At the heart of Mike Nelson’s Hayward Gallery retrospective is a wooden workbench. Chained to it is a series of Halloween masks: Frankenstein’s monster, the wolfman, a few scary clowns. The bench is embedded in a dense web of steel mesh that sprawls through the gallery, the haze of mesh dotted at points with concrete heads on hooks that bear bugged-out eyelids and gurning teeth, evidently made using the masks as casts. Studio Apparatus for Kunsthalle Münster (2014) is the high concluding point of this exhibition of Nelson’s detailed and ominous theatrical installations, fully occupying its Brutalist surroundings, as well as providing a concise summation of his work. After wandering through the creepy maze of The Deliverance and The Patience (2001), banging open dozens of doors and dodging other visitors in order to inspect each cramped room lined with cryptic clues—a pantheistic altar in one, a worn-down travel office in another—the sense of being a detective, on the hunt for the whys and whats, is heavy in the dusty air. The masks feel like a tacit acknowledgement of the roles we’re meant to play here: we’re not just any detective, we’re a B-movie detective, pursuing these ready-to-wear cinematic monsters through their weirdo burrows. These familiar tropes of genre film atmosphere, its dry ice-induced hazes and swooning synths implied, supply the narrative texture of Nelson’s work.

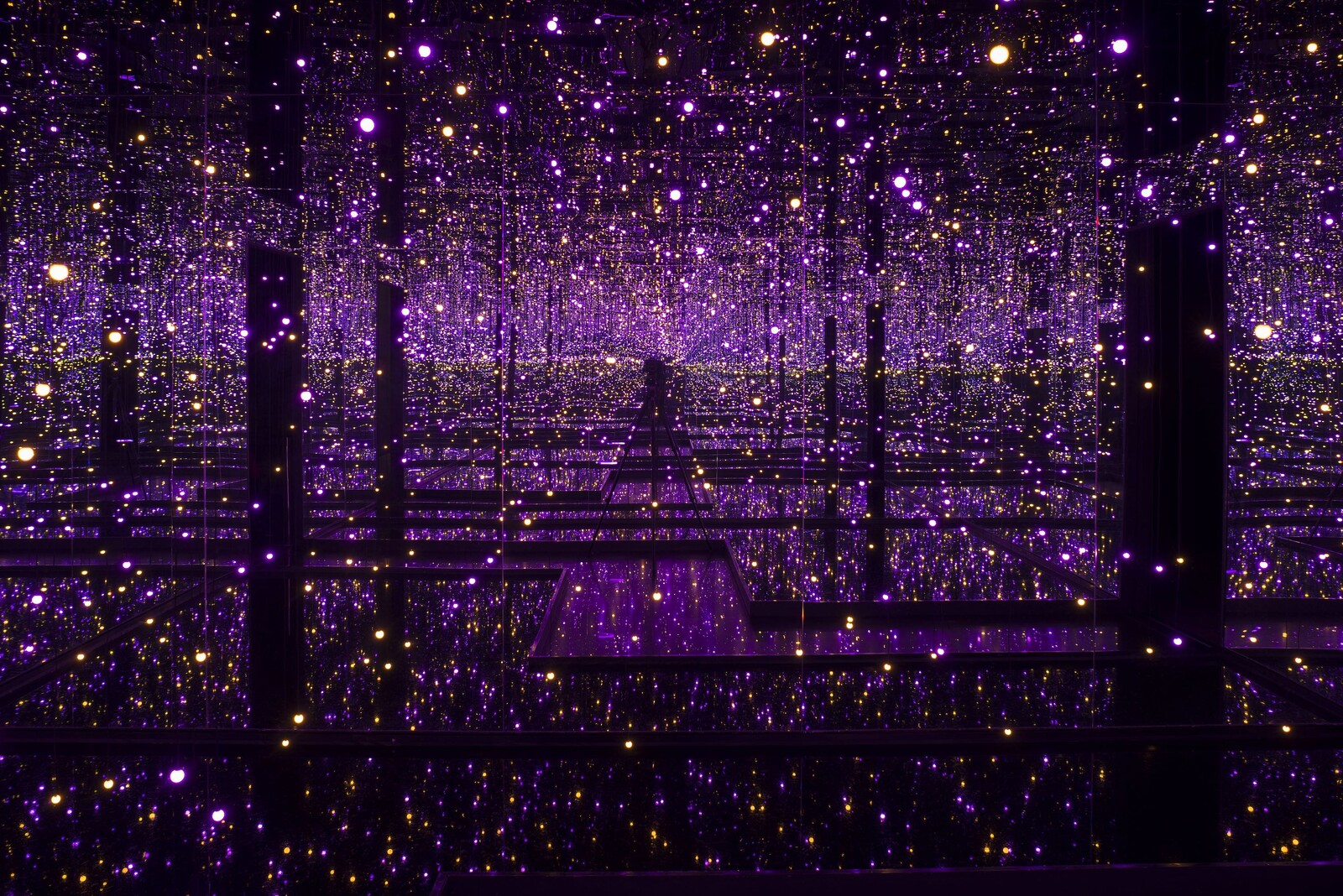

The archetypes invoked are relevant to the slew of “immersive” shows across London this spring, and as a perpetual feature, nowadays, of the art landscape—from Nelson, to Yayoi Kusama’s infinity rooms at Tate Modern, to R.I.P. Germain at the ICA, Richard Mosse at 180 Strand, the 360-projections of David Hockney, “Dalí Cybernetics”, and “Van Gogh: The Immersive Experience,” as well as any number of VR works across the city. These are wildly disparate forms of art, with varying levels of intent, from the unabashed fandom cash-cows of shows like the Dalí, which promise heightened access to elusive masterpieces, while shows like the Nelson and Germain ask for a little more intellectual engagement. But this one little adjective, “immersive,” seems to function across various media with a common dramatic purpose. Our invitation to be part of the work isn’t an innocent exchange; each asks us to inhabit a character. In Germain’s installation, where parts of the gallery have been turned into a grow room or a mocked-up bling jewelry shop, we’re shoppers, browsing for aspects of Black British culture; in Mosse’s ultra-wide-screen film Broken Spectre (2022), we’re tourists with the gift of flight, able to witness from above the destruction of the Amazon; at the Van Gogh Experience, in a warehouse stuffed to the brim with bad printouts of his self-portraits, we’re cast as devoted cult followers of the artist, visiting a mad funhouse dedicated to immortalizing his youth, complete with giant, totemistic sculptures of his head and excerpts of his diary being piped out over swelling, symphonic music.

