Johanna Hedva is a Korean-American writer and artist based in Los Angeles and Berlin whose practice traverses mysticism, music, and astrology, and the politics of illness, disability, and gender. They have relocated Ancient Greek dramas to feminized and queered contexts, and staged doom metal concerts informed by Korean shamanism; their essay “Sick Woman Theory”1 connects sickness and impairment with gender, class, and coloniality. Their practice encompasses performances, films, novels, music, readings, and installations: all these forms, in Hedva’s own words, “transforming into each other, trespassing.”2

In the summer of 2020, Hedva presented their first solo exhibition amidst the rubble of the Klosterruine Berlin. “God Is an Asphyxiating Black Sauce” showcased a decade of texts, songs, and performances, and audio versions of sections from their 2020 book, Minerva the Miscarriage of the Brain.3 The installation was designed to be accessible to all bodies: the Klosterruine was empty aside from red ramps, two speakers, and a series of benches, while the exhibition also took place on the website godsauce.black (with the sound pieces captioned and described) and across the city of Berlin.

I first met Hedva last year at the exhibition I co-curated with George Vasey at Wellcome Collection, Jo Spence & Oreet Ashery: Misbehaving Bodies. The following conversation forms part of our ongoing discussion of language, astrological readings, our literary heroines, and the way ancestral forces shape our fates and our bodies.

–Bárbara Rodríguez Muñoz

Bárbara Rodríguez Muñoz: I am at home in London, listening to your voice softening as you read excerpts from Minerva on godsauce.black. I remember telling you about my favorite podcast Between the Covers. In the latest episode, Lidia Yuknavitch defines corporeal writing as “writing from the body,” from the trauma located in its parts, their point of view. She claims that the stories that emerge have a different relation to language, beyond communication: they make it “strange.” For Motherload’s durational performance at CalArts you asked the performers to “read” your script with their bodies. How do you think this form of writing and reading affects the way you use language and narrative?

Johanna Hedva: I think Yuknavitch is right that the body speaks, that trauma in the body speaks—of course, joy and pleasure and fury and torpor speak too.

I talk about what I do as writing, no matter the genre, and I work with the definition that writing is simply language embodied. That means that screaming in a room is writing, dragging a hand through water is writing. I’m the kind of mystic who thinks transcendence happens within and because of the body.

