This essay is the first of “After Okwui Enwezor,” an e-flux journal series that reflects on the resounding presence of the late writer, curator, and theoretician Okwui Enwezor (1963–2019). Along with a focus on his many innovative concepts like the “postcolonial constellation,” the series presents a wide evaluation of Enwezor’s curatorial and theoretical practice following other similar initiatives, such as the special issue on Enwezor by the journal he founded, Nka Journal of Contemporary African Art. Moving beyond tributes and biography, this series will cover topics such as the relevance of Enwezor’s approach to politics, the limits of the exhibition as a form for critique, his conception of modernity and writing on the contemporary, his nomadic epistemology, accounts of his biennials in Seville, Paris, and Venice as institutional critique, and the specific contribution of non-Western artists in the art world.

—Serubiri Moses, Contributing Editor

***

The great literary work … would thus be one that would deconstruct, then reconstruct these clichés.

—Maryse Condé

1.

There are gaps in our understanding of African art and its exhibitions, particularly exhibitions that lie beneath the radar of “must see” shows in New York by well-known curators and artists. It’s hard to remember just how many such shows there have been—that is, once we have ticked off the big names. This realization came to me after the revered critic Holland Cotter said in a 2021 presentation that, since Okwui Enwezor passed away in 2019, there had been few or no exhibitions of African art to speak of.1 Cotter’s presentation was a lecture on his professional journey as a writer, from his childhood in Boston to his tenure at the New York Times. Cotter acknowledged the influence of both Asian and African art on his sensibility as a critic, and his understanding of the world at large. Yet during the Q and A, he made a largely unsubstantiated claim about the lack of African art exhibitions. I am interested in returning to this claim not to admonish a beloved critic, but rather to take stock of what it means to arrive at such a conclusion. I’ll do so through a postmortem review of Enwezor’s curatorial career, as well as a survey of African art exhibitions in New York from 2004 to date.

Enwezor, who was born in Calabar, Nigeria in 1963, arrived in the United States in the early 1980s to study political science at a New Jersey college. He went on to write poetry before founding the contemporary African art journal Nka in 1995. His first curated museum exhibition was at an art center in New Jersey, but he became known in the art world first through Nka, and then the exhibition “In/Sight: African Photographers 1940 to Present” at the Guggenheim in 1996. He was the first Black or African guest-curator to organize an exhibition at the museum since its founding in 1939. The second would arrive more than fifteen years later.2 In response to Cotter’s statement, I have produced a list of thirty exhibitions of African art that have taken place in New York City from 2004 to 2024, according to criteria I’ll discuss below.3 In addition to many solo and group shows, these include three of Enwezor’s exhibitions—his magisterial surveys of African and contemporary photography at the ICP museum. What does Cotter’s overlooking of these exhibitions mean in relation to the field of art? What does this oversight show about the gaps that exist in the art-historical understanding of what has happened in this field since 2004? New York City is regarded as the center of the art world, and this article considers the city and its context, because the specificity of New York City matters when thinking about any evaluation of art and its distribution, including African art. I also focus on New York City as the primary locus of Enwezor’s operations for most of his career (his other main locus was Germany).

