Like a lot of Tosh Basco’s work, the images I’m looking at on my phone seem to evade capture and demand physical presence. The other day Tosh sent me this fleet of photos documenting the series of new drawings that make up the current exhibition “Angels, Hand Dances and Prayers” at Company Gallery in New York. The exhibition gives a glimpse into a body of work that accompanies Tosh’s remarkable output of performance over the past decade but which has been less commonly seen. And the question of the seen and the unseen is a preoccupation here.

It is particularly poignant given the notoriety Tosh gathered over the past decade under the former moniker boychild, a magnetic persona widely referenced in pop culture and scholarly articles. Her movement-based performance practice is slippery, moving, and alive. Although it begins with a body, the work does not end there. Sometimes it may point to Tosh’s origin story as a kid in San Francisco who accessed performance via drag, but more often it is reaching outward towards the future—questioning the possibilities of communication and expanding space for those who engage with the work to do the same.

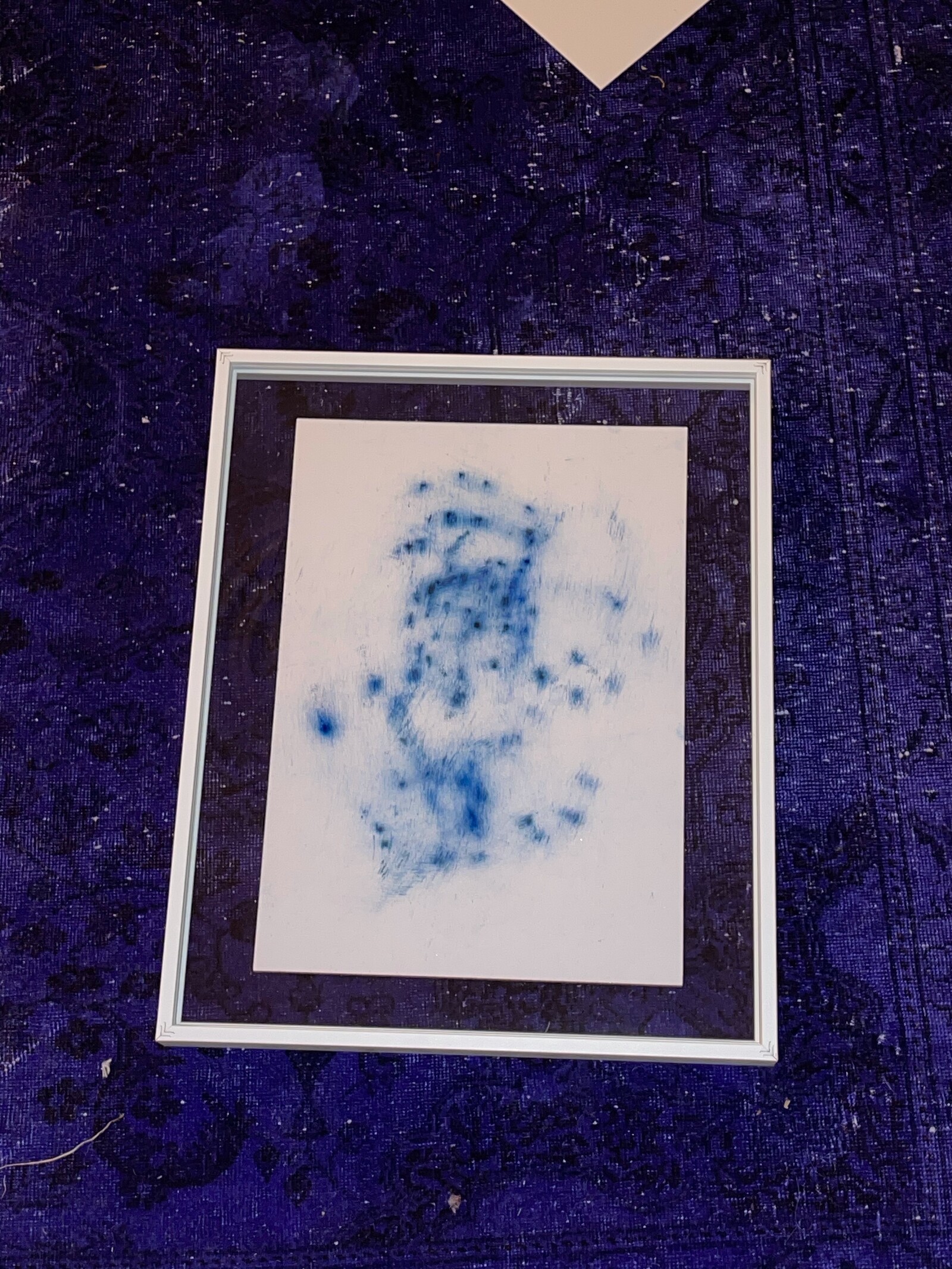

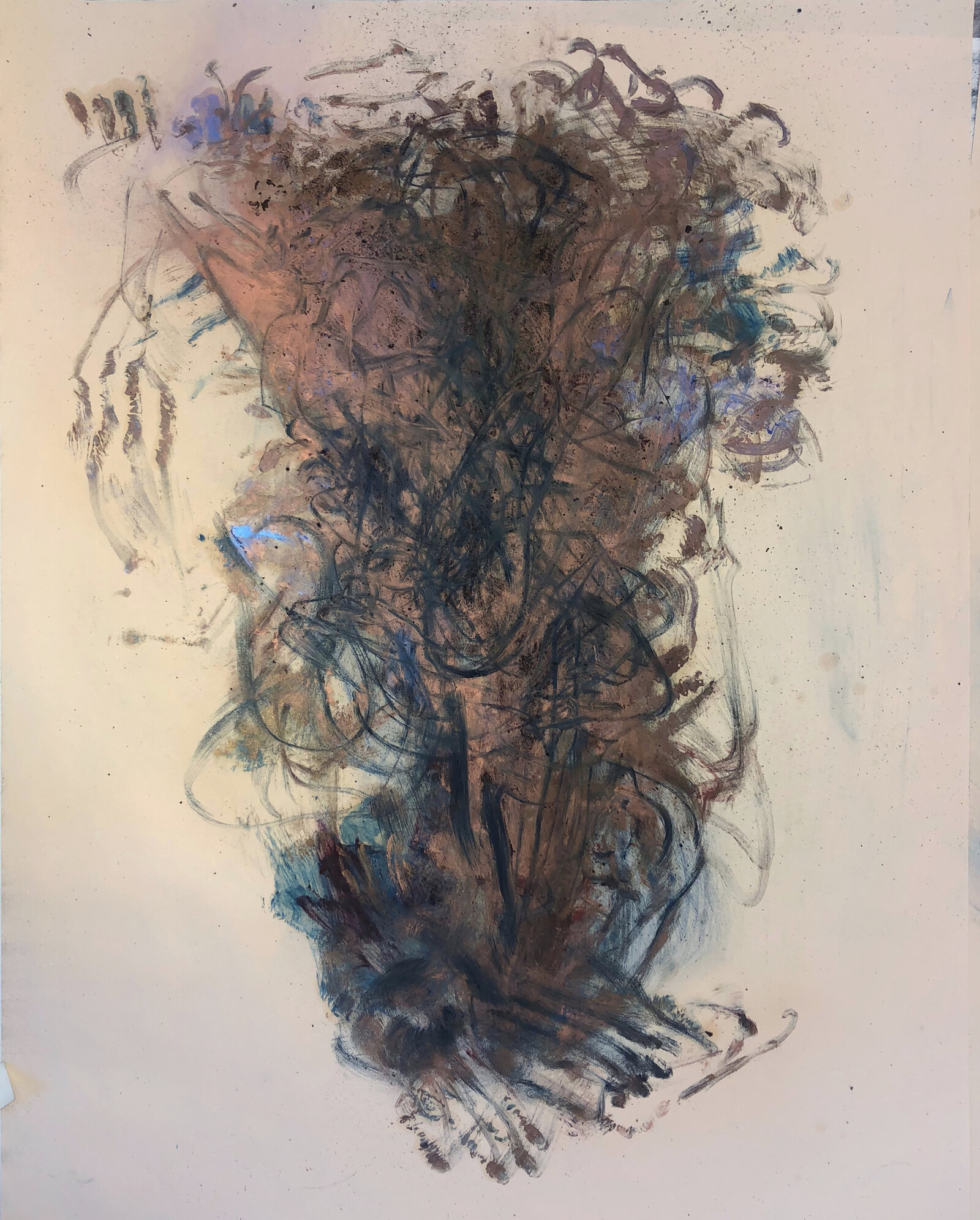

Tosh tells me the haunting drawings in “Angels, Hand Dances and Prayers” are all related to death and mortality. Yet I find them deeply moving and strangely alive. They show the stillness present in movements. I opened the jpgs one by one, zooming in on the astral bodies, impossible-to-grasp gestures. “Graphite are prayers,” “Blues are angels,” Tosh adds. I bleat in reply: “I wanna see these irl!” But in a pandemic and barring a miracle, there was no way I would get to see these “in body” any time soon. A few hours later my doorbell rang and a masked courier slipped a flat package to me. I opened it. And then I had a little cry. “What’s it called?” I asked. “untitled angel 4 safi.”

– Sophia Al-Maria

Sophia Al-Maria: Thank you for sending me an angel. It reminds me of those ghostly bird imprints on glass. So eerie. So beautiful. So painful for the bird, or I guess in this case, the celestial beings…

