In one of my earliest memories, I’m swimming alone in fins and goggles across a bay in the Adriatic Sea. Everything is illuminated: emerald seaweeds, milky pink actinias, chromed silver fish, and my legs shining like a mermaid’s tail. Which is magic: on terra firma, ichthyosis (from ichthys, Ancient Greek for fish) makes my skin scaly, so that, as etymology suggests and dermatology recommends, salt water is my natural element. Bodies and cells know best. As Joan Jonas likes to point out: “somewhere in our unconscious we remember that we come from the sea. It’s not a memory; it’s a feeling; it’s in our DNA. I think that’s where all these stories come from and our desire to go back to the sea, our desire to swim under water, which I love to do.”1

In her multimedia installation Moving Off the Land II (2019), exhibited at Ocean Space in Venice and curated by Stefanie Hessler, we see Jonas swimming in a dress (red and polka-dotted, or dark and transparent) with a cloud of silver hair snaking gently around her head. In these videos, shot in Jamaica by filmmaker Cynthia Beatt, she looks like a luminous apparition, an aquatic creature whose colored patterning interacts with water and light like that of the fish, manta, jellyfish, seals, lobsters, turtles, and corals that share the stage with her.

The exhibition occupies the cavernous architecture of the former Church of San Lorenzo, the interior walls of which are covered in restoration scaffolding, in two different ways. The front room is left empty, except for a large painting of a sperm whale installed above the main altar. A sound piece immerses viewers in the loud, clicking vocalizations emitted by the whales to communicate with each other, reverberating across the vast nave: a language that humans are unable to understand, despite being endowed with the same hearing apparatus (the semicircular canals of the inner ear) as all jawed vertebrates. It’s in this space that Jonas twice performed Moving Off the Land during the chilly (and very wet) opening week of this year’s Venice Biennale.