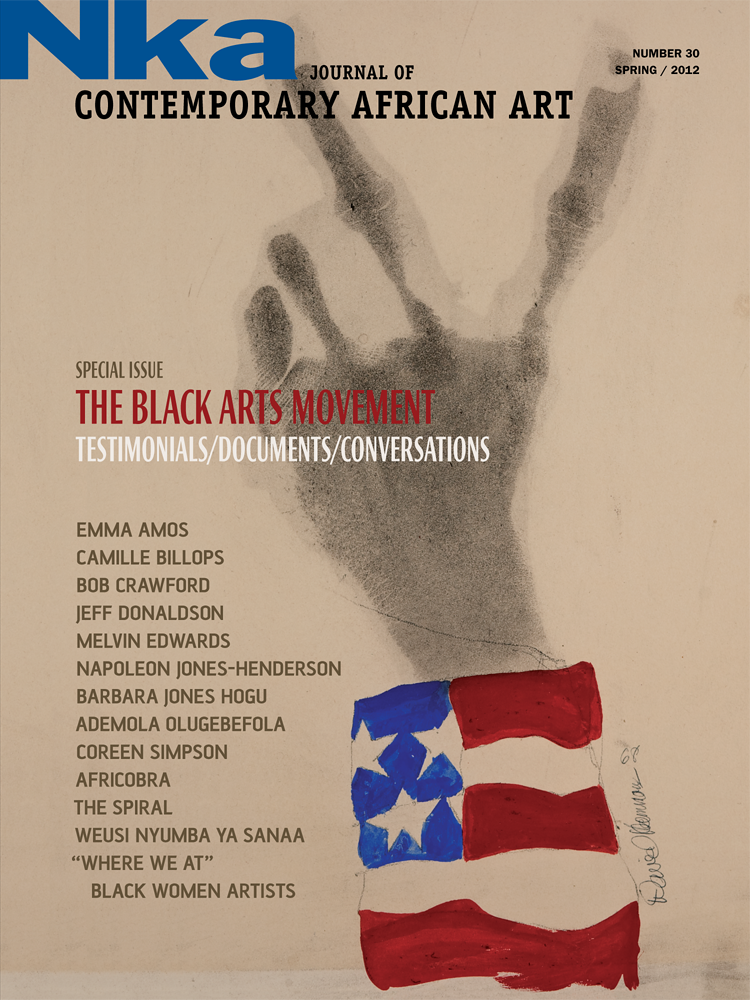

Nka Journal of Contemporary African Art, Number 30, Spring 2012.

There is, to my knowledge, no sustained study of African art exhibitions in New York City since 2004. It is also clear that petty rivalry, and competition within the profession, has only made it more difficult for those studying exhibition history to compile knowledge. It seems that only a few names are seen as truly deserving of the title of “curator” historically—to name a two: Pontus Hultén and Alfred Barr. The task of writing about recent exhibitions in a sustained manner is riddled with questions about curatorial merit. Some curators have outrightly dismissed studying this work; for example, when I curated an archival and bibliographic survey of Elvira Dyangani Ose’s curatorial contributions, titled “The Open Work,” at Bard College in 2021, Irit Rogoff accused me of advancing mere celebrity and implied that Ose’s work is unworthy of academic examination and notation.4 I have often been surprised by the suggestion, made by a few commentators, that Enwezor is the “only” curator of African art to speak of. Others are looked at as illegitimate: I was shocked when an artist dismissed University of Bayreuth alumna and Ugandan curator Martha Kazungu as “unknown” and therefore unworthy of writing the obituary of an internationally renowned Ugandan artist who had recently died.

One way to account for the last twenty years in African art exhibitions would be to, as Hegel did, apply stereotypes and clichés. His view was that Africa was ahistorical. We can fall prey to this cliché, or we can use this cliché strategically.5 In the 1980s, African art was by and large considered primitive or backward by the major metropolitan art institutions. The cliché that Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso took inspiration from West African masks continues to hold serious interest, even for Black artists who remain uncritical of African art’s definition as more or less a curiosity of the avant-garde.6 One might say, with evidence, that the focus on historical rather than contemporary African art and the attachment to its attendant clichés is merely due to the collection practices of modern art museums, with their emphasis on modernist art history. But I argue that the reverse is true. Since the 1980s, African artists of all kinds have been collected by Western institutions. Yet Spanish curator Octavio Zaya has argued that the rapid pace at which these artists have entered Western institutions has led to a flattening of their work in museum classification and narration according to regionalism. In 1997, Zaya wrote about the same phenomenon happening to Latin American artists in European art fairs and institutions. Aware of these critiques, I have argued that African art was viewed by leading modern art institutions as coherent and compact, perpetuating the idea that its display could rest purely on cliché without much research into the circumstances of its production or its historical specificity.7

