The central character in Diane Severin Nguyen’s video IF REVOLUTION IS A SICKNESS (2021), which comprises her institutional debut at Sculpture Center alongside four color photographs, is a Vietnamese girl named Weroníka who literally washes up on the shores of Poland. In the opening sequence, a male voice addresses her in Polish over shots of soggy grey landscapes. His obscure phrases are charged with radical sentiment as low piano music escalates the tension: “This is the condition for understanding the collective as a process. Isolation will destroy you.” When Weroníka appears onscreen in a yellow shirt with red sleeves, she is accompanied by sound effects: a mechanical breathing noise ends in a metallic click as she opens her eyes; percussive noises punctuate her repeated, dance-like gestures. Later, she nods her head to the thumping bass of a pop song playing on her headphones while the man’s voice declares that knowing the “truth” of a spectacle comes at the price of not participating in it.

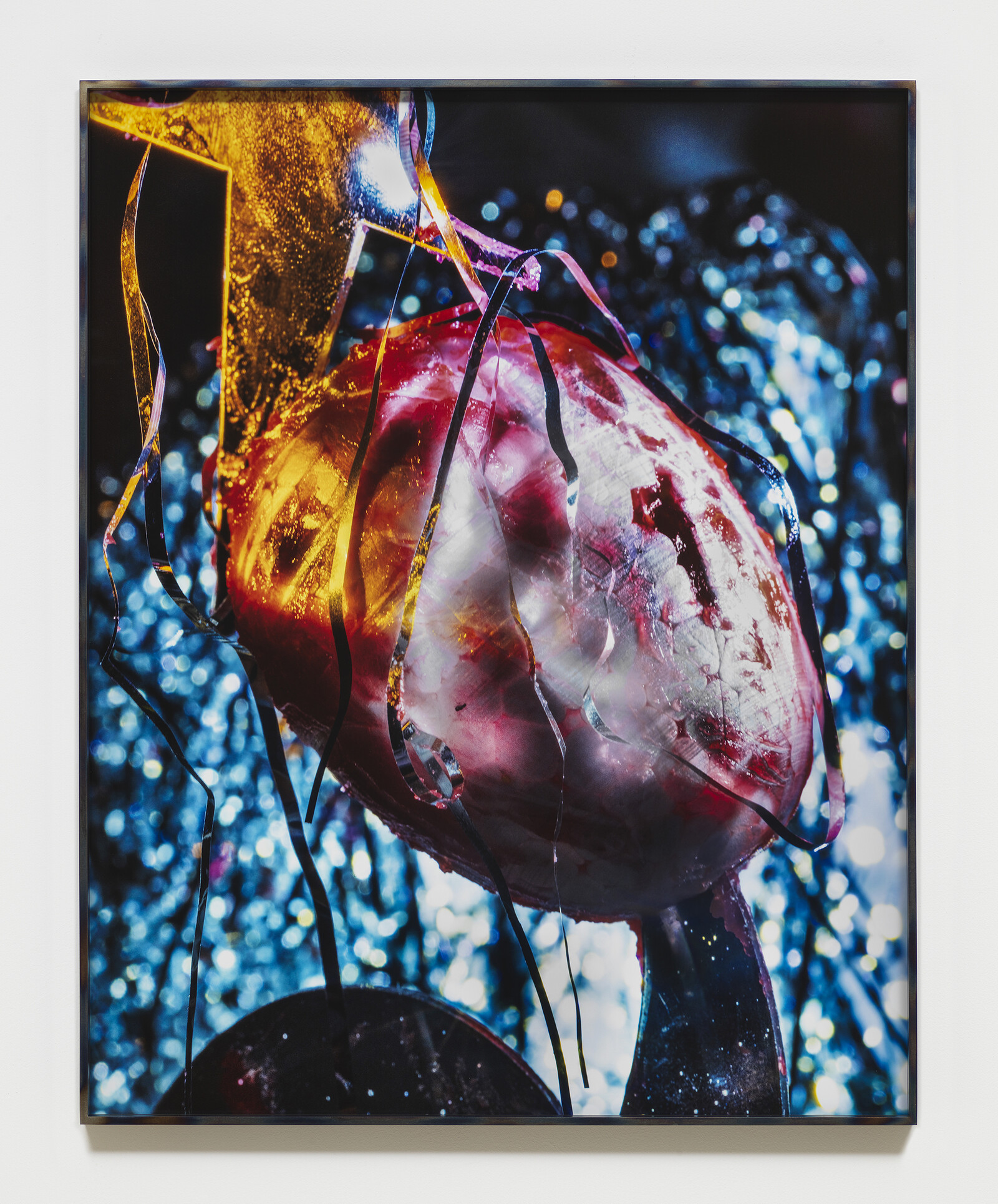

Nguyen’s sound effects complicate the viewer’s relationship to Weroníka, as does the staging of the video. Flanked by two PA speakers and pleated yellow fabric, the screen on which the video is shown is mounted on a stage in the Sculpture Center’s main hall. Red carpet covers the floor, lending the presentation the feel of both a middle-school pageant and an old-school political campaign rally. This red-and-yellow color scheme, which reflects the color palette Nguyen uses in the video, is one of many details in the work that feel loaded with the ideological weight of the Cold War but also possess a straightforward aesthetic charm. The cryptic voiceover, which