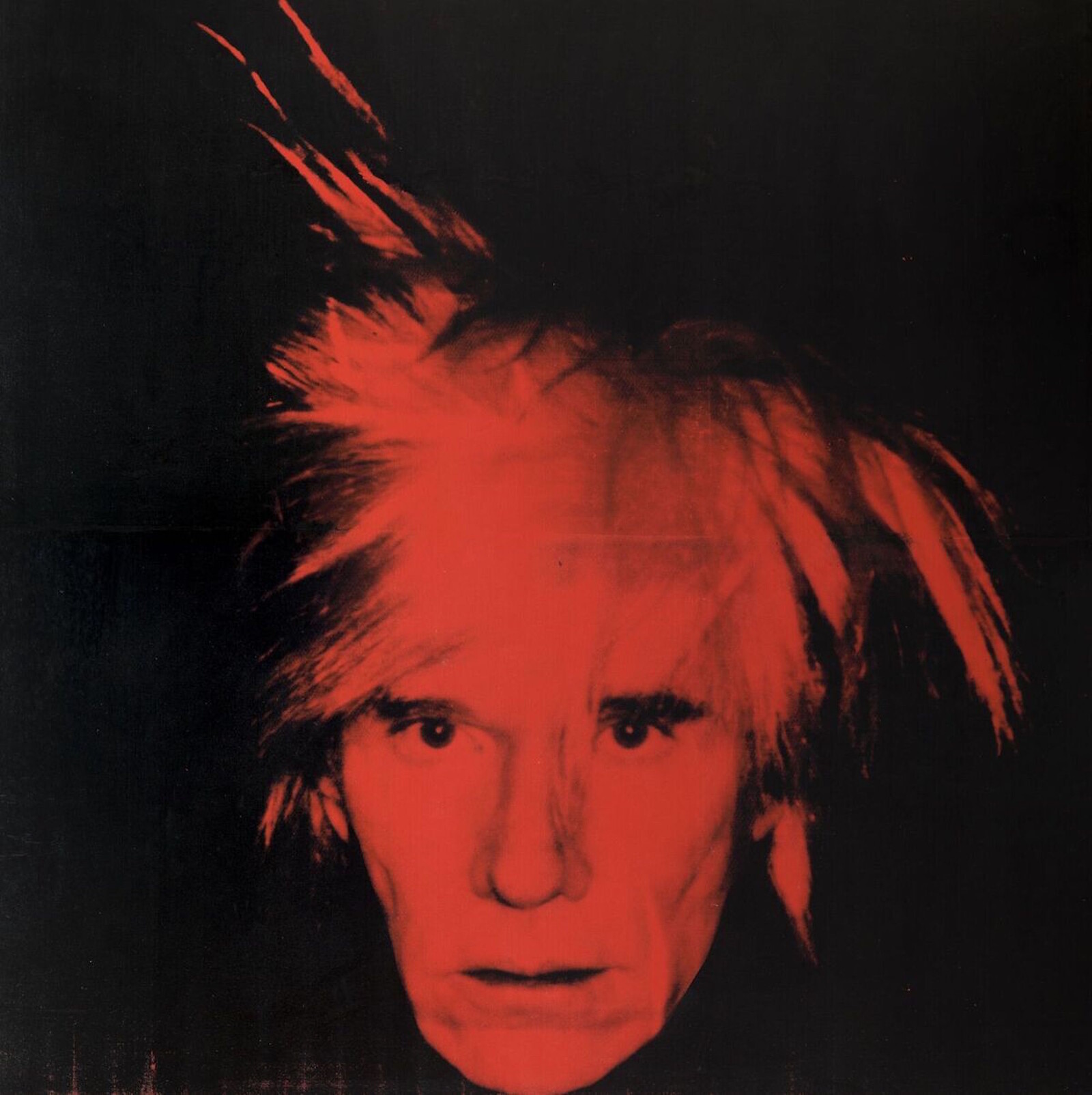

“The photo booth provided a safe-space for queer culture,” reads a text on the wall in the first room of Tate Modern’s 2020 Andy Warhol retrospective. How times have changed. Ten years ago, the museum’s exhibition “Pop Life: Art in a Material World” cast Warhol as business-bro godfather to Damian Hirst and Jeff Koons. That narrative has, thankfully, since gone out of fashion, and in its place a new Warhol has emerged: a shy, sensitive outsider fighting the good fight of representational politics on behalf of queer and minority communities in New York City.

