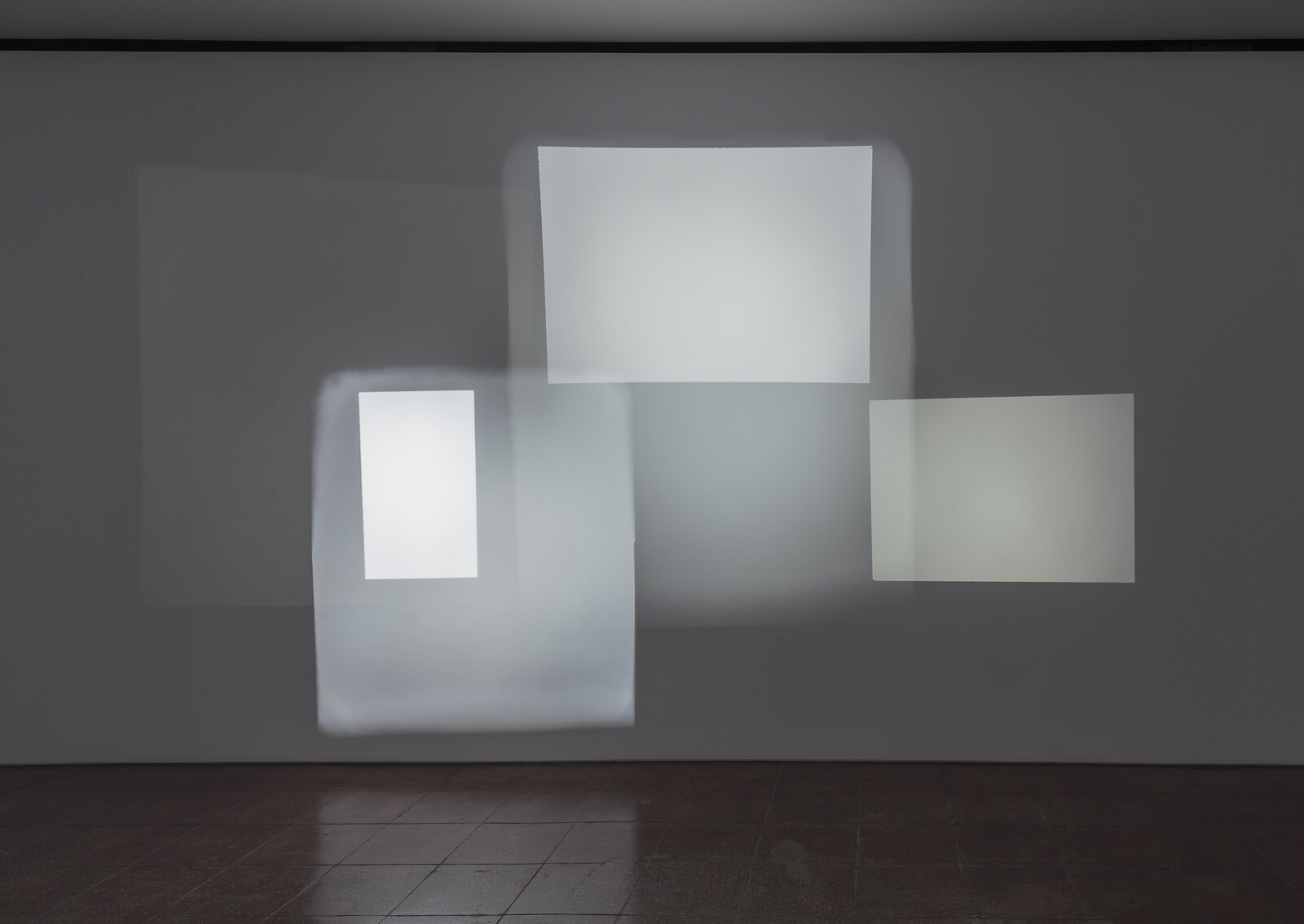

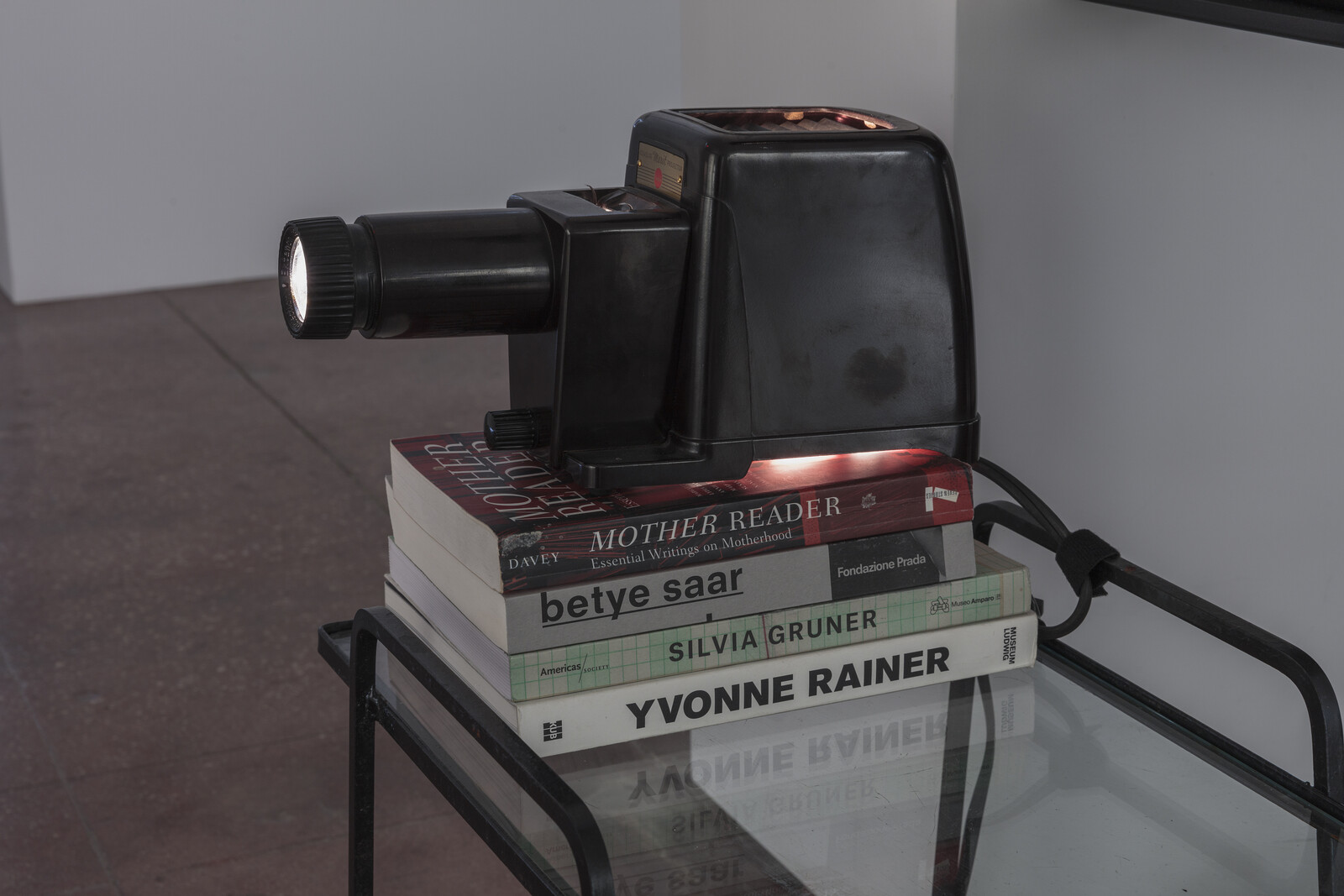

A series of slide projectors are supported by stacks of books and pieces of wooden furniture. The space is darkened, only illuminated by streams of light exuding from the projectors, as well as the images they produce: a range of abstract squares and rectangles in various shades of white that linger on the walls in a quiet rhythm. From a handful of speakers spread across the room, a recording is transmitted, with the sound of the artist’s voice, speaking English with a subtle German accent.