In exhibition catalogs and in his rigorous curatorial research, Enwezor pushed back against clichés that Matisse and Picasso took for granted—that African art is compact, pliable, easy, coherent, and without history—as well as the more recent romance with Afro-pessimism. He drew from other African political rhetorical traditions, including those of Négritude, a movement that began in 1930s Paris and consisted primarily of poets and philosophers such as Léopold Sedar Senghor, Léon Gontran Damas, and Aimé Césaire. Later, this movement influenced the likes of Jean-Paul Sartre and Frantz Fanon, in effect intertwining African political rhetorical traditions with currents of existentialism and psychoanalytic theory. Post-Fanonian political theorists Amílcar Cabral and Kwame Nkrumah attempted to refine African Marxism and socialism through these strands of thought.

Négritude was one of the primary vehicles that shaped a new understanding of African art and aesthetic philosophy in the mid-twentieth century, and therefore contributed to the task of making African art legible on terms that were not compromised.8 Because of Enwezor’s training in political science, he understood the philosophical basis of these African political rhetorical traditions, and how to apply them to visual art. His 2002 PS1 exhibition “The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa, 1945–1994” conceptualized an alternate timeline of aesthetic modernism that coincided with liberation and independence movements. He carefully thought out a “postcolonial constellation” of art that intersected with lessons from Nkrumah, Cabral, Senghor, and others, applying their ideas to the task of transforming history. His bringing together of thought traditions from Europe and Africa was not unique, since Senghor, Nkrumah, Chinua Achebe, and Paulin Hountondji did same in their writing. His attempts to study aesthetic modernism from an alternative timeline followed a precedent set in African thought, especially by Senghor, who extended African political thought to modern and contemporary art.

When I teach Enwezor’s exhibitions in the classroom, I usually have students delve into the printed-matter archives of historic exhibitions from the 1990s or earlier.9 Students have often pointed out how misinformed these exhibitions were, particularly the exhibitions that received criticism for the display of stolen artifacts.10 After rigorous class discussion and study of museum research and acquisition policies, students have suggested that Enwezor was keen on repairing the broken-down museum policies that allowed stolen objects to be shown publicly or kept in their collections in the first place. That Enwezor was trying to repair the museum and its policies may appear shocking to some, given that, as mentioned earlier, exceptionalist and conservative historical thinking in academic and institutional circles prevents his work from being taken seriously, despite the widespread respect he enjoys.

Kader Attia, Reason’s Oxymorons, 2015. Photo: Blaise Adilon.

Looking at my list of thirty African art exhibitions over the last two decades in New York City, I see the impact of Enwezor’s thinking, particularly in exhibitions that focus their rhetorical weight on the politics of liberation or on a Fanonian account of psychoanalysis. Two shows come to mind: the 2012 New Museum Triennial, entitled “The Ungovernables” and curated by Eungie Joo and Ryan Inoue, who incorporated a postcolonial reading of “ungovernable” inspired by the Black Consciousness movement in South Africa; and Kader Attia’s exhibition “Reason’s Oxymorons” (2017) at Lehmann Maupin Gallery, which dealt with a postcolonial reading of psychoanalysis.

The New Museum show included artists such as Emeka Okereke, a documentary photographer who works in Lagos and Amsterdam; Nana Offoriata Ayim, a filmmaker and novelist who focuses on Ghana’s rich cultural history; Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, a painter who makes portraits from the imagination; Iman Issa, a sculptor from Cairo who conducts artistic research on historic objects and forms; Hassan Khan, a musician and conceptual artist also from Cairo; and Kemang Wa Lehulere, who makes drawings and sculptures that commemorate important historical events in South Africa. The notion of being “ungovernable” that the curatorial proposal relied on emerged from the Black Consciousness movement in South Africa during the 1970s and was made popular by the anti-apartheid struggle. Joo and Inoue’s press release affirmed this position without naming historical figures: “We will make this country ungovernable!” it said. I found an earlier citation of this statement in a 2008 article about former South African president Jacob Zuma’s court trial, which attributed it only to an unknown member of a protest group.11 In a review of “The Ungovernables,” art historian Arnaud Gerspacher wrote skeptically of the show’s borrowed concept: “These forms of ungovernability and the artist’s ‘holographic existence’ can equally describe terrorist strategies, something that amounts to an unthinkable occlusion of history.”12 This is to say that the concept has been removed from its historical context, taken as an aesthetic term rather than a tactic. I suspect that Gerspacher’s reading was accurate but nevertheless unfair about the decolonial politics the show relied upon.

