: forces from above penetrate the church, and the dome is often resplendently arrayed to receive those.”32 In our moment, she writes,

the contemporary stadium is the one architectural typology that must allow, indeed encourage, the frenzy of its inhabitants to a point of discharge, while maintaining absolute control should that discharge spill over into riot … Speakers are located within the stands to amplify the crowd’s own sound to itself; cameras and LCD screens are installed to create images of the crowd, scaled up and made visible to itself. The stadium is now in every sense a mirror of the crowd, feeding back to itself, a closed and continuous loop without end.33

Wendl argues that “we can read Vitruvian Figure (2008) as the inversion of a dome … and see that the stadium is the ultimate centralized plan: completely circular, uninterrupted, infinite.”34 The centripetal form of the stadium materializes the serially extractive consumption of black athletic performance as something complexly bound up with polarities of veneration and execration. The Christ-like figures of floating black men that oscillate between grace and agony in Pfeiffer’s Four Horsemen images are resonantly situated at the center of the theater of American identity. Seen in this light, the Four Horsemen photographs can serve to heighten our sensitivity as viewers to the set of intense scopic and affective forces that transect the rippling bodies in their frames. As Pfeiffer has observed, in his engagement with footage of Muhammad Ali, gladiatorial contests of black athleticism reveal “a body attempting to operate in an intense perceptual condition … The pressure is intense. The boxer is there, practically naked, with everything written on his body, everything depending on his body.”35 The alternating airs of terror and the sublime that limn the figures in Pfeiffer’s images are, in this sense, an index of the cruel dichotomy that regulates the freedom that these black athletes enjoy. Pfeiffer’s works crystallize the reality that in the amplified sensory realms of sporting stadia, racial terror always marks the outer limits of transcendence in black performance.

However, in such spectacular images, the giant carapace of the sports stadium, as a massive figure in the municipal landscape, tends to vanish into the high drama staged within its confines. As we marvel or ponder at the sinewy force of the players, or at the resplendent shimmer that electrifies the inner surfaces of the arena, we should note how the stadium can fade into the luminescence of the spectacle. The edifice that houses these alternating currents of terror and transcendence is inseparable from entanglements of extraordinary athletic grace and irredeemable racial violence, and these elements melt together into spectacular opacity within the drama of the scene.

4.

Between 2000 and 2016, the US federal government funded stadium construction and renovation to the tune of $3.2 billion, added to which it offered windfall tax breaks to the holders of these bonds in the amount of $500 million, so that the total federal subsidy (separate from state funding) for franchise stadia amounted to $3.7 billion. The new Yankees stadium in the Bronx received $431 million of subsidy, added to which holders of the bonds issued by the federal government to pay for the construction received windfall tax breaks of $61 million. Residents of the Bronx received no such corresponding subsidy. Despite a total absence of statistical proof that stadium construction produces sustainable local economics gains, and despite the various ways in which it accelerates the violence of gentrification, such federal subsidy continues unabated.36 In this sixteen-year period, seven of the thirty teams in the National Basketball Association received comparable subsidies, twelve of the thirty Major League Baseball teams, and thirteen of the thirty-two teams in the National Football League. Such are the cruel facts of entanglement in the mass spectacle of American sport, and such are the “monstrous intimacies” in and through which black athletes perform grace in the bowels of racial capital.37 To quote Christina Sharpe: “the everyday violences that black(ened) bodies are made to bear are markers for an exorbitant freedom to be free of the marks of subjection in which are all forced to participate.”38

In the Four Horsemen images, Pfeiffer’s practice of erasure magnifies what remains. His aesthetic reduction of the visible produces an intense scopic weight, which centers on athletic black male figures who serve as incontrovertible proof of narratives of individual accomplishment, their ascension to hypervisibility from “troubled homes” suggesting a possibility that their very exceptional stature belies. Their very visibility as black men veils the violence that everywhere polices blackness. That veiling may be doubly cruel, to the extent that class privilege internal to blackness renders even more remote this elevated status. In the case of the NBA, as Nicole Fleetwood writes, “recent data indicate that most professional basketball players are from higher socioeconomic backgrounds and are raised in more affluent neighborhoods than their black male peers.”39

The post-produced solitude of these black figures thus takes on a double valence: it clears the visual field so that we might reckon with their individuated actions in a suspended moment freed from any plausibly instrumental usefulness: they are freed to float, to tense in exclamation, to linger without expectancy, but they are also bound to this expression of freedom as necessary substitutes for the ongoing lack of the same in the communities who hold them most dear. They are, to follow Sharpe, subject to the reality that their “desire to be free” requires that they “be witness to, participant in, and be silent about scenes of subjection that we rewrite as freedom.”40 To follow Fleetwood, their appearance must “substitute for the real experiences of black subjects.”41

Paul Pfeiffer, Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (07), 2002. 48 x 60 in, digital DuraFlex print. Copyright: Paul Pfeiffer. Courtesy the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

