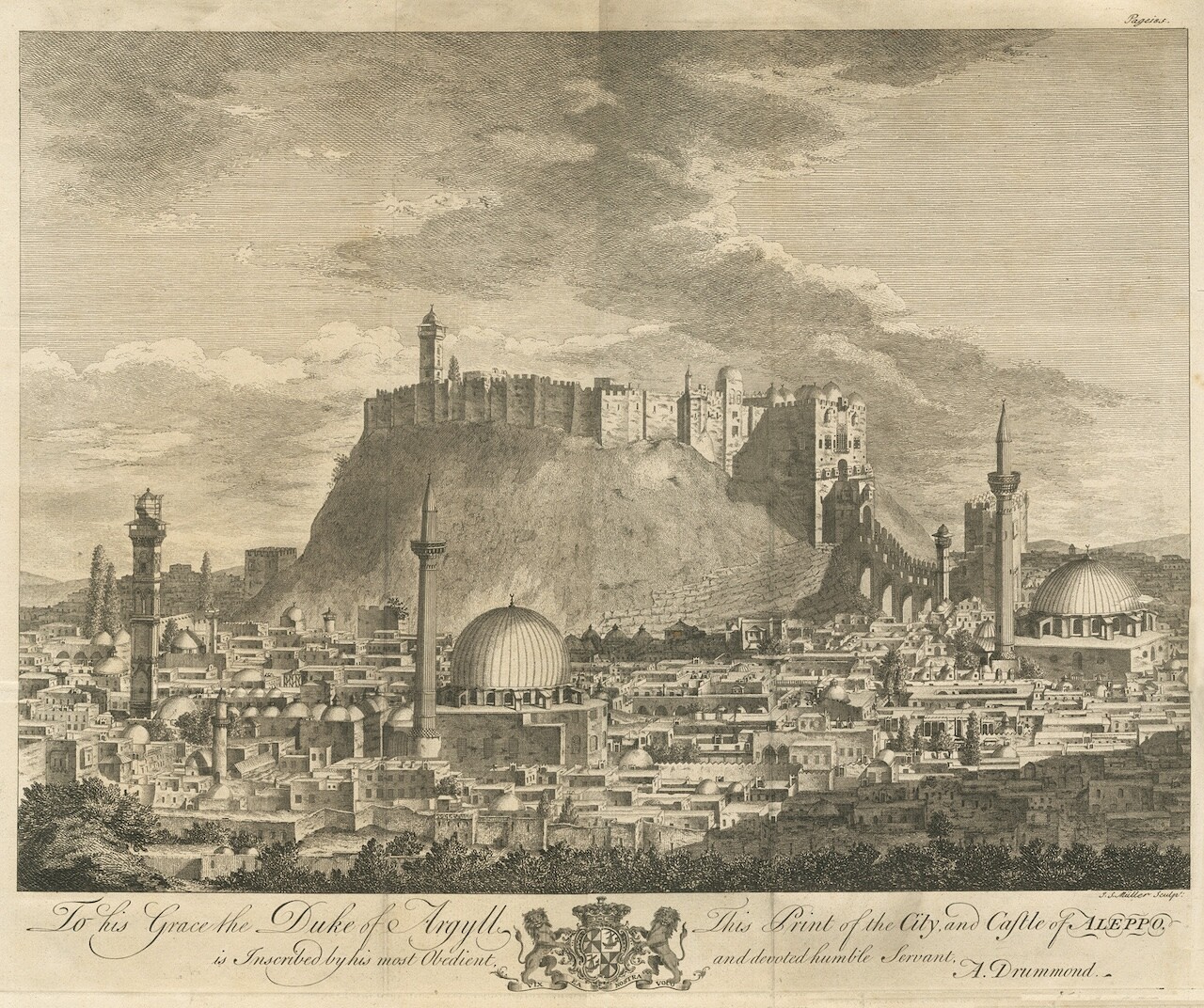

Alexander Drummond, City and Castle of Aleppo, 1754. License: Public domain.

Discussing a guaranteed roadmap for Syria and its neighbors seems nearly impossible today. The reality is that the people of this region, and most of the areas that were under Ottoman rule, lack a representative model. The Ottoman Empire fell before completing its annihilation and achieving regional ethno-religious uniformity, unlike Europe, which underwent wars spanning centuries.

The unachieved “goals” during those dark decades of human history in Ottoman territories created significant obstacles to modernization at all levels in these newly formed countries. It was as if these countries committed genocides in installments because they failed to execute them all at once.

These countries emerged shortly after the end of Europe’s bloody great wars. They were born in the midst of Europe’s bright realization that continuous wars on the continent were exhausting to the point that it was safer to hand the victims the banners of victory. The great European wars ended in the mid-twentieth century with a decisive elevation of the victim’s status. Since then, regret and fear of adventure have driven politics and shaped the public mood. Europe, saturated with its people’s blood at that moment, could not endure any more bloodshed. This saturation acted as a safeguard for future generations and an obstacle to developing its systems and constitutions in the direction of ethno-religious uniformity.