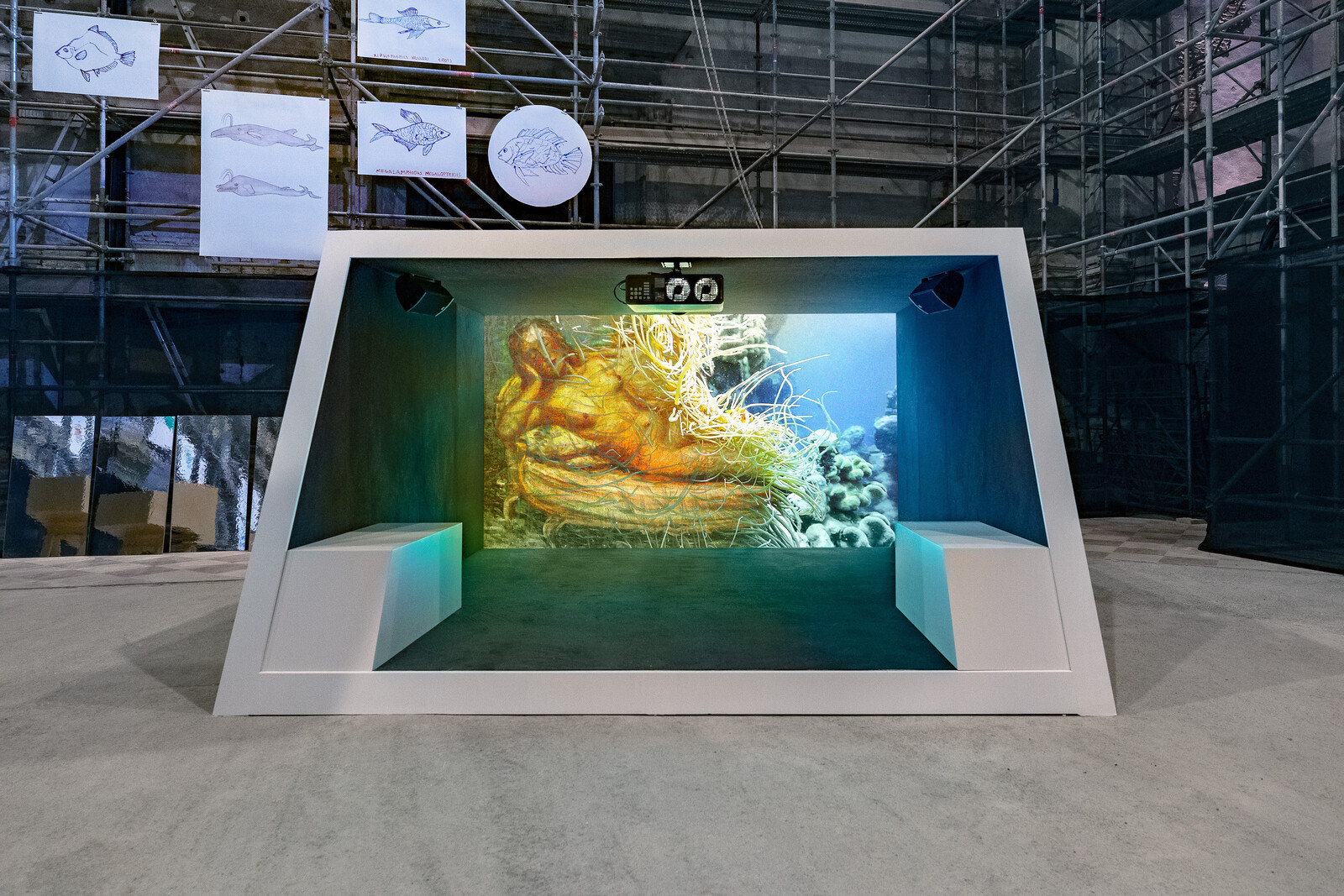

By contrast, the second room is full. Above eye level are suspended prints and ink drawings of different fish species traced in the artist’s signature calligraphic style—a continuation of her fish drawings developed in preparation for the installation and performance series Reanimation (2010/12/13), which she described as “a descent into liquid, an absorption in activity and the actualities of the archeology of the ocean.”2 Thin sheets of acrylic mirror and Murano ripple glass are positioned along the walls, to reflect and multiply the five wooden structures positioned at the center, building upon her “My New Theater” series (1997–ongoing). Two are small “looking boxes” (or miniaturized cinemas) mounted on wooden legs, while three are large walk-in boxes that allow viewers to sit next to the screens and add their shadows to the glowing video projections.

As is characteristic of Jonas’s works, visions are layered, with still and moving images of oceanic creatures projected over still and moving bodies, including the artist’s own. Like tides and waves, they move back and forth over time. Jonas shot portions of footage in aquariums in Italy, Norway, Japan, the US, and Jamaica (commissioned by TBA21–Academy), while others are the result of a recent collaboration with marine biologist and coral reef and photosynthesis expert David Gruber, who shared with Jonas his high-res, underwater footage of biofluorescence. There are several excerpts from previous performances in the “Moving Off the Land” series (2016–ongoing) in which Jonas draws, paints, makes music, plays, and dances with the digital doubles of other species, as if to wear their colors and fuse with them. She evokes the ancient figure of the mermaid and narrates the tale of a clever caged octopus who sneaks out of his tank every night to hunt for fish in an adjoining tank and comes back undisturbed before gates open to the public. After all, humans have projected their comportment onto other species since the dawn of time.

And yet, elegy and extinction loom on the horizon. “Fish. Bees. Birds. Creatures that are disappearing. The ghosts linger as memories,”3 Jonas wrote about They Come to Us without a Word, her project for the US Pavilion at the 2015 Venice Biennale, focused on the fragility of all living forms. Here, her obsessive fascination with integuments and the optical textures of other living bodies is deeply moving, precisely because it asks us to move beneath skin-deep aesthetics to find other paradigms of connection with the beauty of “natural” life. She reminds me of another avid swimmer, the late philosopher Agnes Heller, who wrote: “That which is beautiful can be the shapes and the forms, the things of nature, artifacts, men and women, the soul, deeds, characters, states, states of mind, friendship, love, propositions, gestures, behaviour, expression, works of art, and so on.”4 Underwater, as Jonas’s liquid mirages prove, it feels crystal clear.

Agnieszka Gratza, “We Come from the Sea,” www.tba21.org/journals/article/We-Come-from-the-Sea.

Joan Simon, “Migration, Translation, Reanimation,” in Joan Jonas, Joan Simon, In the Shadow of a Shadow: The Work of Joan Jonas (Gregory R. Miller and Co., Hatje Cantz, HangarBicocca, and Malmö Konsthall, 2015), 116.

Ibid, 119.

Agnes Heller, “What Went Wrong with the Concept of the Beautiful,” The Concept of the Beautiful (Maryland: Lexington Books, 2012), xliii.