But a countervailing dynamic is at play in this series, and it emerges from the stilled interstice that the images’ careful abstraction generates. Every visible black male figure in Pfeiffer’s Four Horsemen series is rendered in an image that creates an interval outside of use. The gestures that they perform are use-less, as a consequence of their radical deracination from the flow of the games out of which they have emerged. In the absence of an identifiable end, their exertions, their voluble exaltation, their muscular expenditures of force, their prodigious proclamations of strength serve no ends beyond themselves. They are thus all excessive in nature, in that they exceed restraint, and are superfluous to productive work. David Marriott writes of blackness’ relationship to decadence:

Unless blackness is put to work as the figure of endless, unproductive labor, its “natural” course will assert itself as an exaggeratedly inflated figure of inflation; or, rather, the way that blackness puffs itself up when possessed of capital is actually a sign of decadent inutility, as in the case of an excess noteworthy for its unproductive labor: bling bling.42

Lawson’s nocturnal portrait Signs (2016) figures such “decadent inutility,” in which five shirtless young black men stand together in enactment of a semaphore of hand signs, their muscular and tattooed torsos glimmering in chocolate and caramel hues against the dark.43 Two men cast thumbs down at the camera lens, while another throws up a W and a middle finger. Their signaling is seemingly prompted by the theatrical intrusion of the camera flash; their lithe, celebratory refusals of the lens, their illegible codes of symbolic discourse, preserve an opacity that the camera cannot break down. They “do” their bodies in registers of action that conform to no organizing logic of sense or reason, making a scene in which they figuratively and gesturally refuse to be seen. In this refusal, their performance asserts what Stefano Harney and Fred Moten have also recently declared: “Blackness is unwatchable because there’s no way to watch it that ain’t in it, no way to watch it from the outside, which is to say from its anti-black and worldly effects: politics, policy, legality.”44

Read against the grain of antiblackness, Pfeiffer’s erasures in Four Horsemen militate against abjection, and can be read as insurrectionary threat to racial capital. If these athletes, like Lawson’s gilded black men, are now willfully off-script, out of order, on the fly, in the break, they figure not merely a uselessness in relation to productive activity, but an ever-proliferating and degenerating cessation of labor, and a joy in the very fact of their black embodiment. With each new image in Pfeiffer’s series, their number grows, in echo of the symbolism of contagion that has always figured black gathering as internecine threat to white supremacy. With every new image in the series, their general strike against conscription into productive labor acquires richer, more expansive resonance. As Marriott goes on to write, “Blackness is seen as both exorbitant and impoverished, both decadent and deliriously perverse.” For Marriott, blackness represents “an entity driven to negate the very idea of accumulation.”45 We might then consider that the emphatic uselessness of the actions Pfeiffer images in Four Horsemen is consonant with the apocalyptic tenor of the work’s title: that such a general strike against use, and thus value, occasions the end of the world.

In the summer of 2020, an actual player’s strike spread across the NBA, led by black players in vehement opposition to antiblack violence. Their mobilization yielded a league-wide commitment to open up their stadia as voting booths during a presidential election in which access to the polls was violently policed to restrict black and brown votes.46 So, a part of what is at stake in the stoppage of Pfeiffer’s frames, or in the recalcitrance of Lawson’s Signs, is the degenerating power of willful and unincorporated black performance outside the registers of common sense. The negation of use that grounds the performances in their images unearths a deeper white anxiety at blackness’ lack of restraint, and its intemperate hostility to discipline. Lawson’s and Pfeiffer’s images depict their subjects enjoying what Daphne Brooks describes as “ways of ‘doing’ their bodies differently in public spaces.”47 This may seem a minor point, but the unceasing stream of instances of unarmed black death at the hands of officers of the state evidences the paucity of safe spaces in American life for the combustible expression of black male athleticism in all its muscular and hyperanimated forms.

Both Lawson and Pfeiffer return to these actions an independence that exists only within the precincts of the image. Their aesthetic strategies preserve a stage on which to momentarily elude the constraints that dictate the value of these massively surveilled and deeply commoditized black bodies. While that stage may only be rhetorical, the space itself purely symbolic, the generative force of their images lies in the persuasive depth of the suspended animation that they create—in their uncanny interventions against the general flow of common sense.

