These twinned exhibitions span Issam Kourbaj’s responses to the civil war that has carried on in his home country since the uprising against Bashar al-Assad in March 2011, expanding to consider related conflicts in the Middle East and the broader plight of refugees. Trained in Damascus, Leningrad, and London, Kourbaj moved to Cambridge in 1990 and has over the past thirteen years harnessed metaphor’s literal Greek meaning—“to carry across”—to the archival impulse to catalogue and connect.

Inspired by prisoners who smuggled their names out of a Syrian jail to let their families know they were alive, Urgent Archives, written in blood (2019) consists of disbound books and papers—perhaps the dead stock of an antiquarian bookshop or college library—loosely gridded on the floor, some “hovering” on blocks. In black, blue, and blood-red ink, Kourbaj has marked them with erratic lines and handwritten Arabic script. One book is stamped with the (English) words LEAVE TO REMAIN, signifying a refugee’s permission to stay in the UK—the granting of which is unguaranteed, racially biased, and often long-awaited in one of the country’s prisonlike detention centers.

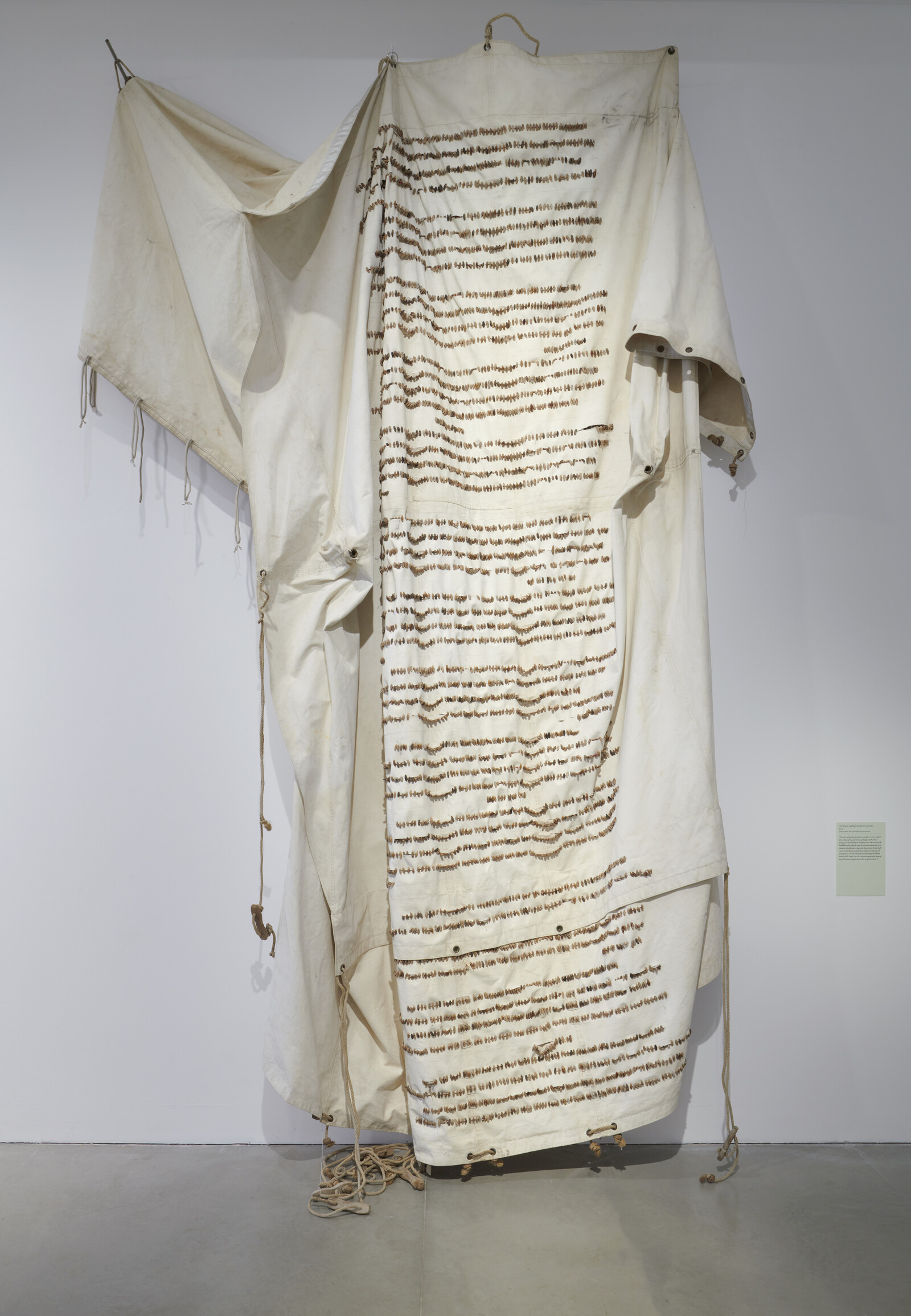

Every day since the uprising, Kourbaj has sewn a date stone into a tent fabric to create Our exile grows a day longer and a day closer is our return (2024), craggily pinned to the wall and resembling a ritual megalith. A vitrine presents volcanic rocks from his hometown of Suweida, reassuring in their endurance and as topographical relics conflating “here and elsewhere”.1 Showing on a monitor is a video document of the contrastingly ephemeral performance Imploded, Burnt, Turned to Ash (2021), in which Kourbaj memorialized the tenth anniversary of the uprising by scrawling a poem on a large sheet of paper, which he then tore up and burned. Packets of Syrian wheat seeds, samples of which have sprouted from a plastic tray, also participate in the measuring of time in objects, plants, marks, gestures, and geographies. The impression is that keeping track might fill the void.2

Unlike photographs or video clips of war that always remain other to the peacetime viewer, metaphors depend on our own cognitive, translatory participation—they get inside us. This is fundamental to how Kourbaj’s work reaches beyond itself, and why All But Milk (2023–24) is so excruciating. Several hundred milk bottles, some with teats attached, some broken, variably containing sand, rocks, blood, bits of plastic—it’s hard to really see them, lined on high shelves, as if to protect them from the visitor’s gaze. The wall text reveals the work’s referent: the children of Gaza. If, in Kourbaj’s alchemical metaphors, green-sprouting wheat is hopeful, here milk represents the waste of life. In the continuing absence of a ceasefire, the artist presents a site of mourning and bearing witness.

