March 13–July 20, 2024

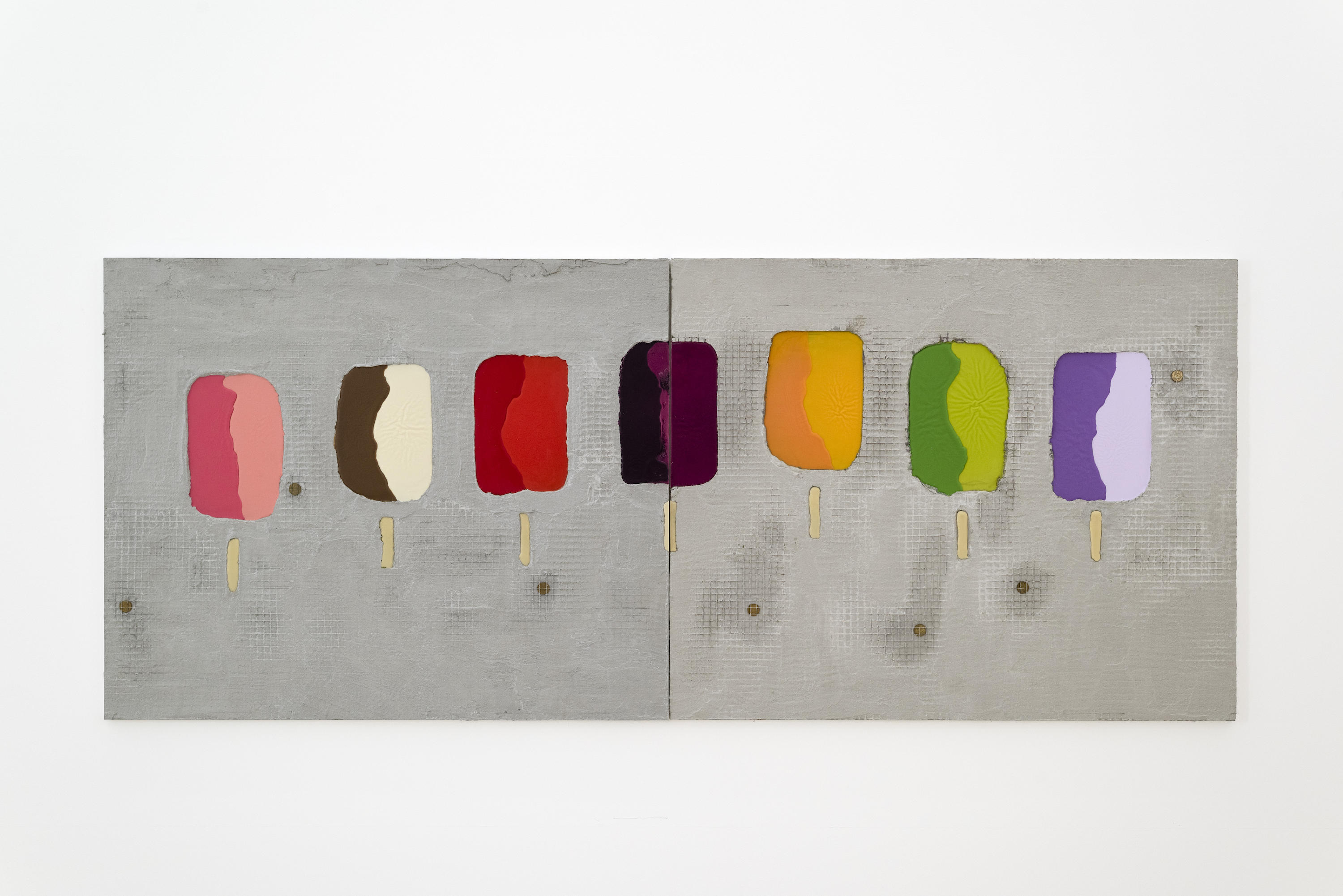

Marwan Rechmaoui’s latest body of work includes paintings of popsicles and bags of pink cotton candy. There are poppies, fluffy clouds, a pretty sun, and a full moon. The perfectly green crowns of seven parasol pine trees fill one robust frame while the bushy derrieres of three sheep fill another. Among the objects scattered throughout “Chasing the Sun,” on view in the Sfeir-Semler Gallery’s newish project space located in Downtown Beirut near the mouth of the port, are streamers, a kite, marbles, the outlines of a hopscotch game, and boards for checkers and tic-tac-toe. Knowing the artist’s previous work, one could be forgiven for thinking he’d lost the plot here, or at least wandered off toward divertissement. And yet the toys and games of the current show clarify the importance of play and playfulness in Rechmaoui’s larger project. Taken in their imaginative spirit, they question whether the very concept of play—as expressed in art or set against ideas about work, leisure, care for others, and the waging of war—should ever be considered a distraction, a digression, or a detour from the serious stuff.