Unfortunately, the countries born from the collapse of the Ottoman Empire embraced modernization and the values of modernity and the nation-state just as signs of a crisis in European liberalism were becoming evident. This led to a rise in the voices of populist forces demanding the return of Europe to Europeans. The history of the states that emerged after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire seems to have been sacrificed twice: first, for not achieving ethno-religious uniformity when genocides were common, and second, for embracing the hope of creating diverse and tolerant societies just as signs of hatred began to appear in those countries that promoted tolerance and human value.

Syria, among these newly born countries, may be the most diverse and complex. It is undoubtedly the most experimental in plans, ideas, and means for building an inclusive state. However, the Syrians’ efforts have not prevented their country from being affected by global and local dynamics beyond their control. The concept of a democratic state there was elitist. Since the early twentieth century, the elites assumed that ascending to citizenship required qualities that ordinary people lacked. One is born as a member of a sect, family, or tribe and must advance in education and culture to become a citizen. Citizenship was never a given for Syrians; it had to be earned through knowledge and learning.

These elite pathways were not without arrogance toward the common people. Political parties aimed to educate society to become mature and ready for modernity’s demands, much like their European counterparts. European modernity committed massacres in its countries that previous empires did not. From the Nazi Holocaust to Stalinist genocides, modernists killed in the name of the nation-state and a homogeneous society those who were not eliminated in the church wars of the Middle Ages.

The Middle East was born from these intertwined and complex realities. The secular elites who controlled its fates failed to replace faith with citizenship. The obstacles were primarily social, sectarian, and ethnic, with economic challenges also playing a significant role. It was clear that for the nation-state to stabilize itself, sociopolitical divisions had to be transformed from sectarian to modern divisions. Social classes determined by economic level are essential for stability.

This condition was not met in the countries that emerged from the Ottoman Empire due to two main reasons:

- The various communities within these emerging countries were homogeneous within their regions and along their borders, but this homogeneity was primarily sectarian and ethnic.

- This prevented the formation of a citizen class and modern urban centers.

Cities remained as a collection of heterogeneous neighborhoods, meeting in diverse markets and separating into particular neighborhoods; they failed to transform themselves into modern cities where individuals are united under the same law.

Because armies were the only institutions that were formed along secular lines, they became the longest-lasting authorities. It’s no secret that military states in the Middle East, including Syria, exhausted their advantages and capital decades ago. Bashar al-Assad’s regime survived on the absence of alternatives. These regimes, which no longer had answers to the dilemmas facing them, fed on their failure to transition those they ruled from the status of kin to citizens.

Today, Syria suffers from a prolonged neglect of its traditional society and deadly corruption among its ruling elites. These elites lack answers to even the simplest and most obvious problems, while traditional societies are managed through oppression under the pretext of their being unsuitable for modern times.

In summary: Secular elites (who have turned into sects also), influenced by the policies of traditional sects, no longer have much to offer or suggest for Syria’s future. The forces that have taken over and those that are expected to join them in establishing new authorities are predominantly traditional forces. They have much to fear from other forces they must coexist with but also many commonalities that could achieve real coexistence among Syria’s components.

The new constitution and laws that will likely emerge will consider these formations first, highlighting commonalities to keep Syria intact as a state with multiple origins and orientations. The opposition forces’ easy victory over Bashar al-Assad’s regime was not solely due to the great sacrifices of the Syrian people. It also stemmed from the experience that the armed opposition forces gained in northeastern Syria over recent years. During this time, they established governmental, administrative, and judicial authorities in the region and successfully achieved social and economic stability despite their meager resources.

The most crucial reason for the tendency of Syrians to have consideration for one another is the enormous human, social, and economic cost incurred over decades, especially post-2011. This cost deters Syrians from engaging in further conflicts. The new policy phase in Syria might be best titled “modesty,” reflecting the new leaders’ statements: “The Syrian people are exhausted and cannot wage more wars. There is no place for revenge in the new Syria.”

However, peace is not guaranteed. The challenges are enormous, particularly the technological and economic changes imposed by globalization. While these groups may succeed in establishing a subsistence economy, achieving regional prosperity and flourishing remains uncertain. Modern technologies encourage individualism, not group identities and cohesion, leading to unrest if attempts are made to freeze the country within its constituent frameworks.

Reconciling group traditions with globalization’s demands will require significant effort from all Syrians. Syria is currently at zero, needing strenuous efforts and innovative solutions beyond conventional answers.

The main conclusion about Syria’s future concerns the inability of secular elites to keep pace with developments. For the first time in modern history, secularists lack answers to the most pressing questions, relying on previously adopted answers that led to rounds of violence, leaving little of Syria’s modernity intact.