Other critics viewed the exhibition positively, as an opportunity to learn about artists from around the world. If Gerspacher and other critics took seriously the politics of the exhibition, they did not uncover or write about its roots in the rhetorical approach of, among other figures, South African activist Steve Biko.13 This may have to do with how the “ungovernable” title came into being—how the curators’ citational practice was limited in its grasp of the range and tenor of Black Consciousness. In addition to African artists, the show featured the agit-art of the Propeller Group, a collective working in video and researching the link between myth and politics; Danh Vo, who showed his disembodied Statue of Liberty; and Cinthia Marcelle and Jonathas de Andrade, two artists who look beyond the metropole towards rural and working-class Brazil.

Cotter had this insight: “How ungovernable can artists be who have all, so to speak, attended the same global art school, studied under the same star teachers, from whom they learned to pitch their art however obliquely to one world market?”14 This question marked the critic’s dismissive attitude toward what the curators called the experience of “a generation who came of age in the aftermath of the independence and revolutionary movements.” Cotter and others overlooked Biko’s Black Consciousness movement and the African National Congress in favor of the excitingly brilliant aesthetics of the exhibition. Had this exhibition been curated by Enwezor, the critical response would have been different, and in fact more positive, as he had come to be accepted as the “only” curator of African art and therefore an authority. I know this because six years earlier, Cotter’s review of Enwezor’s “Snap Judgments” at the ICP museum took a completely different approach by actively repeating the curator’s Afro-pessimist analysis rather than flatly rejecting it.

Five years after the New Museum show, Kader Attia’s exhibition “Reason’s Oxymorons” was much more explicit in its presentation of the kind of political traditions focused on psychoanalytic theory and aesthetics that I mentioned earlier. Presenting sculptures that echoed the modernist aesthetics of Mondrian and Brancusi, its title artwork was a network of computer screens in office cubicles that almost filled up the first floor of the building, and which showed looped interviews with philosophers, healers, and psychiatrists. The work was, to this viewer, clearly referencing Martinican psychiatrist Fanon and his research in Algeria, such as his psychological study on the effects of the Algerian war on young soldiers, which constitutes many passages in his book The Wretched of the Earth. The video interviews covered topics ranging from magic and healing in African religions to the philosophy of Négritude. One of the interviewees in the video is the Senegalese philosopher Souleymane Bachir Diagne, who developed a rigorous study of Négritude.

Yet writer Andrew Stefan Weiner complained that Fanon himself was missing from the interviews of psychiatrists, philosophers, and shamans.15 It appears that Weiner favored the relatively legible modernist sculpture and its historic African sculpture references. “By and large, the other sculptures in the show successfully achieve the objectives they seem to set for themselves,” he wrote, but “it was strange to find hardly any discussion of Frantz Fanon.” Attia’s show reached for a complexity that absolutely defeated the trope that African art is easy and pliable, going instead for the dense and indecipherable. This strategy of opacity is rooted in rhetorical gestures that Senghor and Sartre deployed in their day. These psychoanalytic and strategic rhetorical gestures echoing earlier African political rhetoric were evidenced in both the New Museum and Lehmann Maupin shows. While these exhibitions were less successful in their rhetorical gestures—for instance, in how the New Museum show decontextualized Biko—the tendency in both exhibitions to work through African political rhetoric was particularly resonant with Enwezor’s earlier exhibitions like “The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa, 1945–1994” (2001).

2.