Born in Beirut in 1964, Rechmaoui lived in Abu Dhabi before moving to Boston, where he became a painter at art school and a furniture maker on the side. After a spell in New York, he returned to Beirut at around the time that Lebanon’s civil war was coming to an unsteady end. For three decades since, Rechmaoui has been mapping his hometown as both a means of artmaking and a mode of knowing his place in the world. His untitled paintings from the 1990s represent Beirut through the materials of its postwar reconstruction. Flashes of orange plastic and the stainless-steel grid lines of standardized wire mesh peek through layers of asphalt and concrete. For Beirut Caoutchouc (2004–8), Rechmaoui carved out the shape of the city in thick black rubber. Sixty interlocking pieces, each grooved with streets and alleyways, fit together on the floor like a large industrial slip mat, inviting people to walk all over it or get down on their hands and knees for a closer look. Blazon (2015), by contrast, is an installation of some 400 flags hanging above viewers’ heads. Each flag is embroidered with a coat of arms, which Rechmaoui’s designed to correspond with specific neighborhoods—as if Beirut’s complex urban fabric might one day play out like a more finely grained, densely sectarian version of the crusades.

In Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture, first published in 1938, the Dutch cultural theorist Johan Huizinga proposes man the player (Homo Ludens) in place of man the maker (Homo Faber) and man of reason or wisdom (Homo Sapiens). Huizinga argues, memorably, that play is older than culture, that it is essential, irreducible, and distinct from other thought-forms. Most importantly, in Homo Ludens, play is free. “Play cannot be denied,” Huizinga writes. “You can deny, if you like, nearly all abstractions: justice, beauty, truth, goodness, mind, God. You can deny seriousness, but not play.”1 Play has the potential to create order. It is spontaneously invented, then passes immediately through ritual to the status of tradition. It is also, as many have ventured, including Roland Barthes in his short text on French toys, a rehearsal for the unlovely aggressions of adult life and a preparation for war.2

None of the artworks in “Chasing the Sun” are as innocent or whimsical as they appear. Paintings such as Sun, Moon(s), Strawberry, and Cotton Candy (all works in the show are 2024) are made of pigments and molten beeswax plunged into layers of grout cased in aluminum. The objects include a silk paper kite (Mozi Kite) and a black inner tube (Chambre à Air), but also a Molotov cocktail, a slingshot, a handmade rifle, and sandboxes for stacking rocks and throwing knives. Moreover, the games come from the pages of an old sketchbook, recently salvaged from the artist’s effects, in which Rechmaoui recorded the things that he and his friends got up to when they struck out from their neighborhood as kids.

These artworks mark out the edges of an earlier city, a previous Beirut. If play is older than culture, then violence is nothing if not primordial. Can the playfulness of Rechmaoui’s work inspire anything in us, as viewers, to throw off that progression toward war, from games and contests to armed conflict and strategic destruction? Huizinga summons Plato to remind us that “life must be lived as play.”3 Maybe Rechmaoui’s recent work offers an alternative. Play need not be dutiful, nor a retreat into childhood. The ingenuity of each (aesthetic) object proposes its own world. Each world suggests a set of rules but remains crucially open ended. Entering into those worlds, one after another, isn’t an experience of arrested development but rather an exercise in finding paths forward. Rechmaoui’s diversions, by turns joyous and sinister, thrilling and foreboding, could be our only ways out of a dead end.

Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture (Kettering, OH: Angelico Press, 2016), 3

See Roland Barthes, “Toys,” in Mythologies, trans. Annette Lavers (New York: Hill & Wang, 1972), 53-4.

Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture (Kettering, OH: Angelico Press, 2016), 212.