The immersive will ask many things; mostly for you to remain awed, and not to look too closely. At one point in Mosse’s Broken Spectre, we follow a trio of cowboys trotting down a dirt path through thick forest. Hokey, idealistic twangy music helps them sashay along (stereotype is always ready to hand in the immersive; the more familiar, the easier for you to submerge). The scene isn’t notable so much for its sixty-five-foot-wide shot or its narrative impact (as an easy set-up for these down-home folks to be revealed as rainforest-decimators); more for the inch-wide projector overlap seam that runs straight through the center of this symmetrical oversized image, a pale line that cuts one rider off from the other two. The box of the Van Gogh “Experience”—where ten projectors cover the four walls and floor with swirling animations that set anything not pinned down in the Dutch painter’s landscapes aflutter—features a similarly impressive twelve-foot high seam in the middle of one wall, the place where a painting has been made to meet its own extremities.

In cinema, the idea of the suture always seemed, to me, like a handily visceral way to refer to the way alternating perspectival shots might bind the viewer into the space of the film; a surgical trick to forget the illusion of the cut. In the immersive, the suture is left exposed, to embody all that is willingly ignored here: the immersive is not a convincing illusion, it is not defined by its technical precision. The immersive seems to be defined instead by its other common properties: long, dark corridors punctuated with large, dramatically lit spaces; a centering of moving image (whether literally, as in most cases; or, like with Nelson, conceptually); an obsession with audience regulation and metrics (timed entries, queues, locked rooms, all guided by persistent invigilators).

The carrying principle is that immersion is the ideal state of audienceship; one that combines aspects of the voyeurism of cinema, the literal metaphors of installation art, the roving landscapes of gaming, the perspectival pics-or-it-didn’t-happen of social media, and of course borrowing a heavy chunk of script from the predetermined interactions of “immersive” theater. A hundred years ago, natural history museums were under increasing pressure to adapt their way of working, to translate their research into more audience-friendly displays that would “aggressively integrate scientific content, appealing display and educational interpretation.”1 Over several decades, the shifts towards interactivity and appeals towards non-specialized knowledge would result in the transformation from the “natural history museum” to the “science center.” The immersive is just an indication that a parallel shift is now underway for art institutions. It suggests a quiet reconfiguration of the axis along which art is disseminated, displayed, and appreciated, sidestepping concerns of media, of movements, of history. Art of any era can be drawn into this vortex: imagine the whorls of starlight of Van Gogh’s Starry Night (1889) animated as giant turning pinwheels, or the paintings of Hilma af Klint set in a VR spiral-shaped building. Any image could be set as a scene or cast large, to allow submersion in the new sublime of the perpetually animated immersive landscape.

