It’s fitting that “The Everted Capital,” the opening salvo of the second and third seasons of Fabien Giraud and Raphaël Siboni’s sweeping, unwieldy, and often exquisite magnum opus “The Unmanned”—a three-season series of films, sculptures, and performances—debuts at an end of the earth: the Museum of Old and New Art (Mona) in Hobart, Tasmania. Season one of “The Unmanned” limned an unorthodox history of computation via eight episodic film allegories, each representing a vital year in a reverse narrative from 2045 to 1542, and was shown and funded by several European and North American institutions over the course of its production, mostly recently in this exhibition’s first part at Mona earlier this year. “The Everted Capital” aims its sights on a subject no less vast: the history of capital. Mona not only debuts the work, but serves as its muse, patron, subject, and site. Carved into the subterranean sandstone rock of the River Derwent, Mona is as dazzling as it is idiosyncratic, a private museum built with (and partly to redeem) the online gambling winnings of its owner, David Walsh, and opened to the public in 2011 with Gatsbyesque West Egg benevolence. This November, Australia overtook Switzerland to become the country with the highest median adult wealth in the world, propelled by housing and mining booms indebted to aboriginal land.1

To reach Giraud and Siboni’s installation, visitors descend several stories to the museum’s lowest level, named The Void for its cavernous open space bounded by a soaring sandstone wall, which seeps liquid minerals as if gently weeping. It provides a luscious, dramatic scenography in which to sip an absinthe cocktail at the Void Bar. This seepage—a living, breathing, trickling inside the museum, whose de facto function is to preserve cultural and natural life by removing it from circulation and rendering it immobile—provided the starting point for the artists’ undertaking in Tasmania. They conjure the museum as a palace of salt, a material infinitely capable of yielding new and multiphasic mythologies and symbolisms, from salt poles as ancient currency to salt as conservation method. “Salt stops becoming,” Giraud explained to me, “it stops time.”

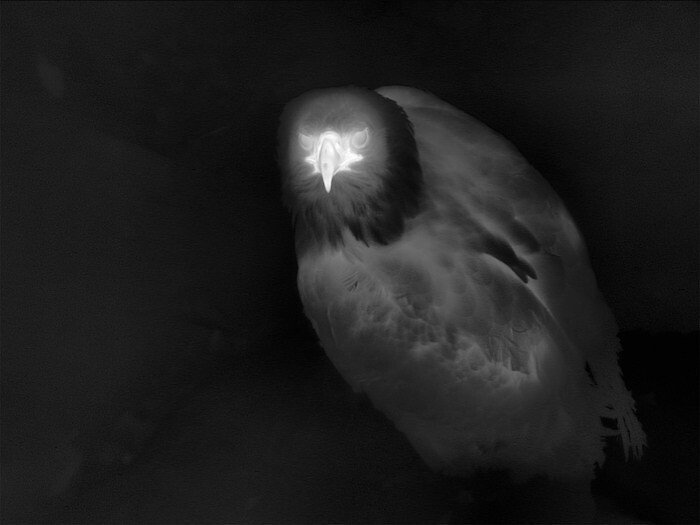

The first of the two-room installation is a small, darkened antechamber screening a single video, The Axiom (all works 2018). It functions as a prologue to the third season and to the installation that follows. The video’s lushness and acuity feel like natural extensions of the first season of “The Unmanned.” It is an extraordinary act of representation: a military-grade thermal imaging camera lingering with detached, robotic observation on various species of flora and fauna, their aliveness rendered ghostly white and luminescent. The audio brings to mind a heavy evening replete with throbbing insects, but there is no ground at all, because the work was filmed inside a custom-built sphere filled with materials used as forms of currency before the adoption of coins. The animals the artists have selected were also once currency—birds, lizards, even a beetle.

A hole torn in the wall leads to the main event, a large room with two primary components: a massive plinth scattered with a menagerie of sculptures and, at the back wall, a second, larger scale video, 7231. The plinth is a sculpture in its own right, shaped like a blade that narrows from a two-meter thickness to a fine point directed at visitors’ waist level. It was originally used as a dividing wall for the first installation, which the artists (not so) simply turned on its side to become a plinth for the sculptures, which slowly accrete crystallized salt, drip, and ooze. “Face Value,” a series of sculptures belonging to the third season, features cast faces—a nod to the Lydians, the first civilization to make currency depicting faces—based on masks from Mona’s collection. They rest on the plinth or are suspended by thick taut ropes tied to two facing columns, such that the plinth serves as a blade, slicing through the sculptures. But there’s also plastic tubing, chained fluorescent lighting, charred beams, and a large chunk of sandstone. Some elements work better than others, and the result is a sculptural excess that feels oddly inert, even banal (the plinth, while conceptually perfect, may be part of the problem). The best sculptures in the room, a suite of 24 sculpted blades designed by artificial intelligence, are nearly lost amid the detritus.

Something happened here. That something is the subject of the video, 7231, documentation of a 24-hour performance with 24 performers held at the museum, mostly in that same room, a few weeks earlier.2 It takes place in the titular year on a “Dyson sphere,” a vast structure built around our dying sun, and involves the performers collecting and trading salt before dying, one by one. Unlike The Axiom, the camerawork is shaky and handheld, recalling the forced and jagged intimacy of reality television, and the audio is equally punishing, high-pitched and relentless strings overlaid with drone-like narration by the children in the filmed performance. The entire space feels claustrophobic and anxious.

Giraud and Siboni strike me as deeply dialectical thinkers and makers, in the sense that they understand the world, or acts of worlding, as structured by series of diametric oppositions—but for the artists these purported oppositions are often two sides of the same coin. Thus, the two rooms of the installation are antipodes of each other, but they are also the same (everted?) thing, in that both present worlds with no ground (voids, again). Rather than the more typical dystopian fantasy of a future without humans, they propose another narrative. “What are we without the world?” they ask in the audio guide. “Just us humans without any ground to hold us.” They provide the minimal coordinates of this groundless world and, like novelists or puppet masters, set it into motion, waiting to witness what system of value might emerge.

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-11-23/australia-tops-median-wealth-per-adult-list/10518082.

The performance was not precisely 24 hours: its duration corresponded to the amount of time it took participants to complete the 24 tasks prescribed to them.