Whether or not we prefer the idea of a woke Warhol, it’s almost impossible to square the language of the safe space with his back catalogue. “Warhol often used difficult imagery as source material, exposing the voyeurism inherent in media coverage of traumatic events,” Tate explains, attempting to exculpate their hero. Warhol may have been many things: talent scout, postmodern painter, an artist with a profound understanding of the currency of food, sex, and death. But what security did he extend to Olga Cassanova, the fourteen-year-old photographed falling to her death from an apartment block, whose final moments he reproduced in the screen print A Woman’s Suicide (1962)? To suggest that his relationship with the camera was motivated by an ethics of care, simply because he was queer, requires substantial historical revisionism.

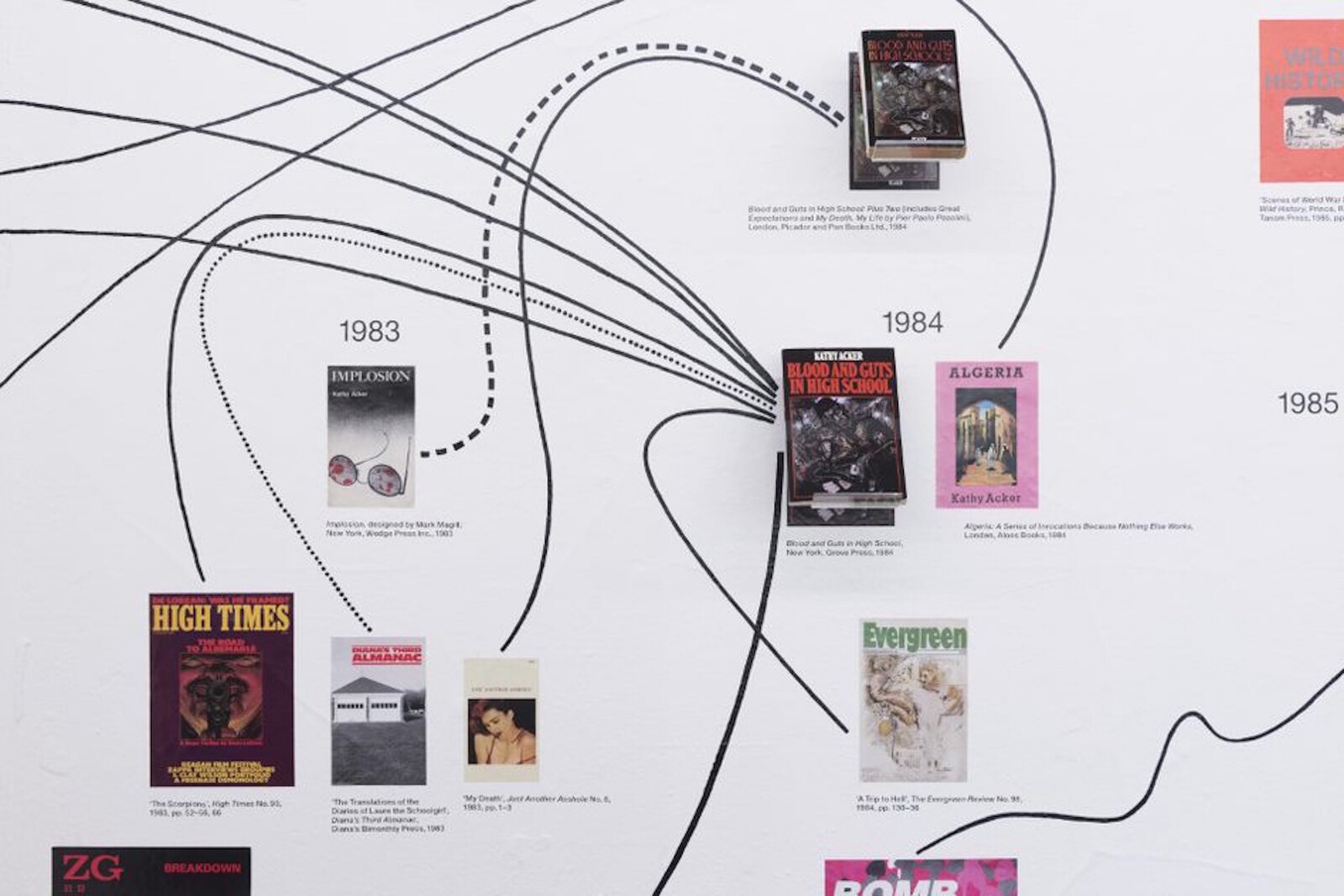

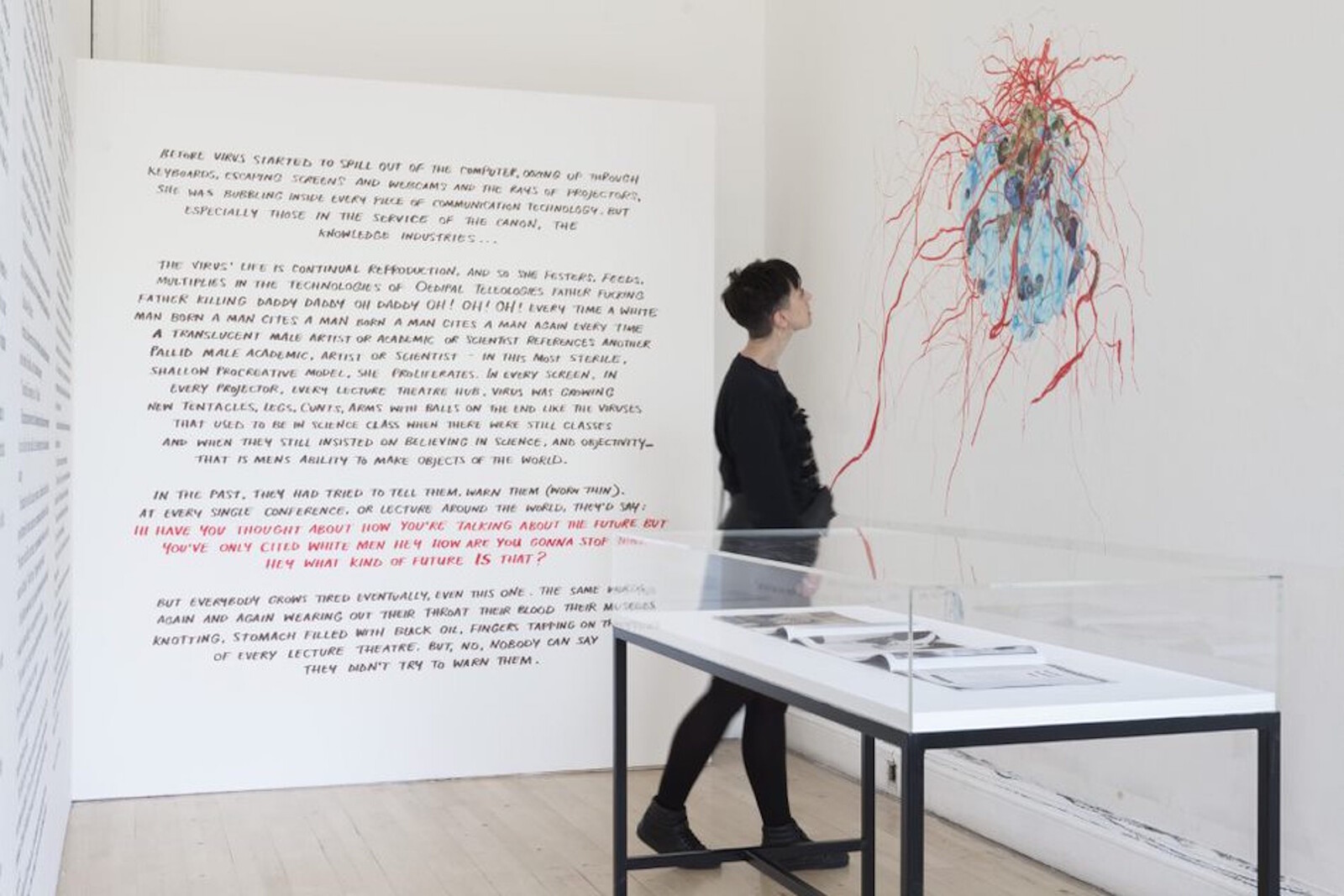

So why do it? Queerness, a movement committed to the disruption of entrenched power relations, is increasingly being used to secure the cultural establishment—one so intent on appearing compassionate that it is happy to ignore the obvious irony. Warhol is one of a number of figures who has been cleaned up and adapted to align with a vanilla interpretation of identity politics currently in vogue. Spare a thought for the overworked ghost of Virginia Woolf, raised frequently in recent years owing to the gender-switching protagonist of her novel Orlando: A Biography (1928). A 2018 exhibition at Charleston Farmhouse, “Orlando at the Present Time,” awkwardly positioned her as an