Cheng argues that in Piccadilly, “Wong negotiates crushing corporeal objecthood by assuming a kind of resistant objectness.”48 I would argue that Lawson’s Signs and Pfeiffer’s Four Horsemen afford the same “resistant objectness” to the black men whose tensed and undulating figures float in the voided space of these images. In the Four Horsemen, the ecstatic stillness of the frames, the petrified gestures in each act, the deep disjuncture produced by the deracination of means from ends leave the players in a sort of citational intermission—literally in parenthesis—as something digressive, something set aside and contained. The works proffer objectness as a form of reprieve, reminding us, as Fred Moten does, that the “history of blackness is testament to the fact that objects can and do resist.”49

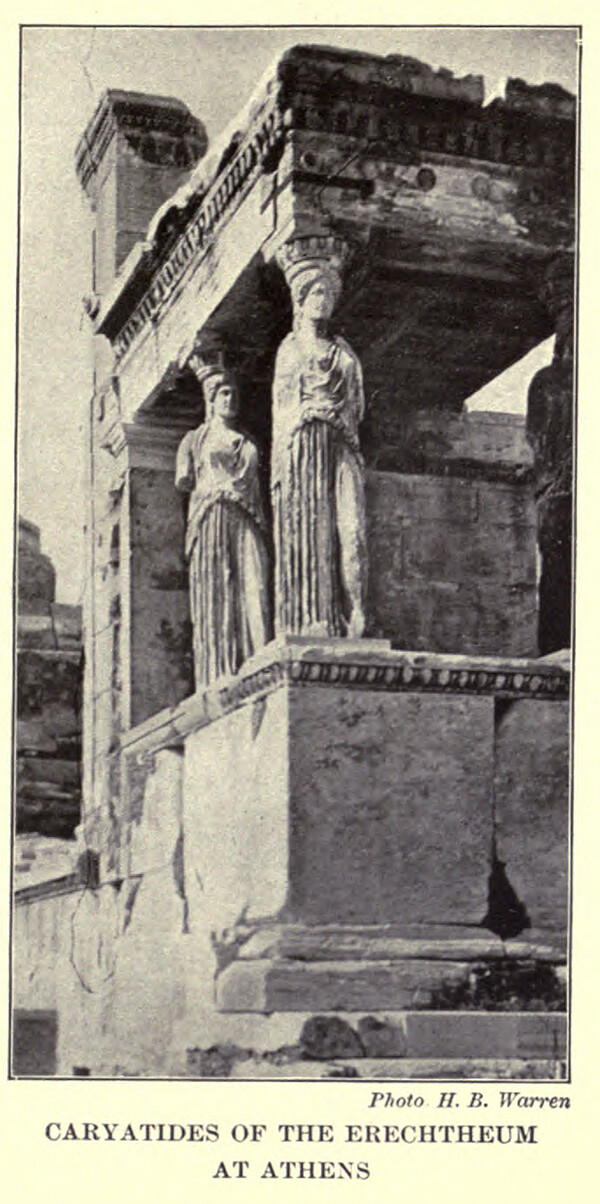

Caryatids of the Erectheum (Erechtheion) in Athens. Illustration from the translation of Vitruvius’s The Ten Books on Architecture by Morris Hickey Morgan with illustrations prepared under the direction of Herbert Langford Warren. Photograph by H. B. Warren, brother of Herbert.

5.

The provisional and contingent assertion of black humanity is dependent upon the spectacle of its constant (re)performance. The resonances of that cruel, brutalizing fact move through Lawson’s and Pfeiffer’s explorations of spectacular visuality. In particular, Lawson’s portraits demonstrate how it is that blackness, black embodiment, black interior social life in all its resplendence and irreducible differentiation, in its volubility and stoic refusal, in its performative grace and artful abstention, cannot be both accurately and simply described. This intractable fact constitutes something of a problematic antagonism within normative artistic and scholarly appreciations of black social and familial portraiture, for whom affinities “against innocence,” to borrow from Jackie Wang—attachments to deviant embodiment and intemperate performance—trouble the viewer’s desired enjoyment of figurations of black civility and dignity, which tend to ratify the white liberal project.50

In 2015, Lawson travelled to Gemena, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and produced an extraordinary nude double portrait entitled The Garden, in which a couple sits in wild grass and towering weeds at the edge of a wood in an unmarked field. In it, a black woman’s shoulder-length wavy black hair is unbundled and let loose in echo of the wild weeds around her, as a gracefully muscled man seated alongside her extends his left hand to cup or cover her swollen belly. Lawson has pictured pregnancy in Gemena before, in an interior portrait entitled Mama Goma (2014) in which the distended belly of a young, pregnant black woman protrudes neatly through a circle cut into her shimmering peacock-blue dress. In the former portrait, the couple’s gazes miss each other as consternation ripples the silvered brow of the pregnant woman. In the latter image, the woman’s hands are upturned in a figuration of receptivity and dutiful observance, even as her wary eyes gaze levelly at the camera lens with guarded circumspection.

I cannot but see these two images in dialogue: the earlier picture’s circular (surgical?) excision is answered, obliquely, by the sheltering hand in the latter portrait.51 The violated status of black maternity, and thus the ungendering of black femininity, sit at the center of both images as immanent threat and historical ground. The patterning of gestures surrounding black maternity in both portraits figures supplication, removal, veneration, invasion, and patriarchal protection as a set of forces that swirl—indeterminately but potently—around the black womb.