Titled Feeding the Ghost (2019), this multimedia installation is the centerpiece of Andrea Geyer’s current solo show at the Hales Gallery. The project was originally conceived as a performance lecture delivered by Geyer at Dia Art Foundation in September 2018. Indeed, this installation mimics the interior Geyer created at Dia, where she performed her lecture around an audience seated in the middle of the room, surrounded by small wooden classroom tables. The artist sat and read at each table for about 15 minutes, before switching to the next, while the audience’s gaze followed her, some awkwardly rotating their chairs. The text Geyer reads is always the same, an intimate account of her watching Chantal Akerman’s one-hour reading of A Family in Brussels, also delivered at Dia, in October 2001. Akerman’s text is a meditation on loss, written as a stream of consciousness in which her perspective is interwoven with her mother’s, a Polish Holocaust survivor who deeply informed Akerman’s work. Initially occupying the position of an observer recounting Akerman’s lecture, Geyer slowly starts weaving her own thoughts and experiences of loss through the text, describing what it was like to be in New York after 9/11. Thus, the speaking subject becomes increasingly muddled, as it rotates between Akerman, Akerman’s mother, and Geyer. This play on temporality, collapsing three speaking subjects into the present, taps into Akerman’s practice as a filmmaker; never adhering to linear narrative, she was instead interested in the past and present coexisting at the same time. Geyer, too, is invested in exploring how historical and social memory are constructed. Much like Akerman’s films, Geyer’s work cannot be quickly digested. One has to sit with it (or stand, in this case), and become comfortable with time’s passing—quite a challenge for those who live in New York.

Akerman’s rigorous commitment to frontal images, preferring structure over narrative, won her the label of a “minimalist” filmmaker, an association she did not necessarily approve of. Yet it is exactly these frontal images that are evoked by the slide projections, screens that show nothing but their own structure. Listening to Geyer’s reading while watching these flickering projections, the shapes gradually start to feel like apparitions, providing the ghostliness referenced in the work’s title. Who is this ghost? Surely, it must be Akerman, who haunts Geyer’s practice? Or could it be Akerman’s mother haunting the filmmaker, who committed suicide one year after her mother passed away? Or, is the ghost more abstract, evoking Jacques Derrida’s concept of hauntology, which proposes that the present is always haunted by the future and the past?

Feeding the Ghost is, above all, Geyer’s ode to Akerman—or rather, a eulogy. It offers an intimate dialogue between two queer women, a life within a life. In the same way that the protagonist in Akerman’s seminal 1975 film Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles engages with the space of her apartment after the loss of her husband, Geyer encourages her viewers to engage with the interior structure she has created, considering the extent to which an architecture can hold loss, the loss of Chantal Akerman.