weaves together potent lines of conflicting twentieth-century thought (such as Mao Zedong, Hannah Arendt, and Ulrike Meinhof) lends further gravity to the images. Nguyen’s work insists that certain symbols have many meanings at once—some grandiose and clichéd, others irreverent and chic—while others carry a more visceral truth. In what looks like a graveyard, a young man in a red bandana holds up an antique hammer resembling that which accompanies the sickle in the Soviet flag. A few seconds later, someone digs a shard of glass into a ripe strawberry. By welcoming such potent and divergent references into the work, the artist destabilizes the very tools she uses to depict her subject.

Snippets of what may be Weroníka’s internal monologue are spoken in Vietnamese with English subtitles. Now a lonely teenager, we see her sitting contemplatively on a bridge overlooking a large river, and practicing dance moves in emptied-out factories strewn with rubble. A close-up of a rusty spiked chain echoes the chrome-plated necklace around Weroníka’s neck, from which hangs the letters “D-A-R-K.” She wonders aloud: “Where is there a beautiful surface without its terrible depth? Do they really think I’m cute or just different?” Her status as an outsider in Poland—whose current right-wing government is decidedly anti-immigrant—comes into focus. In this context, the word on her necklace changes from a goth accessory to a racialized label, and the slippage between the personal and political occurs within this shiny piece of jewelry. Weroníka then pivots from self-doubt to a vision of agency: “If I don’t become an artist then I will just remain a victim. I must appear to myself as I wish to appear to others.”

