While exhibitions that question the modernist promise of progress are hardly new, a biennale that takes stock of the current state of regress raises high hopes. Historical regression is proceeding on several fronts. One is the collapse of the neoliberal faith in the end-of-history narrative—that liberal democracy and free trade economics triumphed over fascism and communism in 1989—as democracies across the West have embraced isolationist hard-right policies that indicate a return to fascism. Another is the resurgence of geopolitical antagonisms whose Manichaeism echoes the Cold War. Despite this golden opportunity for examination, “Pro-regress: Art in an Age of Historical Ambivalence,” curated by Cuauhtémoc Medina, María Belén Sáez de Ibarra, Yukie Kamiya, and Wang Weiwei, is a largely uninspiring reflection on our times.

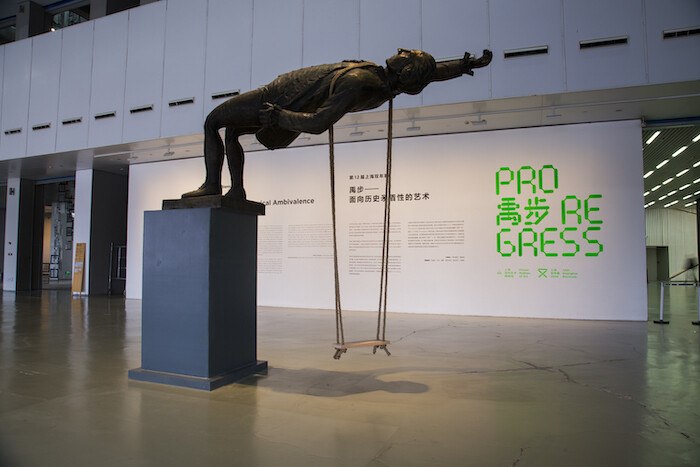

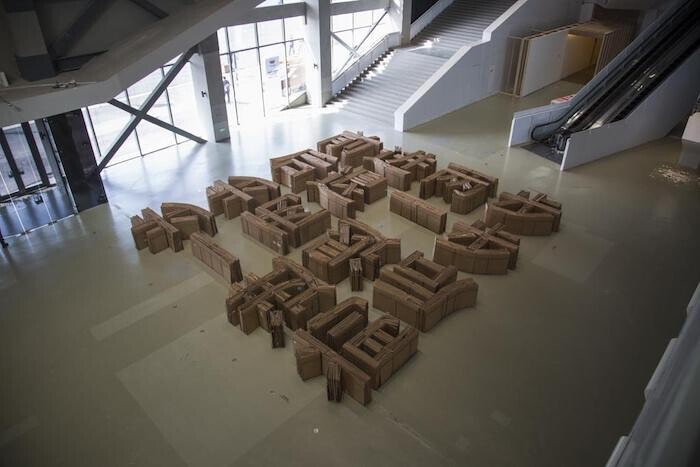

The biennale’s ambition, as indicated by its subtitle, is to reckon with “art in the age of historical ambivalence.” But the curators’ statement makes it clear that such ambivalence does not primarily pertain to current disillusionment, but rather to the stuttering back-and-forth movement of modernity in general. The premise thus echoes that of the 2015 Venice Biennale, curated by Okwui Enwezor, which posited global reality as “one of constant realignment, adjustment, recalibration, motility, shape-shifting.”1 One of the centerpieces at Shanghai—Enrique Ježik’s newly commissioned In Hemmed-In Ground (2018)—drives home this point quite literally. The work spells out the phrase “one step forward two steps back; two steps forward one step back” in knee-high Chinese characters made from bundled cardboard and arranged on the floor of the cavernous atrium of the Power Station of Art (PSA), mainland China’s first state-run contemporary art museum and the home to the biennale.

If this understanding of “historical ambivalence” is not general enough, the curatorial statement asserts that, while we admittedly “find emancipation and empowerment overtaken by despair as we witness the return of old forms of discrimination and obscurantism, there is no chapter of social transformation that has not raised an antagonistic formation.”2 Having steamrolled the complexity of the current moment into a universal, temporally unspecific struggle between good and bad, the statement goes on to enumerate examples of this dualistic worldview: feminism vs. misogyny, experimental family structures vs. social conservatism, the promise of technoscience vs. the dangers of climate change, and so on.

The exhibition is, in part, generic by necessity. (The biennale opened five days after Xi Jinping’s nationally broadcast visit to the China International Import Expo in Shanghai. The full artist list, meanwhile, was released only two days before the exhibition opened, further raising the specter of state control.) Yet another aspect of its superficiality—the dressing of political content in an aesthetic frock—is less excusable. The biennale gravitates toward artworks that purportedly deal with “urgencies” but casts those subjects in harmless—and, worse, ineffectual—aesthetic terms. The biennale’s Chinese title, “禹步” (Yubu, an ancient dance used in Daoist rituals), betrays its hand. According to the curators’ statement, Yubu symbolizes the constant movement of conflicted society and suggests “a creative coming and going of ideas, desires, and concepts.”3 The link between lofty aestheticism and grave reality—in this case forged not by substance but by the curators’ metaphorical imaginations—typifies a disappointingly large number of the works.