Tosh Basco: Ha. No angels were harmed in the making of these drawings.

SAM: Where do the angels come from?

TB: Everyone knows some kind of answer to that question. And that knowing acknowledges the answer is unutterable or ineffable.

SAM: Are they in reference to anything?

TB: They are definitely inspired by Simone Fattal’s angels, by the “angel of dust” Nathaniel Mackey addresses in Bedouin Hornbook (1986), Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus (1920), by the character named Angel that you wrote in the script for the film you’re working on, The Marina. I think as I encountered each of these references they became symbolic of a permission to acknowledge and further work through that-which-is-beyond common notions of “understanding.”

SAM: That reminds me of a word you and I have talked about, “to grok”: “To understand (something) intuitively or by empathy.” It’s a word from Robert A. Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land (1961), an old sci-fi book I’ve never read. Speaking of which, you are the only person I know who doesn’t just say they’ve read Samuel R. Delany’s Dhalgren (1975) but has actually read it several times. What brought you to that book in the first place and what keeps bringing you back to it?

TB: Dhalgren is one of my favorite books for many reasons, probably mostly because of the timing at which it arrived. For most of my adolescence I felt locked out of language. Somehow this book was an access point. The meandering of the main character, the Kid, and this fictional place ran parallel with the world I was experiencing at the time as a young person. All the edges touch on each other and open like a lascivious Klein bottle. That structure of continually folding is something that I relate to deeply in my practice, that everything is tangled up and touching somehow.