African women’s open vulnerability to death from pregnancy is unutterably extreme.52 For every hundred thousand births in Europe, ten mothers will die from pregnancy; in North America, eighteen mothers will die; in Sub-Saharan Africa, 542 mothers will perish.53 The odds of an adult woman in Europe dying from pregnancy are one in 6,500; in North America they are one in 3,100, and in Sub-Saharan Africa they are one in thirty-seven.54 In a moderated echo of the same lethal extremity, black babies born in the United States are more than twice as likely to die as white babies—“a racial disparity that is actually wider than in 1850, 15 years before the end of slavery, when most black women were considered chattel.” Black women are “three to four times as likely to die from pregnancy-related causes as their white counterparts.”55 This is to say that the term “life” is profoundly attenuated in its applicability to blackness, and that such extremity is the ubiquitous surround of the familial regeneration depicted in portraits like these.

Myth and mastery play into the vibrant complexities of the Gemena portraits. The Garden becomes an Edenic setting for the originary birth of human life, the portrait’s biblical title echoing the historical itinerary of human evolution and siting Africa, and thus blackness, at the root of the species. Mama Goma is rendered as a dubious and reluctant icon, her pale-blue figure glistening in stark contrast to the dour palette that surrounds her, the decorative textures of her clothing reflected in the faux flowers sitting atop the armrest of a sofa at her left-hand side. Lawson’s story of origins, in other words, her fable of fecundity and its embeddedness in black femininity, is laced with ambivalence, artifice, circumspection, and disconnection, even as both images ripple with sensuous beauty and tender grace. Life-giving, as burden and as gift, is rendered in profound complexity—in scenes that insist on the central role of black sexual reproduction in the history of the world.

Lawson’s exploration of black maternity—a role that she both lives and depicts—insists through scale and resplendence on a reversal of black maternity’s programmatic occlusion from the history of our present. Since blackness continues to be predictive of disproportionate death and suffering, and since that loss and suffering falls disproportionately on the shoulders of black women, the question of sustaining black life is necessarily historical and political, and Lawson’s portraits of black women—pregnant, nude, or otherwise—locate black feminine labor at the heart of black social life. They do so without recourse to trite simplicity or crass honorific “dignification,” insisting always on the reality of complexity, on the fact of ambivalence, and on the importance of sensitivity for the tensed extremes within which black life unfolds.

Photographs like Flex (2010) and White Spider (2019) demonstrate Lawson’s indifference to a politics of civility or uplift, as she pictures black women reveling in the athletic exertion of their corporeity and refusing the identificatory drive of the camera. Both images depict black women stood with their backs to the camera, bent double at the waist to thrust their rears frontally at the lens. In the former, a dancer clad in ripped jean shorts and thigh-high black boots with high heels torques her body through an improbable contortion, so that her torso is folded backward through her knees and up toward her hips, as she gazes up at her own behind from behind it. In the latter, a woman’s triangular spreadeagle turns her small, distant peaking head into an echo of infant birth. The foreshortening perspective of the lens conflates rear and head into flattened proximity, so that her face sprouts in stunted suddenness from the far end of her inverted figure, which gleefully moons the camera.

Both women are imaged in the praxis of what Nicole Fleetwood calls “excess flesh,” a mode of visuality in which black performance makes visible the gendered and racialized constraints against which it strives, and according to which it is valorized. Fleetwood defines excess flesh as “a performative that doubles visibility,” a practice through which we are able “to see the codes of visuality operating on the (hyper)visible body that is its object.”56 For Fleetwood, excess flesh is “an enactment” that “can be productive in conceiving of an identificatory possibility for black female subjects,” and while it is “not necessarily a liberatory enactment,” it “can work productively to trouble the field of vision.”57

I am reminded of such black feminine exertions and exultations, by what it is that they bare and bear, in the etymological resonances of the term “caryatid,” which names Pfeiffer’s ongoing series of video works. Derived from Greek, it names the architectural element of a sculpted female figure that serves as columnar support for an entablature that rests atop her head. The figure is famously named in Vitruvius’s first-century BC text De Architectura as a metonym for the women of Caryae, who were enslaved and “doomed to hard labor because the town sided with the Persians in 480 BC during their second invasion of Greece.”58

Pfeiffer’s appropriation of the term re-genders the black and brown men who writhe and stumble under the punitive force of the invisible blows that bounce them around the boxing ring in the Caryatid series. Naming them as such fixes them in the position of expressly feminine support for an architecture to which their bodies are powerfully subjected, and which they must at once uphold. In architecture, male-gendered columnar supports are called “atlases,” so the substitution of terms and the symbolic transposition of gender roles seems intentional. It figures anti-imperial feminine resistance to power right alongside the foundational force of feminine subjection.