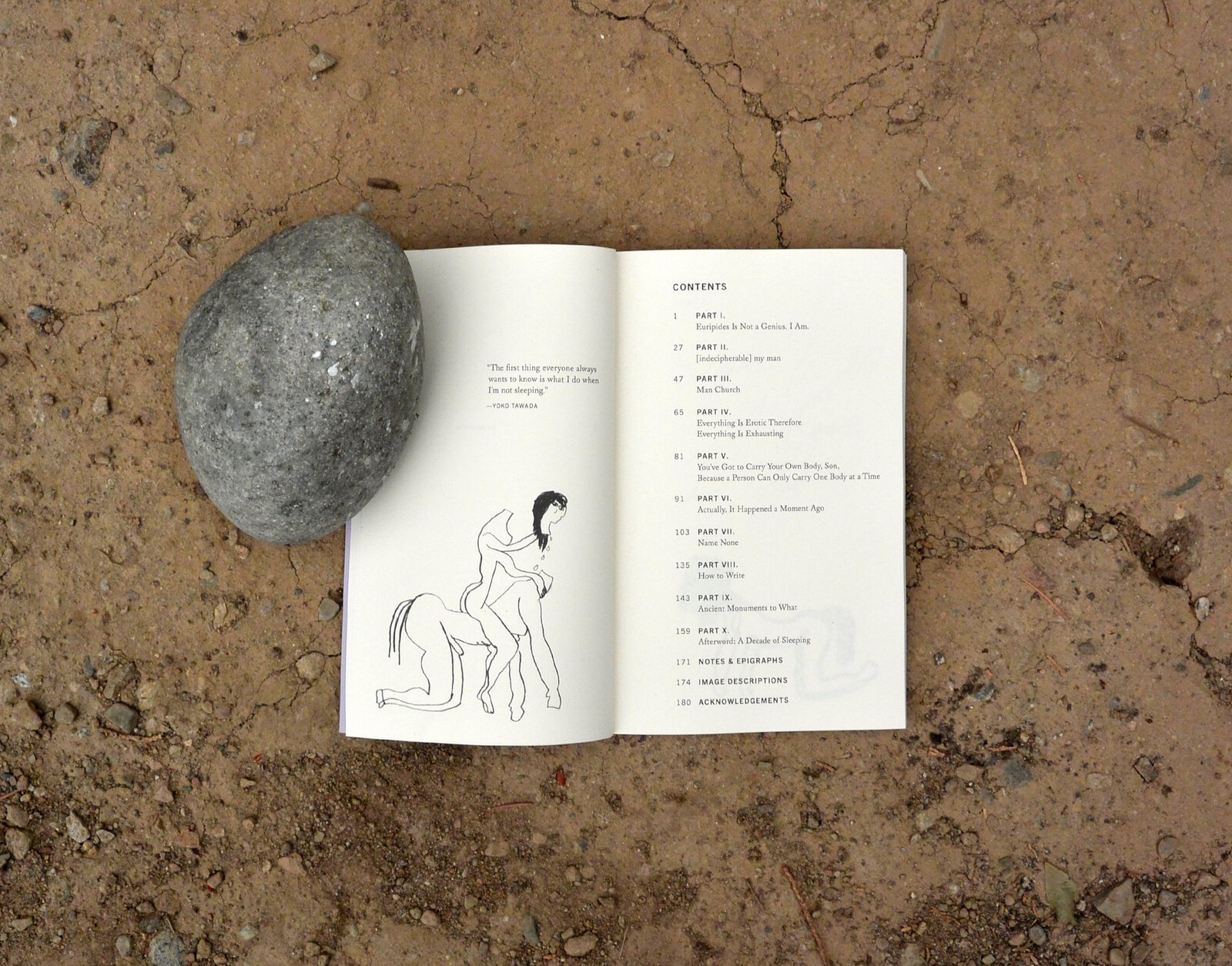

My work is promiscuous in terms of the different forms it takes, and the different worlds those forms live in (many of them trespass), and to me it’s this very shapeshifting-ness that is the crux of it all. It’s thinking of a novel as a concept album, or a manifesto as a stand-up comedy routine; it’s sneaking your political theory into an analysis on black holes. I spent a decade playing music in bands, and then I stopped for another decade to work primarily in performance art, but to me these were totally entangled, and now that I’ve returned to music, they are deeply imbricated with each other, it’s all cooking the same DNA. I studied graphic design for my B.A., and book and print design are huge parts of what I do—the font, the paper color, the visual layout, the body of the text, are all as important as the text itself. With typography you’re giving visual form to written language, with performance you’re giving it your own body. I guess I think of all these things as holding hands, which they do through writing—and of course, wherever there’s writing, there’s also reading.

BRM: I was struck by resonances between Minerva and “The Husband Stitch” by Carmen Maria Machado—a story about female subservience which blends together science fiction and folklore. In her new memoir, In The Dream House, Machado writes that “Places are never just places in a piece of writing […] Setting is not inert. It is activated by a point of view.” In Minerva, you describe the term “space” as an impossible concept; you also opt for the term “site-responsive” as opposed to “site-specific.” How did these ideas around absence and presence play out in your first solo show in Berlin?

JH: For most of my life I’ve been dominated by the conundrum of absence—I don’t think there is such a thing. Nothingness, emptiness, the void: these are all profoundly, viscerally present. They writhe and howl, they are HERE. I had an epiphany when I was young: I realized that, of all the art I’d encountered that had moved or changed me, the creators of these works would never know I existed. Most of them were dead, and there was no chance I’d ever meet the ones who were alive while I was alive. The epiphany was that this experience of vast solitude that I felt as an audience was something I’d also feel as an artist—but it wasn’t an encounter with absence. It was something sorcerous and magical, a force that insisted on presence.