SAM: The last performance of yours I saw was Untitled Duet (the storm called progress) back in Berlin in January 2020. It was a durational piece you did with your collaborators Josh Johnson and Total Freedom (Ashland Mines) that lasted 10 hours split over two days. It had more than a touch of the mystic in it and had this epic proportion in the Gropius Bau. A spotlight searched the perimeter whenever you or Josh evaded it and the music was like a fucked-up medley of planetary hits from prehistory to now. Can you talk a little about the music in that piece?

TB: The piece was inspired by something Fred Moten talked about at Arika, a conference in Glasgow. He was talking about improvisation in relation to Benjamin’s famous obsession with Klee’s Angelus Novus and history’s storm blowing from paradise. So I asked Ashland to play us the storm, to reveal the wreckage of history through music, and I wanted to dance what it means to survive that wreckage with Josh. Ashland has always been somebody who grants us a certain access to a truth in music, its resonances, its possibilities. When I first started doing drag in 2012, I frequently performed to his twisted remixes. He has this beautiful capacity to simultaneously unlock terror and beauty. Untitled Duet (the storm called progress) used “time” as a grading force to be endured. The duration helped us attune to the weight of linear time as an imposition.

SAM: On a smaller scale, back in 2019 you performed a piece called Untitled Hand Dance at the Venice Biennale. To emerge out of the white wine-soaked and screeching maelstrom of the Arsenale and find you dancing alone in that oversize suit was really something. Even though it was performed in silence, it felt like a place to come and hear.

TB: I loved that location and chose it because of the ways in which being outside enunciates the impossibility of silence or stillness. White walls purport a false sense of neutrality that I wanted to be free of. And I feel grateful that you mention this about hearing. I’d always like my performances to offer alternative ways for people to understand the ways in which we “see” or “hear” the world around us.