This doubling of force, this braiding of subjection with service, so powerfully marks the historical formation of black femininity as to problematize the racialization of gender at play in the Caryatids. Is it possible to construe the male receipt of unmarked blows in these videos as analogue to the sufferance imposed upon racialized women? Is the thrill of pugilistic violence meted out between male-gendered black and brown bodies analogous to feminized labor? Is it possible to view the spectacle of these men’s subjection to ceaseless attack as expressive of the history of race’s multiple differentiating distortions of gender?

The name Caryatid also recalls to me the absence of women as organizing figures in Pfeiffer’s elaboration of the intersections between race, nation, gender, and spectacle running through his work on sports. The faint echo of the women of Caryae points up the differentiated balance of forces at play in the perceptual and (bio)political conditions in which Serena Williams, Simone Biles, Caster Semenya, or Naomi Osaka conduct black performance within comparably spectacular athletic scenes. The “perceptual conditions,” the circumstances in which “everything depends upon their bodies,” vary profoundly as gender distorts and refigures notions of agency, and thus the politics of subjection operative at every instant of their entanglement in spectacular visibility.

6.

But what if we took a different turn? In returning to Caryatid (Broner), what if we were to say that the blankness of the unseen force that assaults the boxer is internal to blackness? What if we were to suggest that the scene is not one of racial antagonism, but a struggle over the politics, the virtues, and forms of black legibility? Rather than envisioning a monolithic black/white antagonism, might the work stage a conflict not merely between presence and absence, but also between reform and radicalization, reparation and abolition, property and errantry, Reconstruction and the end of the world? What if the obliterating force of the invisible opponent seeks instead to erase Broner from the visible field, which is to say: What if what appears as conflict is in fact an exercise of care, an effort at recuperating and enfolding black flesh back within the thinned envelope of camouflaged skin? As philosopher Denise Ferreira da Silva wrote in that same summer of the NBA players’ strike:

Any imaging of otherwise in this world requires contending with the scene, the scene of violence, and with that which captures the when, how and where a black person was killed by a police officer. The creative work … must face squarely the ethical-political challenge of working with the visual nowadays, which is to find the balance between visibility and obscurity.59

While appearance constitutes a fraught invitation for racialized minorities who typically attain visibility only in exception, the grammars of both Pfeiffer’s and Lawson’s work reflect a shift of “attention away from the visibility of race to its visuality,”60 to borrow from Cheng, and point toward resistant strategies that complicate the recuperation of dissident performances within violent regimes of racial difference. As Hartman reminds us, and as I would argue both artists’ work shows, “strategies of domination don’t exhaust all possibilities of intervention, resistance, or transformation.”61 It behooves us to attend to “the myriad and infinitesimal ways in which agency is exercised” under conditions of white supremacy—to attend to refusal, fugitivity, opacity and redress.62 Following Daphne Brooks, it behooves us to attend to “the counter-normative tactics used by the marginalized to turn … horrific historical memory … not only into a kind of ‘second sight,’ as DuBois would have termed it, but also into a critical form of dissonantly enlightened performance.”63

For Shosho, in Piccadilly, “resistant objectness” constitutes an act of fugitivity—a mode of escape into illegible and inaccessible interiority. Part of what is arguably at play in her acts of “surrogacy,” as Cheng dubs them, part of what is at stake in her derangement of norms of gendered and racialized availability, is the creation of an opaque space into which one might recede, not merely squarely within the field of the visible, but at its overdetermined spectacular peak.64 In Cheng’s analysis of Shosho, she argues that it is at the site of celebrity’s intersection with glamour and spectacle that one can think together “the intimacy, rather than opposition, between agency and objectification, personality and impersonality.”65 Where we may have traditionally thought objectification an unmitigated ill effect of racism, Cheng argues that it can constitute constrained but effective agency.

It is crucial that we reckon with the particular nuances of “spectacular opacity” in this context.66 Brooks’s phrase elucidates the difference between visibility and visuality—between phenomenon and practice. It designates practices that elude the violent imposition of raced and gendered difference through tactical engagements with spectacular scenes. Spectacular opacity is essential to those inhabiting bodies marked as the special sites of “sights.”

Opacity here does not mean absence in relation to some simple act of erasure. Rather, following Brooks, opacity offers us a “trope of darkness” which “paradoxically allows for corporeal unveiling to yoke with the (re)covering and re-historicizing of the flesh” in performances that “contest the ‘dominative imposition of transparency’ systemically willed on to black figures.”67 Spectacular opacity is generated in performances that preserve a resistance to interpretation and illumination on the part of racialized bodies while they simultaneously participate in a bodily unveiling within the scene. As Brooks continues, “‘opacity’ in this context characterizes a kind of performance rooted in a layering and creating a palimpsest of meanings and representations … ‘Opacity’ is never an absence but is always a present reminder of … the complex body in performance.”68 Spectacular opacity is the product of a capacity to enter into the visible in an exclusionary inclusion, in a mode that masks a voided space in the resplendent surfacedness of a wholly ethereal presence.

7.