intersectional icon and ancestor to contemporary artists including Zanele Muholi, whose photographic portraits of queer black South Africans were also on show. Awkward, because while Orlando may be an exceptional novel, it was written in protest at the fact that Woolf’s aristocratic lover, Vita Sackville-West, was barred from inheriting her family’s vast country estate owing to British laws of primogeniture. (Ergo, the very definition of a white, upper-class problem.) Kathy Acker, author of vociferously heterosexual literature, has also been given the treatment. The 2019 exhibition “I, I, I, I, I, I, I, Kathy Acker” at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, confusedly sought to position her as part of a queer avant-garde, by placing her work in relation to contemporary writers and artists including Caspar Heinemann, Jamie Crewe, and Isabel Waidner.

In order to make amends for very real histories of structural inequality, something akin to a moral code has been established among galleries and museums. This involves finding the marginalized more interesting than the powerful, embracing vulnerability and difference, declaring war against the concept of “normativity” and focusing on stories that have gone unheard. While the principles may be admirable, the overwhelming emphasis placed on the character of the artist has had troubling repercussions. In order to signal political alliance, an unfortunate tendency has emerged for back-projecting profiles onto ill-fitting figures.

When it comes to editing biographies in the name of political expedience, Barbican’s 2018 to ’19 exhibition “Modern Couples: Art, Intimacy and the Avant-garde” is a particularly striking example. The story of modern art was presented as a collection of short passages detailing relationships between key protagonists, the small selection of artworks on display providing scene-setting for the main event of biography. The Barbican also published a glossary of terms, including “Non-Binary,” for which Marcel Duchamp and his female alter-ego Rrose Sélavy were cited as the primary example. Duchamp posed for Man Ray as Sélavy, dressed in furs and a feathered hat, and attributed several texts and artworks to her. The queering of Duchamp was presumably done with the intention of making history a more inclusive and representative place for the living. In practice, equating non-binary identities with a work of performance art trivializes people who already frequently find themselves maligned and misunderstood. Barbican’s glossary represents the dominance of a depressingly limited form of hermeneutics that has come to define much of today’s critical discourse: interpreting art as a sincere and personal confession, and fetishizing the identity of the author to such an extent that what they make, and why they made it, is ignored. Duchamp’s alter-egos (of which there were many), much like his readymades, were part of a strategy to undermine the mythology surrounding the subjectivity of the artist, not to compound it. As Duchamp put it, “I was never interested in looking at myself in an aesthetic mirror. My intention was always to get away from myself, though I knew perfectly well that I was using myself.” 1