In 1997, Octavio Zaya—who would soon join Enwezor’s curatorial team for Documenta 11 in 2002—wrote an essay arguing that artists living in and/or born outside of Latin America could still be associated with the region despite long-standing curatorial mandates proposing the opposite.16 These mandates said that Latin American artists were only legitimate if they were born, living, and working in the region. Ironically, Adriano Pedrosa recently suggested that Enwezor was not a legitimate Global South curator because of his decades of residence in the United States and Germany.17 Zaya titled his essay “Transterritorial,” using an anthropology term to describe the changing geopolitical economic and social realities that caused displacement and migration at the time. Zaya wrote that the

same essentialist view led to the discriminatory decision of the ARCO Committee. For that Committee, the contemporary artistic production of Latin America is coherent, limited, and compact. In geographical terms, it is also supposedly isolated, and therefore, cannot be contaminated, even when the artistic production of Latin America is the result of confrontations, impositions, assimilations, grafts, and appropriations vis-à-vis the various indigenous and foreign cultures. For the Committee, what is produced outside that territory, even though it is the result of activities by those who were or are its inhabitants or their descendants, is not essentially “Latin American.”18

By addressing the transterritorial, Zaya objected to the essentialist view that artists shown in Latin American art exhibitions had to be physically based and working in Latin America. Revisiting his argument in my own writing, I have referred to the ways that artists outside of the colonial metropoles must relocate in order to then become “emerging” in Western art worlds.19 Their status as “exotic” others must precede their entry into the mainstream of art and its institutions. For me, art’s deterritorialization has much to do with imbalances in relations of art. Thus, art’s deterritorialization can be conceived alongside philosophers like Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, who developed the concept of deterritorialization in dialogue with Michel Foucault’s writings on power. My aim was never to bog down Zaya’s cultural kumbaya or even be pessimistic, but rather to connect imbalances in the relations of art to structures of power.

Zaya pointed to what happens when Latin American artists enter the sphere of the art market, particularly as this field of commerce interfaces with museums more generally. Zaya was aware that the positioning of Latin American Art within the art fairs of Europe would create a snowball effect in how this region’s art was displayed within European and American museums and further studied within universities. By arguing for a deterritorialized field of art, I argued against renaming creative practices under the banner of either “Latin America” or “Africa.” The rhetorical move of reducing them to geography/identity operates at the level of an original violence, if we follow Jacques Derrida, because it renders this art under new names despite its long duration in an alternative art circuit of the developing world. Effectively, this reinscribes the imbalance of relations in art. When we think about “Africa” as coherent and compact within the art field, it masks these power relations and capital flows that enable such a compact view to begin with, and overlooks the mechanisms that produce this coherence. Beyond metaphysical and ontological violence, there are consequences to whom or what gets picked as “representative” of the African continent.

What happens when “Africa” is not viewed as so coherent and compact? One example can be found in curatorial work that employs a nonlinear narrative of photography on the continent and a psychoanalytic reading of African archives. Enwezor’s show “Snap Judgements: New Positions in African Photography” (2006) at ICP focused on predominantly abstract and nonnarrative documentary photography. It harkened back to the show “In/Sight: African Photographers 1940 to the Present” (1996) at the Guggenheim Museum, in which Enwezor offered a vernacular understanding of studio photography, through a nonlinear construction of photography history guided by writings on critical anthropology and modernity. In the catalog for “In/Sight,” Enwezor (who cowrote an essay with Zaya) mainly modeled a theory of modernity that followed anthropologists like James Clifford.

Enwezor responded to the ontological challenge of making exhibitions about Africa by saying that modernity exists in the vernacular. He continued to work specifically through the vernacular and the archival, arguably inspired by the South African photographer Santu Mofokeng (1956–2020). Cotter’s review of “Snap Judgements” extended some of Zaya’s earlier critiques of the way European art fairs named and categorized exotic others from the Global South. He was attuned to Enwezor’s strategic use of the idea of play “with Africanness,” to “customize it, make it personal, avoid it, ignore it, bring it to the international table and take from that table, while building on the work of their predecessors.”20 These approaches to curating resisted easy clichés.