SAM: I brought a friend along who was convinced you were in communication with djinn. I don’t know about demons, but that hand dance definitely communicated strongly to me without a single word. Can you talk a little about how you use (or don’t use) language?

TB: Language is the ghost that haunts me. I know now it can be danced with, that it is a tool, that it can be fluid, so the haunting is no longer attached to fear. Vaginal Davis once, very aptly, defined my movement practice as interpretive dance, and I don’t disagree with her. This is the part of my upbringing in the drag scene that can’t be taken away. I still use the lip sync as a kind of formula. Text(s) constitute a large aspect of the score.

SAM: Was the suit a reference to something? Is costume an important part of the process for you?

TB: The suit was a nod to Kazuo Ohno, one of the “founders” of the Japanese post-war movement forms called Butoh. The hand dance was inspired by him, Tatsumi Hijikata (the other founder of Butoh), and Ana Mendieta amongst many others. There are videos of Ohno dancing at a very old age in a chair in a tuxedo.1 He’s carried out by four people onto the stage. In his chair he dances even though his body is fixed in the seat. Costuming like lighting or makeup or camera lens (in a film shoot) are all there to facilitate the ways in which the audience member encounters the work. For me in this instance it brings forth references or contexts that otherwise can’t be explicitly shared.

SAM: Loving layering… your drawings do that too. They have an uncanny multi-dimensional quality similar to how your performances conjure up temporary alternate realities. I’ve been trying to figure out how you do this in the drawings and asked you the other day. In reply you sent Untitled (1969) by David Hammons and a few other examples of his “body prints.” His work is often talked about in a political context but when one interviewer asked if his art is political, he replied: “I don’t know. I don’t know what my work is. I have to wait and hear that from someone.” Do people ever do this with your work?

TB: Politicize it? I’m not sure… but I like Hammons’s response. I’m not sure what my work is, other than a bunch of questions.

SAM: What’s your relationship to performance and, more generally, the word or even idea of “live”?

TB: Well, I miss performing, I miss being with people. Somehow that word “live” makes me think of “death.” When the pandemic first started, we got to momentarily see all the stage lights of late capitalism turned off, and in that brief pause, certain mechanisms were revealed. The thing I love the most about improvisation is that it is “live” or ephemeral, that it seems in its nature to want to sift or move with and through time, bodies, people, rooms. Which is to say that I continue to stand by live performance as a medium to communicate through even if, for now, it is through its absence. Where does it begin or end in relation to reality?

SAM: That’s such a good question. Very The Matrix (1999)… do you have an answer?

TB: No… always only more questions. What are the daily rituals we are performing now that many usual pathways are closed? How do we perform care for others? How do we act as conduits for larger systems? How can performance allow us to reflect on the physical ramifications of decision or action?

SAM: That brings the quantum mechanics phrase “spooky action at a distance” up for me. I feel like I’ve heard you use that, and also you introduced me to Karen Barad’s writing about entanglement. Does physics feed into what you do?

TB: As much as it can, though I “understand” very little of it. Somehow I feel like I know things much more clearly through movement. Barad, Denise Ferreira da Silva, Fred Moten, and Fernando Zalamea have all given me language to map intricate, often invisible pathways.

SAM: There’s this really special video of a conversation you did in 2019 with Zalamea, who is a mathematician and philosopher, called “Borders between Mathematics, Gestures and Dance.” It was really striking because you spoke aloud into one of those headworn, pop star mics while you were performing. The description of the event was so great that I had to look it up again: “Fernando will share a gesture that sums up a mathematical concept with boychild. boychild will respond with a gesture of her own. They’ll then continue back and forth like this, maybe with some chatting.” The last line made me laugh.

TB: That was such a special “conversation.” Fernando’s math really holds me when I open flail and flay. Actually, to go back to Delany, there is something familiar in the way I encounter them both. I like back and forth. Life feels like an endless amount of touching, bouncing, seeping into (someone, something else) maybe with some chatting or dancing along the way.

SAM: Should we call this conversation “back and forth, maybe with some chatting…”?

TB: YES.

Tosh Basco’s “Angels, Hand Dances and Prayers” is on view at Company Gallery, New York, through May 29. A solo exhibition opens at Carlos/Ishikawa, London, on May 29 and runs through July 3.

Kazuo Ohno performing in Tokyo, 2002: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=retkrupRUqA.