One reason queering art history has become such a popular pursuit is the openness of the concept itself. The current meaning attached to “queer” can be traced to a movement in early 1990s academia when US scholars including Judith Butler argued that sex was a cultural construction used to prop up heteropatriarchal societies; today it can mean anything from defying conventions of gender to identifying as an outsider to the status quo. Used as both a verb and a noun, the possibilities for its application are apparently endless. Where other identity brackets issue warnings to “stay-in-lane,” part of the utopian appeal of the queer moniker is the invitation to swerve across the road at will. This openness has spawned numerous institutional survey shows of “queer art,” and efforts to queer historical collections: “Trigger: Gender as a Tool and a Weapon” at New Museum, New York (2017–18), “Kiss My Genders” at Southbank Centre, London (2019), “The Other Gaze: Spaces of Difference” at the Prado, Madrid (2017), and “Queer British Art: 1861–1967” at Tate Britain, London (2017), to name a few.

Despite the promise of a radical, youthful cultural movement capable of shaking up the establishment, queerness has recently benefited the center ground: used to rejuvenate museum holdings, swell the ranks of academics (recent generations of whom have “queered” everything from Shakespeare to drone warfare), while also placing a burden of expectation on contemporary artists to constantly communicate their difference—a kind of ritual “outing” performed to a public who have been given the symbolic role of mum and dad. It’s also been adopted by the market. “Look at our top-performing artists—Andy Warhol, Francis Bacon, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, David Hockney,” contemporary art specialist Harrison Tenzer said in advance of the auction “Bent. Because Progress Is Never A Straight Line” at Sotheby’s New York in 2019, positioning queerness as just another sales pitch for the blue-chip. “So many of the moneymakers in [the contemporary art] department are queer artists.” 2 At this rate, queerness is in danger of suffering an accelerated version of the fate that did for camp. Once a coded social commentary that revealed the artifice of dominant forms of heterosexual culture, camp was swallowed by the commercial establishment for the manner in which it could make any product appear funnier, smarter, and sexier. “What does camp mean to you?” Anna Wintour was asked on the red carpet of “Camp: Notes on Fashion,” the theme for the 2019 Met Gala, and a frivolous take on Susan Sontag’s acutely sober essay “Notes on ‘Camp’” (1964). To which she replied, “Having fun!”

The frequent mobilization of the language of progressive politics disguises the reality that we are knee-deep in an era of cultural conservatism. The dominance of the canon is reaffirmed by making it appear more relevant to contemporary audiences; the lives and works of dead artists and writers sanitized and simplified in order to adhere to strict moral standards. In his essay Gay Betrayals (2009), Leo Bersani wrote of the pitfalls of twenty-first-century queer politics that “It seems at times as if we can no longer imagine anything more politically stimulating than to struggle for acceptance as good soldiers, good priests, and good parents.” 3 Within the arts, this has been extended to “good artists” and “good heritage.” Take a sweep of exhibitions across the past few years, and you could be forgiven for thinking all of art history can be queer, and all queers are angels.

When the artists McDermott & McGough opened The Oscar Wilde Temple in Greenwich Village in 2017, they went so far as to turn Oscar Wilde into a saint. The project moved to London’s Studio Voltaire in 2019, where the gallery was kitted out as a chapel, with a statue of the writer presiding over the altar, and paintings of his 1895 trial for buggery on the wall in which his head is framed with golden halos. Wilde’s literature was spiky, romantic, and laced with irony; he also had a taste for sex with teenage boys. Like many whose lives have been curtailed by the imposition of punitive regimes, wouldn’t his memory be better served by allowing him to be brilliant, but also complex and fallible—in other words, human? If there really is a will to make a more considerate art world, paying attention to what artists have to communicate, rather than what we might prefer them to think, feel, or represent, would surely be a better place to start.

Calvin Tomkins, Duchamp: A Biography (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2014).

James Tarmy, “Gay Art Auctions: Does the Label Help or Hurt an Artist’s Market?,” Bloomberg (21 June, 2019), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-06-21/gay-art-auctions-warhol-hujar-hockney-leibovitz-ritts-bacon.

Leo Bersani, Is The Rectum A Grave? and Other Essays (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010)