The extent to which this link depends upon wall labels for explication indicates that many pieces cannot speak for themselves. A selection of landscape paintings on wood and linen by Yishai Jusidman, taken from the larger series “Prussian Blue” (2010–16), render photographs of the locations of former Nazi concentration camps (such as Birkenau, Dachau, and Treblinka) in the titular shade of cyan. The wall label explains that this pigment is related to the Prussiac acid used in Nazi gas chambers, and that, “coincidentally, accidental stains that are chemically identical to Prussian blue remain to this day in some of those gas chambers.” In the 1960s, artists marshalled documentary techniques to deconstruct knowledge systems; in “Prussian Blue” and other works at the biennale, “coincidental” facts and “accidental” historical links can feel like overcompensations for a shortage of aesthetic means.

Another recurrent strategy that risks devolving into vapidity is the marriage of established techniques (namely collage, readymades, chance, seriality, industrial fabrication, and gestural brushstrokes) with hot topics (feminism, climate change, refugee crises). Voluspa Jarpa’s Monumenta (2018) shows strips of defaced archival documents from brutal foreign interventions in Latin America, bursting from a vertical series of cubes strongly reminiscent of Donald Judd’s work. It’s a document-monument of Cold War–era history that resonates with contemporary anxieties about surveillance and prompts viewers to dwell on the rather beautiful brushstrokes defacing the documents and those boxes. In constructing this monument of marvelous effects, however, Jarpa’s engagement with minimalism feels merely aesthetic, legible not as a continuation of an avant-garde project of formal reduction but as an art-historical token. Such tokenism blunts the critical bite of the work.

This criticism aside, Monumenta is troubling and powerful. Yet many other works at the biennale fail to provoke complex thoughts and instead pair borrowed aesthetics and superficial engagements with real-world concerns. Hsu Chia-Wei’s Black and White – Malayan Tapir (2018) is a case in point. Interspersed in a video of a zoo guide’s introduction to the Malayan tapir are related archival documents, which appear and disappear as the guide imparts information. Chia-Wei’s combination of computer-screen aesthetics with archival material points to the likely influence of Camille Henrot’s famous 2013 video Grosse Fatigue. Yet the appropriation of this aesthetic carries none of Henrot’s elliptical excess, and therefore fails to resonate with the themes implicit here—information overload, omnipresent screen-mediation, and so on. Rather, a wall text alleges, the work “hopes to apply an encyclopedic narrative to deal with the equality between people and non-humans.” It would be more meaningful were the author to actually concern himself with the extinction of rare animals.

There are, however, a small but encouraging number of meaningful works on display. Yuan Yuan’s series of paintings of expansive but derelict architectural structures “Bright Corners” (2014–18), for example, evokes the ambivalent temporality articulated in the biennale’s curatorial statement. For all their steely and monolithic materiality, these structures stand forlorn, seemingly anchored nowhere, both technological ruins and untrammeled musculature. That feeling of temporal adriftness is again captured in Hsu Che-Yu’s Lacuna (2018). The 40-minute video narrates two macabre happenings, which occurred during the artist’s youth in Taiwan, through the lens of family memories: the murder of a teenager at an internet café that the artist’s brother used to visit as an adolescent, and a remembered news report about a stray dog carrying a woman’s rotting, decapitated head in its mouth. Suturing figure drawings with moody background photographs in swooning animation, the artist mobilizes the sense of uncertainty and incompetence commonly shared by youngsters—myself included—in navigating a strange world.

While the social critiques prevalent in this biennale build upon the legacy of postwar avant-gardes, they are also a slap in the face of that legacy. The reliance on institutional framing—putting uninspiring work on a pedestal to make it “art”—is back with a vengeance. This is a biennale whose outlook on art, while superficially disavowing the primacy of aesthetics, remains romantically conservative—it is itself, ironically, regressive. As the apparently sincere beginning of the curatorial statement makes clear: “We not only assume that one of the tasks of the artist is to render his or her works with a certain ability to serve as oracles, but we also expect them to become omniscient objects in order to help us understand our own condition.” The “oracular,” “omniscient” art object is not only on a pedestal—quite anachronistically, it is on a throne.

Okwui Enwezor, “All the World’s Futures: Statement by the curator of the 56th International Art Exhibition,” https://universes.art/en/venice-biennale/2015/curatorial-statement/.

Curators’ statement by Cuauhtémoc Medina, María Belén Sáez de Ibarra, Yukie Kamiya, and Wang Weiwei, in the exhibition map for the 12th Shanghai Biennale, 3.

Ibid.