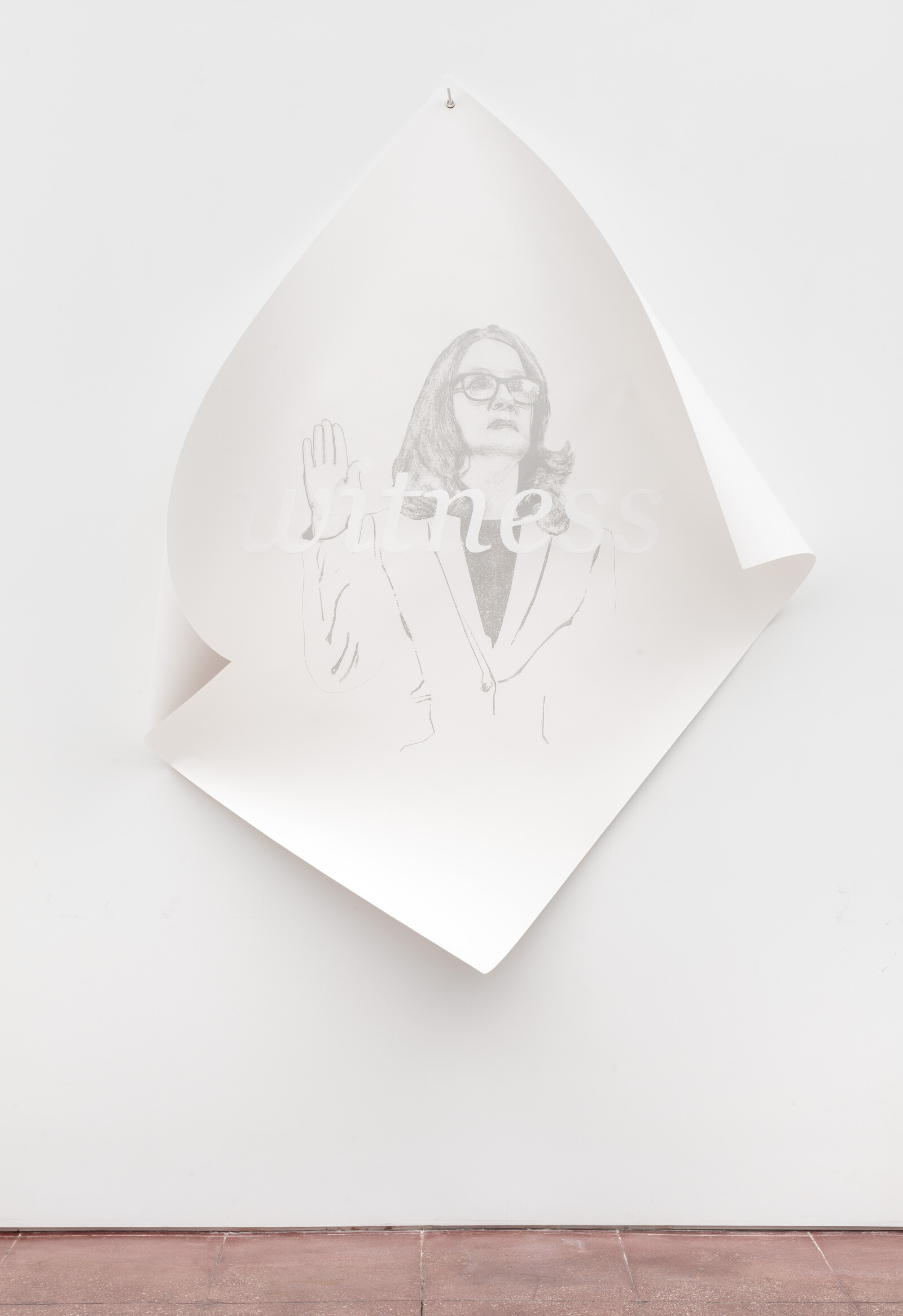

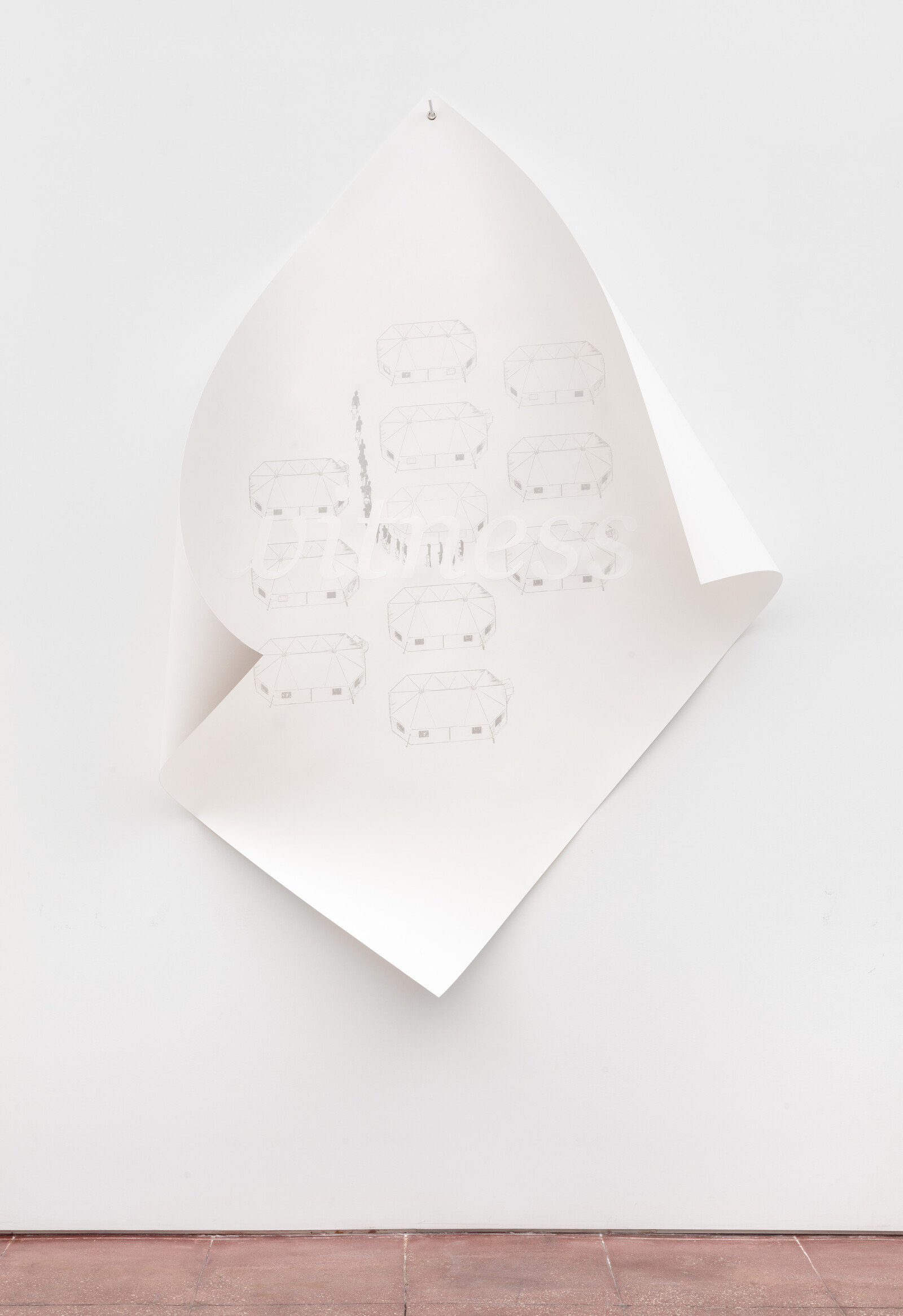

Two recent silkscreens, which give the exhibition its title, “On this day,” are easily overlooked. Hanging on separate walls in the back of the room, they are large, square sheets of white paper, the corners curling forward, their form and color echoing the slide projections. One of them, On this day (after Erin Schaff: Christine Blasey Ford testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee to address Dr. Blasey’s sexual assault allegation against the Supreme Court nominee Judge Brett Kavanaugh. September 27, 2018) (2019) is a portrait of Christine Blasey Ford, and reads “Witness.” The other, On this day (after Mike Blake: Immigrant children, many separated from their parents, are being housed in tents in Tornillo, Tex., near the Mexican border. June 2018) (2019) depicts 11 similar tents clustered together, with the “Witness” embossed in white in the center of the composition. Geyer’s intention is ambiguous. The most obvious interpretations are redundant indicators of political engagement that barely match the complexity of the artist’s practice. Perhaps the historical specificity of the depicted events is intended to call attention to the present, or rather make viewers aware that they are entangled in a historical continuum of trauma and injury. As Chantal Akerman’s films exemplify, the present is always haunted by the past, and marked by a promise to weigh on the future.