I am staring at a glimmering image in the dark of my apartment. I’ve dimmed all the lights, it’s nighttime, my glass desk is faintly illuminated by the papery blue glare of the laptop monitor, and its sharp reflection enables me to read my prose unfold in stuttering sentences that move left to right both above the glass surface and below it. I watch thirty seconds of Pfeiffer’s Live Evil (Seoul) (2015–18). In it, the gold-suited figure of Michael Jackson seems to shuffle his own body like an interlacing deck of cards, dicing his arms and shoulders like wafers slipping into the thinned space between silver coating and glass inside the tightly compacted layers of a mirror. His body seems somehow to be comprised of nothing but mirrors.

As he weaves and stutters with machinic grace, his arms move through impossibly replicating duplicated gestures, alternately collapsing through his body and multiplying outside of it. This sense of perpetual mirrored motion is emphasized by the palindromic structure of the work’s title: Live Evil. In it, the gap between the title’s two principal terms is occupied by a double-sided mirror, suggesting that a concentric and cyclical structure bonds the outer edge of each term to its other in serial re-reflection. In the work, through the iterative repetition of mirrored displacement and serial reflection, Jackson becomes Shiva Nataraja, the Hindu symbol for the god Shiva imaged in three roles simultaneously: as creator, preserver, and destroyer—the embodiment of life’s cyclical rhythms. Shiva is known as the “trembling snake,”69 and in Pfeiffer’s work, Jackson becomes an ouroboros of infinite repetitions: at once subsiding into shade and shimmering into electric light, extending and collapsing, advancing and retreating, serially splicing itself into ever more dichotomous reflections.

The symbolic and haptic intensities and ritual observances of religious practice intersect, in the grammar of the work, with secular mass-cultural practices of idolatry, and these forces are tightly bound up with race. The black bodies of iconic figures like Larry Johnson, Patrick Ewing, Kevin Garnett, and Michael Jackson are transected by intense aesthetic forces and symbolic investments in Pfeiffer’s works, but they are also liberated—strangely and ephemerally—from servicing the instrumental ends for which they have been granted exceptional status.

In Lawson’s portraiture, the acute difficulty and the irreducible risks of appearance for black bodies—the fraught interanimation of visibility with availability—is mitigated by her doubled deployment of a threshold that intervenes between the perceiving eye and the depicted body. I say doubled, since Lawson’s proscenium works to both theatrically reveal and materially recess black bodies deep within her frames. It animates and stages a performance while distancing its subject, and deferring the appetitive consummation of the desires that her images engender. This is a spectacular opacity that recedes into view.

Pfeiffer’s work unveils the deeply racialized and commoditized politics of visibility to which iconic black bodies are subject, calling into question the virtue and value of black visibility under white supremacy. Neither artist cultivates an aesthetic that uncomplicatedly affirms the dictum that representation constitutes power and preserves agency for the structurally subordinated. Rather, their aesthetics interrogate the normative value of visibility and proffer a politics of visuality in which blackness at once appears and retreats. In their work, raced subjects cultivate a visuality of fugitive evasion, or, to borrow from Cheng, they manifest “a disappearance into appearance.”70 Such fugitive practices are essential to the survival of racialized subjects, in that their “methods … transform the notion of ontological dislocation into resistant performance.”71 Their works not only reckon with the violent dispossessive incorporation of racial difference within the field of the visible, they suggest that the very violence of objectification might offer a critical, restorative form of reprieve, since, as Cheng writes, “it is the overcorporealized body that may find the most freedom in fantasies of corporeal dematerialization.”72

Up on the stage, in the dark of my apartment, Jackson performs a complete collapse in the solidity of a division between interior and exterior. He pirouettes through a mirrored vortex of reflections and refractions of movement that interpenetrate what I strain to define as a threshold between inside and outside. Both sides are continually sublated into one another, and with them the distinction between subject and object, as he elopes in a fugitive evasion from fixity that passes not into obscurity or shadow, but that condenses into extraordinary, luminescent hypervisibility. On my screen, here in the dark, Jackson fades into a brightness that shimmers and is utterly opaque; he fades off into a kind of radiant kaleidoscopic series of endless divisions and repetitions, and the absence of any meaningful distinction between inner and outer leaves only the residue of action, of a movement that cannot be held. Without a resistant, thickened, dimensional solidity, without what we can fix as “body,” nothing is retained. In Live Evil, Jackson gives us blackness as envelope without interior, blackness as “nonperformative presence,” refraction without matter, blackness as a condensation of shadow into pure light.

The phrase and analytic “spectacular opacity”—from which the title of this essay is derived—was developed by Daphne Brooks in Bodies in Dissent: Spectacular Performances of Race and Freedom, 1850–1910 (Duke University Press, 2006), 8.

Nicole Fleetwood, Troubling Vision: Performance, Visuality and Blackness (University of Chicago Press, 2011), 6.