Enwezor looked to “re-story” Africa by following the example of Chinua Achebe. Achebe’s formulations on the “image of Africa” writ large as perilous and horrific enabled Enwezor to theorize Afro-pessimism. He analyzed Leni Riefenstahl’s fascistic photographs of Nubian people as the primary example of such images. “Afro-pessimism” is a term that emerged in economic analysis during the 1990s to imply that African economies would cease to develop, and which has since been taken up in Black studies to talk about the continuation of slavery today, for example, in the prison system.21 In Achebe’s 1980 essay on Joseph Conrad’s novel Heart of Darkness (1899), Achebe lambasted Conrad for his depiction of African people in the colonial era as obliging fools, and challenged the novelist on his knowledge of African life and interiority more broadly. Enwezor turned this towards an examination of photography. In an obituary for Achebe published in Artforum in 2013, Enwezor wrote that

in my own work as a writer, critic, and curator, Achebe’s critical example of re-storying Africa was enormously influential. I came to curating and to writing about art with the same fervent belief that modern and contemporary African art, and the creative vision of African artists, mattered in the mainstream narratives of our era’s art.22

3.

My list of thirty exhibitions of African art produced in New York since 2004 includes not only artists based on the continent, but also those who were born there and migrated to other locations, or who were born outside of the continent to African parents. According to the curatorial mandates at European art fairs that Zaya described in 1997, most of these artists would not even qualify as “African art,” and indeed their work is not often described in these terms. This applies to exhibitions by Julie Mehretu at the Whitney Museum (2021), Kapwani Kiwanga at the New Museum (2022), Kehinde Wiley at the Brooklyn Museum (2015), Wangechi Mutu at the New Museum (2022), Nicholas Moufarrege at the Queens Museum of Art (2019), Toyin Ojih Odutola at the Whitney Museum (2017), William Kentridge at MoMA (2010), John Akomfrah at the New Museum (2018), Bouchra Khalili at MoMA (2015), and Kayode Ojo at 52 Walker / David Zwirner (2024). Shows of artists predominantly based on the continent include El Anatsui at the Brooklyn Museum (2013), Tracey Rose at the Queens Museum (2023), and Fredéric Bruly Bouabré at MoMA (2022). Undoubtedly the presence of so many contemporary art shows is a shift from 1989, when Africanist scholars at the Arts Council of the African Studies Association were only then asking: “What are we going to do about contemporary African art?” John Povey asked this question at the time because he understood that more African contemporary art was being shown in Paris, London, and New York, even though critics, curators, and scholars paid little attention to it.

Some survey exhibitions have broken ground in other areas of art-historical research. Suheyla Takesh’s “Taking Shape: Abstraction from the Arab World, 1950s to 1980s” (Grey Art Gallery, NYU, 2020) contributed an interesting perspective to the debate on North African artists in modern painting by showing artists Mohammed Melehi, Ibrahim El-Salahi, and Mohammed Khadda. Although not included in my list because it did not take place in New York, “Art et Liberté: Rupture, War and Surrealism in Egypt, 1938–1948” at the Centre Pompidou (2017), curated by Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath at the invitation of Catherine David, focused on Egyptian surrealist painters like Ramses Younan. Similarly, Leslie King-Hammond and Lowery Stokes Sims’s exhibition “The Global Africa Project” (2010) at the Museum of Art and Design in New York brought a new perspective on the intersection of contemporary African design and visual art. These historical surveys have educated curators working in art’s mainstream, and have contributed valuable scholarship. The commercial gallery Skoto has presented mini-surveys of mid-century artists like El-Salahi and Uche Okeke in New York, and the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair has held court in the city since 2015.

Some shows were inspired by, or in dialogue with, the 1980s identity politics movement. The Brooklyn Museum and the Studio Museum in Harlem have often shown African artists. On my list of exhibitions over the last twenty years are Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s “Any Number of Preoccupations” (2010), which was accompanied by the scholarship of Okwui Enwezor, and Paul Mpagi Sepuya’s group show “Evidence of Accumulation” (2011), both at the Studio Museum in Harlem. There was the thematic group show “Global Feminisms” (2007) at the Brooklyn Museum, which included Tracey Rose and Ingrid Mwangi among others. The solo mini-survey exhibitions of Rotimi Fani-Kayode at Hales Gallery (2022) and the Artur Walther Collection (2012)—the latter accompanied by the scholarship of Kobena Mercer—remind us of the connection of African art to gay and feminist liberation. Gordon Robinchaux Gallery, clearly inspired by Black, women’s, and gay liberation movements, has showed Leilah Babirye in a 2022 solo exhibition, accompanied by a monograph.