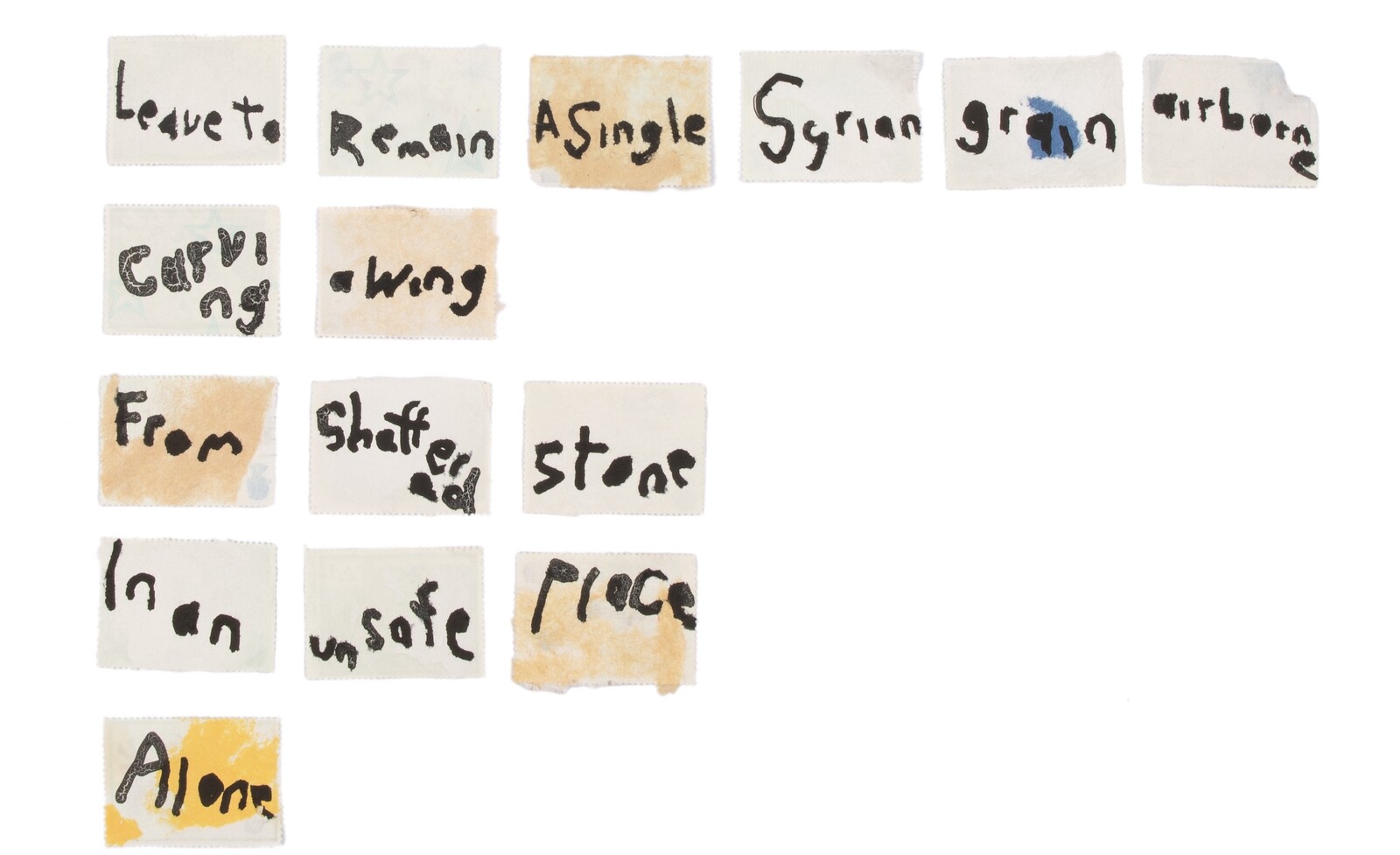

Kourbaj’s found poem Leave to Remain: A single Syrian grain airborne (2020) threads through his exhibition at Cambridge University’s Heong Gallery, which engages with the UK’s increasingly hard border. The poem’s call-and-response—in which the oxymoronic term “leave to remain” meets rejoinders such as “lifeless” or “Aleppo devastated”—is embossed into a lead lifejacket (The Sky is Sinking, 2023) or handwritten, in Arabic and English, on the backs of postage stamps. An affecting representation of the notorious Bibby Stockholm—a disease-ridden, deliberately dehumanizing migrant detainment barge moored off the country’s southern coast—Keep Them at Bay (2023) is composed of sardine tins on a wooden base, the corner of which juts off its shelf to draw attention to the engraved words of its title.

In an interview published in the exhibition catalogue, Kourbaj declares his intention to “make work that can be read universally, not only about Syria […] We are all in the same fragile boat in many ways.”3 The idea illuminates a rudimentary sculpture of what might be just such a vessel, perhaps the next addition to the flotilla of miniature metal boats filled with spent matches that constitute Kourbaj’s ongoing Dark Water, Burning World (2016–). Rather than suppress differences between people and places, Kourbaj posits universality in the space in-between, which is traversed by small boats, metaphors, and other carriers of meaning.

Issam Kourbaj’s concurrent shows “Urgent Archive” at Kettle’s Yard and “You are not you and home is not home” at The Heong Gallery are on view through May 26.

Alexander Nagel discusses topographical relics in relation to the artist Robert Smithson’s “note-sites,” comparing ways in which they embody such displacement, in Medieval Modern: Art Out of Time (London: Thames & Hudson, 2012), 122.

Hisham Matar writes: “Perhaps this is why, in countless cultures, people in mourning rock or sway from side to side—not only to recall infancy and the mother’s heartbeat, but to keep time. Only time can hope to fill the void.” See Hisham Matar, The Return: Fathers, Sons and the Land In Between (London: Viking, 2016), 166.

Issam Kourbaj, “View from the studio: A conversation between Issam Kourbaj and Guy Haywood,” in Issam Kourbaj, ed. Guy Haywood (Cambridge: Kettle’s Yard, 2024), 70.