Fred Moten, “Some Propositions on Blackness, Phenomenology, and (Non)Performance,” in Points of Convergence: Alternative Views on Performance, ed. by Marta Dziewańska and André Lepecki (Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, 2017), 102.

Anne Anlin Cheng, “Her Own Skin,” in Second Skin: Josephine Baker and the Modern Surface (Oxford University Press, 2011), 6.

Sable Elyse Smith, “FEAR TOUCH POLICE,” The Swiss Institute, October 27, 2020–January 14, 2022 →.

Anne Anlin Cheng, “Passing, Natural Selection, and Love’s Failure: Ethics of Survival from Chang-Rae Lee to Jacques Lacan,” American Literary History 17, no. 3 (Autumn 2005): 555.

Cheng, “Passing,” 555.

Cheng, “Passing,” 555.

Cheng, “Passing,” 558.

Cheng, “Shine: On Race, Glamour, and the Modern,” PMLA 126, no. 4 (2011): 1027.

See →.

“What place does the enslaved female occupy within the admittedly circumscribed scope of black existence or slave personhood? As a consequence of this disavowal of offense, is her scope of existence even more restricted? Does she exist exclusively as property? Is she insensate? What are the repercussions of this construction of person for the meaning of ‘woman’? … The law’s selective recognition of slave personhood … failed to acknowledge the matter of sexual violation, specifically rape, and thereby defined the identity of the slave female by the negation of sentience, an invulnerability to sexual violation, and the negligibility of her injuries … What is at stake here is not maintaining gender as an identitarian category but rather examining gender formation in relation to property relations, the sexual economy of slavery, and the calculation of injury.” Saidiya Harman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (Oxford University Press, 1997), 97.

Kate Flint, “Prologue,” Flash! Photography, Writing, and Surprising Illumination (Oxford University Press, 2018), 1.

Daphne Brooks, Bodies in Dissent: Spectacular Performances of Race and Freedom, 1850–1910 (Duke University Press, 2006), 7.

Campt defines black feminist futurity as “a tense of anteriority, a tense relationship to an idea of possibility that is neither innocent nor naive … The grammar of black feminist futurity … moves beyond a simple definition of the future tense as what will be in the future … It strives for the tense of possibility that grammarians refer to as the future real conditional or that which will have had to happen. The grammar of black feminist futurity is a performance of a future that hasn’t yet happened but must … It is the power to imagine beyond current fact and to envision that which is not, but must be. It’s a politics of pre-figuration that involves living the future now.” Tina Campt, Listening to Images (Duke University Press, 2017), 17.

Saidiya Hartman, “The Belly of the World: A Note on Black Women’s Labors,” Souls 18, no. 1 (January–March 2016): 171.

Campt, Listening to Images, 10.

Campt, Listening to Images, 10.

Harman, Scenes of Subjection, 86.

Harman, Scenes of Subjection, 76.

Harman, Scenes of Subjection, 77.

Harman, Scenes of Subjection, 77.

Hartman, “Belly of the World.” As Hartman incisively observes: “It has proven difficult, if not impossible, to assimilate black women’s domestic labors and reproductive capacities within narratives of the black worker, slave rebellion, maroonage, or black radicalism, even as this labor was critical to the creation of value, the realization of profit and the accumulation of capital. It has been no less complicated to imagine the future produced by such labors as anything other than monstrous” 167.

In a sense, Lawson’s photographs of nude black women raise and engage questions formulated by Nicole R. Fleetwood: “Can hypervisibility be a performative strategy that points to the problem of the black female body in the visual field? Can visuality be deployed to redress the excessive black female body?” Troubling Vision, 110.

Brooks, Bodies in Dissent, 77. Fleetwood, Troubling Vision, 117.

Hartman, Scenes of Subjection, 78.

Elizabeth Alexander, The Black Interior (Greywolf Press, 2004), 9.

Cheng, “Shine,” 1026.

Nora Wendl, “Vitruvian Figure(s),” in Contemporary Art About Architecture: A Strange Utility, ed. Isabele Loring Wallace and Nora Wendl (Ashgate, 2013), 254.

The second, Vitruvian Figure (2009), is a large-scale sculpture that stands at approximately two-and-a-half meters tall, six meters wide, and five meters long, and comprises a massive architectural miniature design of a curved wooden seating array, which is cut like a section from an outdoor sports stadium in the concentric form of the Roman Colosseum. The cut section is typically encased by a stainless-steel and two-way-mirrored glass wall in an L shape that encases the cropped section of concentric stadium seating on both its long edges, so that from the exterior of the sculpture the wooden seating is clearly visible. As one turns a corner to stand inside the crook of the L-shaped glass-and-steel wall, the mirrored surface of the wall reflects this one section in each direction, turning the triangular fragment into a circular whole in the polished surface of the glass.

Nora Wendl, “Body Building: Paul Pfeiffer’s Vitruvian Figures” (lecture, 99th Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture (ACSA) Annual Meeting, Where Do You Stand, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, March 3–6, 2011). Published in conference proceedings, 521–26 →.