Since Enwezor’s time, a new generation of African curators has emerged. Outside of the smash hits and blockbusters mentioned earlier, there have been a number of focused, concise exhibitions, including “States of Becoming” (2022), a group show focused on diaspora and memory curated by Fitsum Shebeshe at the Africa Center in collaboration with ICI. Oluremi C. Onabanjo has curated Lagos photographers at MoMA, and though outside of New York City, Amber Esseiva has curated numerous solo and group exhibitions dedicated to Black and African artists at the Institute for Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University. Other exhibitions have pushed the definition of group or thematic shows, including “Black Melancholia” (2022) curated by Nana Adusei-Poku, and “The Open Work” (2021) curated by myself, both at Bard College. Larry Ossei-Mensah has curated a number of similar exhibitions at smaller galleries and works professionally through his consultancy ArtNoir.

Contrary to Holland Cotter’s statement, there have been many exhibitions of African art since Enwezor’s 1996–2013 period in New York and elsewhere. In order to dismantle fantasies and clichés, such as the idea that African art is pliable, compact, or easy to summarize, some exhibitions have shown that valuable psychoanalytic and strategic tools can come from staging a dialogue between African political rhetorical traditions and Western discourses on art, culture, and philosophy. Gerspacher and Cotter saw this use of African political rhetoric as flawed when it didn’t come from Enwezor—when it came instead from, for example, Attia or Joo and Inoue. I argue that this attitude derives from the view that Enwezor is the only African art curator, which leads his work to be treated as an exception rather than a precedent.

Okwui Enwezor photographed by Oliver Mark, Kassel, 2002. License: CC BY-SA 4.0.

My response to Zaya’s view of the compact and coherent presentations of Latin American artists at European art fairs is to suggest that, rather than only an epistemic problem, lumping artists together under “African Art,” without clarifying what we mean by “Africa” or without doing significant research, is a problem of the imbalanced relations of art. The curators doing the lumping, such as Adriano Pedrosa, seem to be saying that some art can only be grasped through intense research, and some art can be grasped quite easily. I propose that we take seriously the ways that art and artists travel, and by not penalizing folks for arriving “late,” because they may have been known elsewhere for much longer.

The range of exhibitions of African art in New York City has been dizzying in subject matter, genre, medium, and curatorial approach, though many problems persist. It is not only that power relations are imbalanced, but that young curators continue to be treated as tokens, unknowns, or even as idiots. No profession thrives if it does not recognize any practitioners beyond its top two or three most famous. Moving forward, it is difficult to imagine that petty rivalries will abate. It seems unlikely that the racism (the unfair judgment of the work and experience of African curators) will go away. The trenchant pessimistic attitude that Africa will never develop its own museums is evidence of that. Prior to his death, Enwezor himself was foggy on the issue of whether to shift focus to exhibitions on the African continent, preferring to curate and write for institutions in Euro-America. Perhaps even he had difficulty avoiding how the evolutionary logic of racist pseudoscience has passed down a belief that some art is more developed than others—a legacy we still have to actively confront.

This statement was made by Holland Cotter during a talk at the Centre for Curatorial Studies, Bard College. Cotter was invited as a guest lecturer for an elective graduate seminar on “Contemporary African Art” in September 2021.

The second Black guest curator to organize an exhibition at the Guggenheim was Chaédria LaBouvier, with the Jean Michel Basquiat exhibition “Defacement” in 2019.