When I first went to the Klosterruine, I felt huge presences—history, ghosts, the weather—at this site of 13th-century ruins that is one of the oldest structures in Berlin. I also thought of the pandemic: how many people would not be able to physically attend the show. I thought of how presence can happen without a body—how much of the world we can’t see or hear or measure, but which is still there. And when we talk about absence, what are we talking about? Does memory have a body, a form, a presence? I think it does.

BRM: It is remarkable how the pandemic has exposed ableism in the art world. As lockdowns started, many arts institutions rapidly shifted their programs towards online audiences and allowed staff and artists to work remotely and more flexibly, something for which disabled and chronically ill artists and cultural workers have been campaigning for decades. Yet accessibility procedures—simple tools such as captioning—are still not widespread, and as institutions reopen, few programs are attempting to connect physical and virtual experiences to allow for remote and meaningful engagements. Similar demands on physical presence shape politics and activism, as you explain in Sick Woman Theory.

JH: Yes, the world’s ableism has really risen to the occasion of Covid-19, hasn’t it.

I’ve recently been thinking of troubling this absence/presence binary in terms of disability access. Accessibility is a host for considering how bodies can be in public space, and if not, why. It’s structural, it’s political. It speaks to how we value certain bodies over others. And for me these days, in Covid-19, it’s a way to think about how we value presence, what we make it mean; and vice versa, how we value, or de-value, absence. There are many kinds of bodies that society prefers to make absent from its public spaces—but they are not gone. Absence is always political, because it gets directly to the Arendtian idea that one must first appear in public before one can be political. But what about the incarcerated, institutionalized, hospitalized, the ones who can’t leave their homes, the disappeared?

BRM: Your astrology practice is also political, challenging coloniality and ableism by “offering tools for articulation towards radical self-acceptance and healing.”

JH: The term “radical self-acceptance” gets bandied about a lot, but I’m not talking about using astrology to make you feel good about yourself. I’m talking about starting with doom as a beginning rather than an end, about learning how to surrender to your own decay, about accepting the great maw of the void that depletes you certainly, and which will of course eventually eat you. That kind of thing.

The kind of astrology I practice is greatly informed by the Hellenistic tradition, which was the kind practiced in the Roman Empire—but I am as critical of it as I am formed by it. Hellenistic astrology is essentially a colonial project: the Greeks took it from the Persian, Arabic, Egyptian, and Babylonian astrologers. But what I like about this old astrology is that it does not fuck around and, specifically, it predates the invention of the psychology of the self. Rather, it believes in fate: astrology’s raw material is fate, and the craft of it is trying to give this material form. In that way, astrology is a kind of writing. I use it as a storytelling device. You tell the future as you tell a story as you tell time as you tell me your name. Through astrology I’ve come to think about all forms of writing as forms of divination.

Over the years, I think I’ve become known in my community as the astrologer you come to when shit gets really bad and you need to hear what’s what without any prevarication or denial or trying to make it feel good. Like, you come to me if you have some of the scariest, devastating signatures or transits, stuff that would have made the Ancients pray for you. My approach is not for everyone: my readings are hardcore, we go deep. I work with people over a series of months (I do an in-depth written question and answer period, and then I read via audio recordings) and it won’t work if you’re not willing to really tunnel down into that dirt that is primary to who you are. I see the trauma in the chart first, I kind of specialize in it. Astrology is very good at giving language to experiences that contemporary society tends to consolidate under just one meaning. For example, the axis of illness and suffering is also the axis of ritual and care and sanctuary and sleep. There are three houses called the “trauma houses”—and these are also called the “mystic houses.” I have most of my planets on this crip axis, and in the trauma/mystic houses, so perhaps I have a special pull toward these places and the kinds of experiences, the kinds of lives and strife and knowledges, they produce. To me it’s not about concatenating them, but about allowing for all the specific and varied ways they can be articulated.