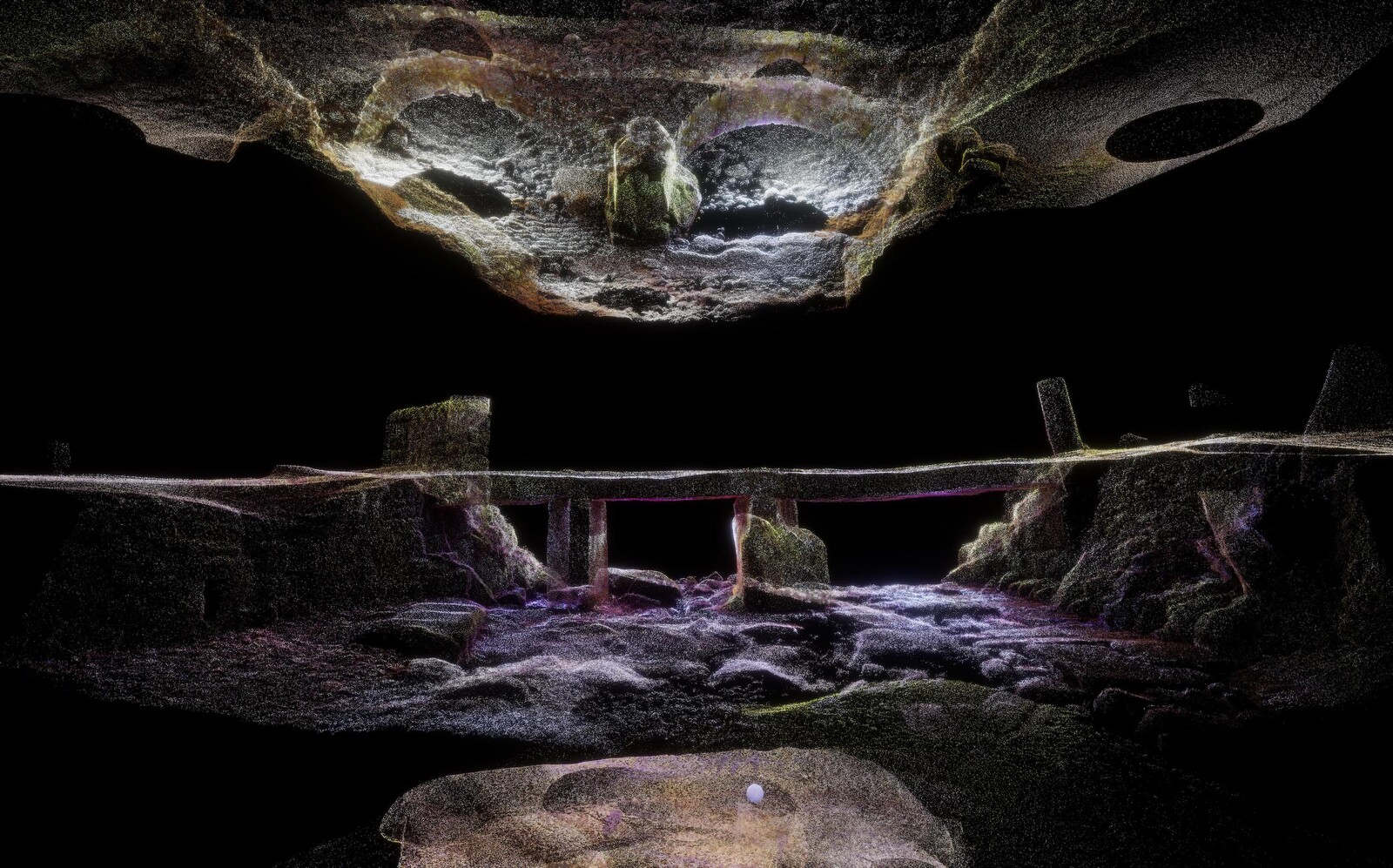

Visitors to the Van Gogh “Experience” can pay extra for a ten-minute VR video (VR being, on the scale of the “immersive,” an eleven, with big 360-projection being a nearby ten, loud symphonic music a steady eight; your standard single-screen projection a mere five, and reading a book, by this metric, being a one). We’re given a ghostly tour of Arles, propelled forward as we drift through cafes and fields; all you can do is look around you from your chair, a disconnect which left me with motion sickness. The VR Arles bears no small resemblance to Mark Leckey’s VR work The Bridge (2023), being shown as part of the group show “Tremulations” at Swedenborg House. Here, we are moved along by an unseen force under a haunted motorway overpass, eventually sinking through the ground to see earlier, primordial iterations of the structure, as a stone bridge and ultimately an ancient stone passage. In both cases, it’s as if we’re strapped into a ride, maybe coasting along in something like the original “Pirates of the Caribbean.” The proximity to Disneyland is no accident, with the immersive’s desire to overwhelm the audience into investing in its proffering of the fantasy made real: to be in an artwork, to be in a dream. But whose dream? The VR joyride is the apex of the immersive, and its relentless promises of engagement and interactivity: a seasick passenger on a ghost ship, a passive witness pulled inexorably forward through its world—all you can do is try to look away.

See Victoria Cain and Karen Rader, “From Natural History to Science: Display and the transformation of American museums of nature and science,” Museum and Society Journal, Vol 6, No. 2 (2008): 152–71.