Wendl, “Vitruvian Figure(s),” 255.

Wendl, “Vitruvian Figure(s),” 260.

Wendl, “Vitruvian Figure(s),” 263.

Wendl, “Vitruvian Figure(s),” 264.

Paul Pfeiffer, interview by Jennifer Gonzalez, BOMB, no. 83, April 1, 2003 →.

“There is little evidence that stadiums provide even local economic benefits. Decades of academic studies consistently find no discernible positive relationship between sports facilities and local economic development, income growth, or job creation. And local benefits aside, there is clearly no economic justification for federal subsidies for sports stadiums.” Alexander K. Gold, Austin J. Drucker, and Ted Gayer, “Why the Federal Government Should Stop Spending Billions on Private Sports Stadiums,” Brookings Institute, September 8, 2016 →.

I borrow the phrase “monstrous intimacies” from Christina Sharpe, Monstrous Intimacies: Making Post-Slavery Subjects (Duke University Press, 2010).

Sharpe, Monstrous Intimacies, 4.

Nicole Fleetwood, On Racial Icons: Blackness and the Public Imagination (Rutgers University Press, 2015), 91.

Sharpe, Monstrous Intimacies, 23.

Fleetwood, Troubling Vision, 13.

David Marriott, “On Decadence: Bling Bling,” e-flux journal, no. 79 (February 2017) →.

See: →.

Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, All Incomplete (Minor Compositions, 2021), 53.

Marriott, “On Decadence.”

Samantha Rafelson, “NBA Agrees To Use Arenas As Polling Places In Deal To Resume Playoffs,” NPR, August 28, 2020 →. After Jacob Blake was shot seven times in the back in front of his infant sons on August 23, 2020, the Milwaukee Bucks led a proliferating series of walkouts during the NBA playoffs that led to the threat of a general strike. Part of the settlement achieved with the players involved NBA franchises opening up their stadia as sites in which to cast votes in the presidential election that fall. While the electoral implications of the player’s protests were no doubt consequential to the outcome of the election, three days before the NBA announced the league’s expansion of access to the democractic franchise, white seventeen-year-old Kyle Rittenhouse travelled from Illinois to Wisconsin, armed with an AR-15 rifle, and deputised himself in armed “defense” of the police. In a confrontation with peaceful protesters, he shot dead two unarmed people and injured a third. Always, black political agency within the confines of white institutions exacerbates the painful distinction between reform and abolition.

Brooks, Bodies in Dissent, 8.

Cheng, “Shine,” 1030.

Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 1.

Jackie Wang, “Against Innocence: Race, Gender, and the Politics of Safety,” LIES Journal, vol. 1 (2012) →.

In Lawson’s debut monograph, Mama Goma is the third image in the sequence of the book, and The Garden is the book’s final image. The first image of the book’s sequence (Baby Sleep, 2009) also figures black maternity through a portrait of a nude black woman, situating black femininity, maternity, and sexuality as the central seam of the book as a whole. See Deana Lawson, Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph (Aperture Foundation, 2018).

Maternal death is defined as “the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management but not from unintentional or incidental causes.” World Health Organization, Trends in Maternal Mortality 2000–2017: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and United Nations Population Division, September 19, 2019, 7 →.

World Health Organization, Trends in Maternal Mortality 2000–2017.

These ratios are defined as “lifetime risk of maternal death.” See Trends in Maternal Mortality 2000–2017, 35.

Linda Villarosa, “Why America’s Black Mothers and Babies Are in a Life-or-Death Crisis,” New York Times Magazine, April 11, 2018 →.

Fleetwood, Troubling Vision, 112 (emphasis in original).

Fleetwood, “Excess Flesh,” 122, 112, 113.

“Caryatid,” Encyclopedia Britannica →.

Denise Ferreira da Silva, “Thoughts of Liberation,” Canadian Art, June 17, 2020 →.

Anne Anlin Cheng, “Do You See It? Well, It Doesn’t See You!” interview by Tom Holert, in “Supercommunity,” special issue, e-flux journal, no. 65 (2015) →.

Hartman, Scenes of Subjection, 56.

Hartman, Scenes of Subjection, 56.

Brooks, Bodies in Dissent, 5.

Cheng, “Shine,” 1030.

Cheng, “Shine,” 1023.

Brooks, Bodies in Dissent, 8.

Brooks, Bodies in Dissent, 80.

Brooks, Bodies in Dissent, 8n13.

“Nataraja,” Encyclopedia Britannica →.

Cheng, “Shine,” 1038 (emphasis mine).

Brooks, Bodies in Dissent, 3.

Cheng, “Shine,” 1032.

Category

This essay is adapted from an earlier version published in Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, Dark Mirrors (MACK, 2021), 213–40.

With thanks to Kaye, Ariel, Emma, Leslie, Allie, and to Kevin for the huge video assist.