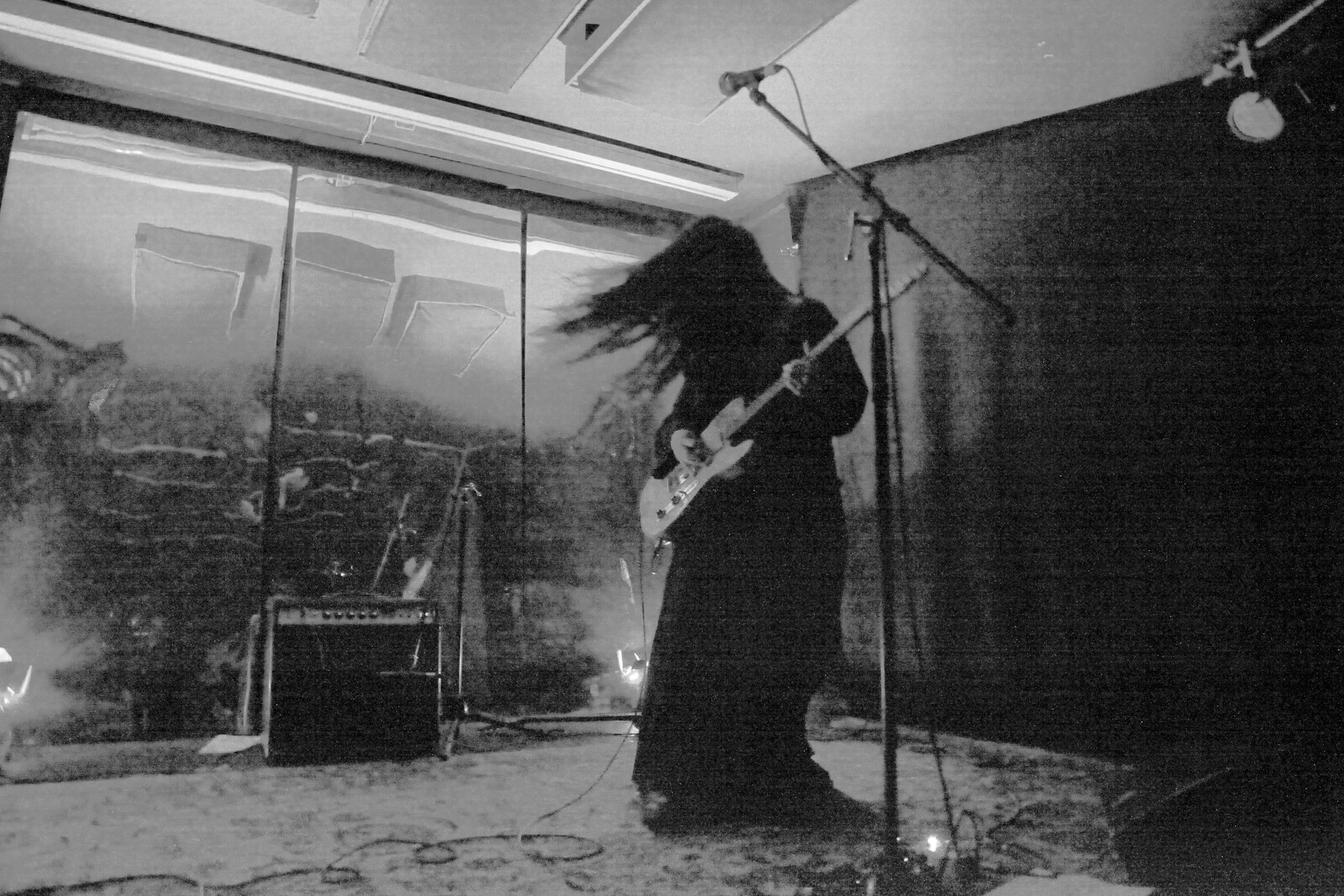

BRM: Earlier this year you performed Black Moon Lilith in Pisces in the 4th House at Wellcome Collection (which marked the first time we had metal music and whisky in the museum). This performance—which will be released on vinyl, cassette, and digitally in January 2021—is a grief ritual for your mother. I experienced it as a cathartic space between rage and love, absence and presence: you were there, intimately present, yet at some point I felt as though your body had left the room, allowing space for others.