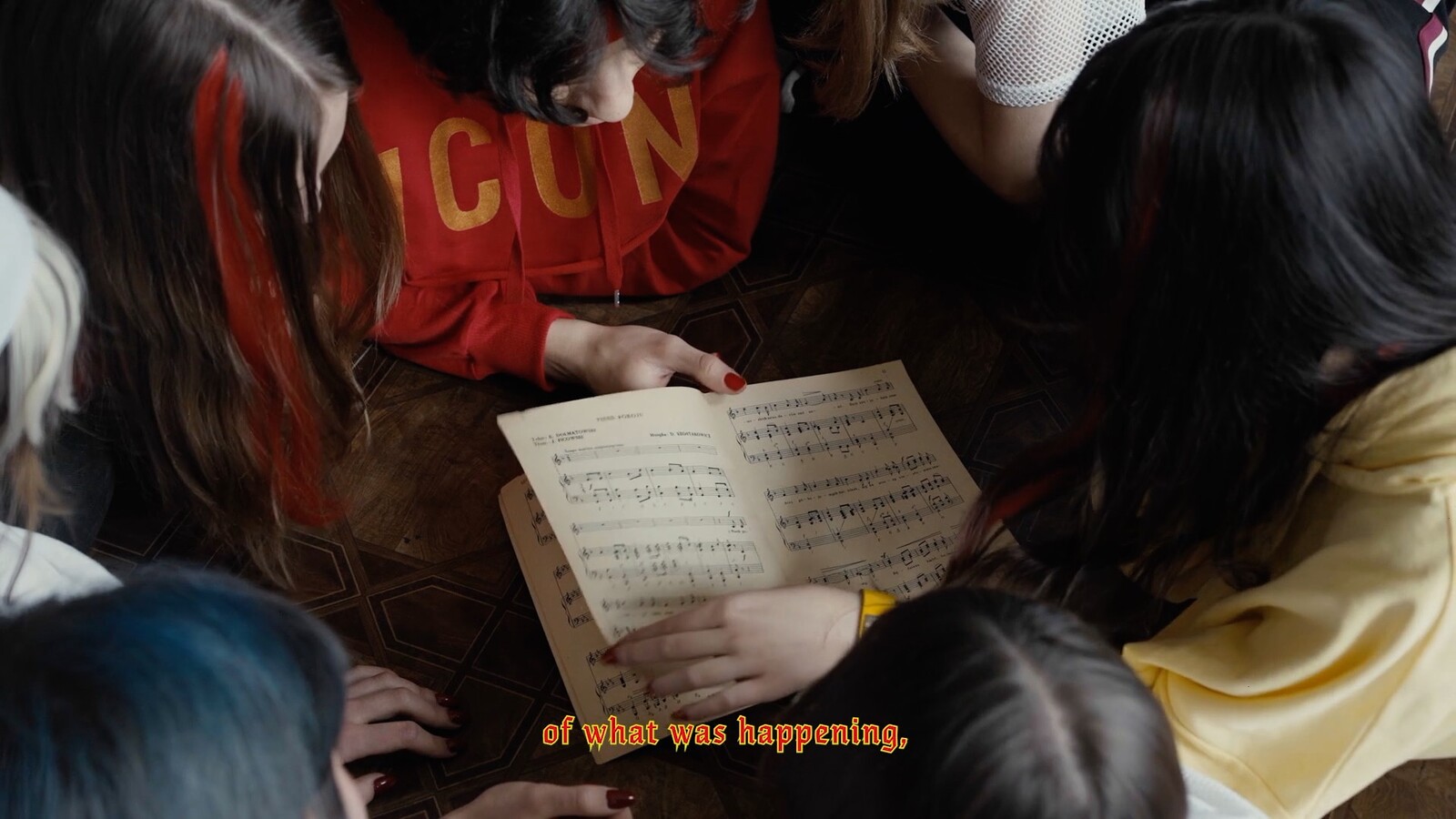

In the video’s final segment, which amplifies the disjointed symbolism and humor of the work, Nguyen substitutes revolutionary rhetoric for song lyrics in a K-pop inspired music video. The format will be familiar to anyone with an internet connection—a group of Polish teens in matching outfits performing syncopated dance moves over a catchy song with lots of autotune—but they dance in front of dreary war monuments and Stalinist buildings instead of glamorous sets. The lyrics mash up outdated revolutionary clichés with inane cultural ones of prosperity: “The world keeps spinning and we keep on winning. Our blood is pumping as one.” This juxtaposition results in a state of mutual alienation in which neither rhetoric has much traction, and the self-consciousness of the performers takes center stage. Weroníka’s lips move slightly out of sync with the lead vocals, adding to the artifice of the performance. This little glitch raises the question of to what extent Nguyen is acting as a ventriloquist in this work and blending her own experience of the Vietnamese diaspora with these teens in post-communist Poland.

By ending the work with a music video, Nguyen indulges in the joyful absurdity of globalized subcultures without mocking the underlying desire of adolescents to feel a sense of belonging and establish their identities amid and against their particular histories. The glossy, upbeat production sweetens the delivery of a devastating line: “I swam from the ocean searching for a new nation / I lost my family that day.” Later, seven teenagers sing together in an abandoned building: “Does your loneliness have a name? Was the freedom worth the pain?” In this moment we glimpse the pathos that accompanies this generation’s peculiar inheritance. Whether this freedom refers to capitalism, the new life that awaits immigrants, or the agency of individual subjects and their social media avatars, is less important than the fact that it remains bound up in loneliness and pain.