This inconclusive list includes at least twenty-three solo or group exhibitions in New York museums, including major surveys for artists like Kehinde Wiley, John Akomfrah, Tracey Rose, and Wangechi Mutu, among others. It includes six solo exhibitions at New York commercial galleries including Skoto, Perrotin, and Lehmann Maupin. The list includes work by curators such as Kevin Dumouchelle, Oluremi C. Onabanjo, Naomi Beckwith, Suheyla Takesh, Sohrab Mohebbi, Leslie-King Hammond, and Lowery Stokes Sims, among others.

This is based on a personal exchange between the curator and author via email concerning the exhibition “The Open Work.”

Hegel claimed that Africa had no history. “What we properly understand by Africa is the unhistorical, undeveloped spirit still caught in the conditions of mere nature, and which had to be presented here only as on the threshold of world history.” G. W. F. Hegel, Lectures in the Philosophy of History, trans. Ruben Alvarado (Wordbridge, 2017). I am also thinking of Maryse Condé’s interest in the deconstruction and reconstruction of stereotypes and clichés. See Dawn Fulton, Signs of Dissent: Maryse Condé and Postcolonial Criticism (University of Virginia Press, 2008).

In a 2024 public discussion between Arthur Jafa and Simone White, Jafa talked about African retentions before pivoting to a discussion of African art. His views diverged from White’s. See →.

Serubiri Moses, “Content Sharing and Mistranslation: On Global Aspirations and Local Infrastructures,” in Forces of Art: Perspectives from a Changing World, ed. Carin Kuoni et al. (Valiz, 2021).

Okwui Enwezor, “The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa, 1945–1994. An Introduction,” in The Short Century: Independence and Liberations Movements in Africa, 1945–1994, ed. Okwui Enwezor and Chinua Achebe (Prestel, 2001).

I have taught a full graduate seminar on Okwui Enwezor in the art history department at Hunter College, and have featured his exhibitions in a graduate seminar at Bard College and an undergraduate seminar at New York University. Here I am referring to graduate students in Hunter College’s art history department.

See Olabisi Silva, “Africa 95: Cultural Celebration or Colonialism?,” in Nka Journal of Contemporary African Art, no. 4 (1996).

“Before a Zuma court appearance in September 2008: ‘If you don’t leave Jacob Zuma alone we will make this country ungovernable …’, attributed to an unknown member of the protest group from the ANCYL outside the court as they burnt an effigy of Thabo Mbeki.” J. C. M. Venter and A. Duvehage, “The Polokwane Conference and South Africa’s Second Political Transition: Tentative Conclusions on Future Perspectives,” Koers 73, no 4 (2008) →.

Arnaud Gerspacher, “New Museum Triennial, ‘The Ungovernables,’” e-flux Criticism, March 17, 2012 →.

For a sustained reading of Steve “Bantu” Biko’s political writing and his contribution to the Black Consciousness movement in South Africa, see Tendayi Sithole, The Black Register (Polity Press, 2020); and T. Sithole, Steve Biko: Decolonial Meditations on Black Consciousness (Lexington, 2016).

Holland Cotter, “Quiet Disobedience,” New York Times, February 8, 2013.

Andrew Stefan Weiner, “Kader Attia’s ‘Reason’s Oxymorons,’” e-flux Criticism, February 28, 2017 →.

Octavio Zaya, “Transterritorial: The Spaces of Identity and the Diaspora,” Art Nexus, no. 25 (1997) →.

“I am the first Latin American curator to be appointed as an artistic director of the visual art sector of the Biennale. Though, I’m not the first curator from the Global South, because Okwui Enwezor was of course a curator before me. But I’m the first one actually living and based in the Global South.” See →.

Zaya, “Transterritorial.”

Moses, “Content Sharing and Mistranslation.”

Holland Cotter, “Nontraditional Angles on an Africa Seldom Exposed,” New York Times, March 21, 2006.

See Okwui Enwezor, “The Uses of Afro-Pessimism,” in Snap Judgements: New Positions in African Photography (ICP, 2006); and Kevin Okoth, “The Flatness of Blackness: Afro-Pessimism and the Erasure of Anti-Colonial Thought,” Salvage, January 16, 2020 →.

Okwui Enwezor, “Chinua Achebe,” Artforum 51, no. 10 (Summer 2013).