JH: Black Moon Lilith in Pisces in the 4th House came to me—a rescue, a vortex—in the wake of my mother’s death in 2018. I could do nothing else but play the guitar and sing, which I hadn’t done in a decade, but I’d never played this way before, never sung like this. I started taking opera lessons after never having taken a singing lesson in my life. I started studying the Korean tradition of P’ansori singing, which is virtually the opposite of opera: in opera, the singer goes to great lengths not to damage the voice, but in P’ansori, the value is placed on making the voice as ravaged as possible. They are antipodes, and Black Moon Lilith demanded that I swing between them.

I wanted my guitar to match this duality—I needed it to sound like a demon and also like a kind of angelic bell—so I set about modifying a guitar that had come to me in a cursed way. That’s a long story. (Suffice to say that the person who originally gave me the guitar is someone I hope never to see again because if I did I would have only violence to offer him.) I changed every single thing on this guitar except for the body, customizing it with all kinds of specific, rare gear. Its cursed provenance helped Black Moon Lilith tremendously, because in each performance, I attack this guitar and violate it: we are not friends, but two voices that are battling each other and trying to sing in a kind of desperate harmony. We keep searching to find each other in the dark. It’s like I’m wrestling with the curse itself, the nature of cursed-ness at all. On the tour, everything has gone wrong with this fucking guitar—it got itself lost on three different flights; it broke in the middle of a show in Copenhagen. But it sounds fucking colossal when I need a brutal doom wall, it meets and matches my screaming, and it sounds tiny and clear and pure for the ballads. It takes me into the underworld every time—it’s perfect.

The narrative arc of Black Moon Lilith is one of encountering death. After the Wellcome show, someone told me that it’s really hard to make a performance as pure as this. I felt zapped when I heard that, seen. Someone else told me that the piece’s purity is “confrontational.” It’s just me up there, and I have only this one guitar and my own voice as my tools, or my weapons. It goes from the initial rage and violence of meeting death to the wash of grief, all the tears and heaving feelings that it brings, to a small, little crying-out in the dark, to, finally, not acceptance, but surrender to the annihilation of it.

For the audience, it should not be easy to witness, both in concept and affect. It should demand attention, be an entire world from beginning to end that eclipses you. It should scare you but feel good, like it’s cleaning you out. It should be a heavy blanket of darkness that is comforting, like the way a blanket can be too heavy but also be what you want. In a line, it’s about the labor of death.

BRM: What does it mean for you to have Black Moon Lilith in the 4th house of your chart?

JH: Black Moon Lilith is an asteroid that has been theorized to represent the place in your chart where you will be most injured by the patriarchy, and therefore, if you can cathart it, you will feel the most emancipation around this place. Mine is in the 4th House, the House of Home, Family, Childhood, Ancestry. It’s in Pisces, and it conjuncts my mother’s Sun. My mother was monstrous, spectral, terrifying, unhinged, broken—she was a witch. I can’t really talk about her here, except to say that my Black Moon Lilith being bound to hers is exactly right.

Emily Watlington, “The Artist who writes in their sleep” in Art in America, July 2020 https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/interviews/johanna-hedva-writes-in-their-sleep-1202695388/.

God is an Asphyxiating Black Sauce, Klosterruine Berlin, 2020. Curated by Christopher Weickenmeier. Black Moon Lilith in Pisces in the 4th House is coming out on crystalline morphologies (January 2021), a small independent label run by Gabie Strong, who started it to give a home to women and queer and TGNC people in the experimental music scene. Gabie Strong is partnering with Vivian Sming to release it. Minerva the Miscarriage of the Brain is published by Sming Sming Books.