Arseny Zhilyaev traveled to Manifesta, the European Nomadic Biennial. Back in the day, it was one of the Old World’s most experimental art venues. “The Planetary Garden,” its twelfth edition, opened in June in Palermo.

The attempt by Italy’s newly minted right-wing populist government to reject a boatload of 629 refugees from Africa this June triggered a story that became Manifesta 12’s epigraph. A few days before the biennial’s official press conference, Palermo’s mayor, Leoluca Orlando, stormily announced he was ready to take on the federal government in Rome. He argued Italian authorities were violating international conventions and humanitarian principles, thus leaving him with no choice but to let the ship carrying the refugees dock at the port of Palermo, a city that has long incarnated hospitality and cultural intercourse. Orlando spoke on nearly the same topic at the opening press conference. Needless to say, given the previous two biennials—Manifesta 10’s “window on Europe,” held amid St. Petersburg’s imperial splendor, and Manifesta 11’s discussions of how artists could make money, held in one of the world’s most expensive cities, Zurich—the rhetorical tone adopted by Manifesta 12 seems timelier and more in keeping with the biennial’s original brief to exhibit new, politically engaged experimental art.

Manifesta 12’s curators—or “creative mediators,” as they were called—are OMA partner and Italian architect Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli, Kunsthaus Zurich curator Mirjam Varadinis, Dutch filmmaker and journalist Bregtje van der Haak, and New York-based Spanish architect and scholar Andrés Jaque. They hit upon a happy metaphor for launching the biennial: “the planetary garden,” a term coined in 1997 by French botanist Gilles Clément. In his original conception, Clément identified humanity as the gardener, collectively in charge of the garden’s welfare, a blunder the curators eliminated by stressing the need to criticize anthropocentrism.

The exhibition venues and original themes were selected by Rem Koolhaas’s OMA, which also compiled the “Palermo Atlas,” a comprehensive urban study of the city, for the event. So far, so good. Most of the venues are fantastically beautiful palazzos in varying states of dilapidation. Access to them—which is blocked during non-biennial time—is a gift of the exhibition’s organizers and city administration. Another godsend is Palermo’s botanical garden, which hosts several projects and can in itself be considered a manifestation of the biennial’s title. Given such a setting, contemporary art can at best aspire to witty commentary. Seemingly, no attempts to raise this benchmark have been made. What is worse, in terms of display methods, the show strikes viewers as not only merely conservative, but also frankly tedious and unpersuasive.

A careful study of the 48 projects shows how the organizers tried to cover almost all the issues of the day, from AI and total surveillance to the corruption of Sicilian authorities. The former may be found in Trevor Paglen’s It Began as a Military Experiment (2017), which comprises a series of photographic portraits which shed light on military projects dedicated to developing facial recognition technology, or in Richard Vijgen’s data visualization Connected by Air (2018), which visualizes Palermo’s sky filled with wireless signals, satellites, and other participants of cosmic traffic. The latter issue—civic corruption—is addressed in Belgian group Rotor’s Da quassù è tutta un’altra cosa [From up here, everything looks different] (2018), an environmental intervention in a remote housing complex on the north of Palermo, which stands as an abandoned monument to clandestine real estate deals. Another piece related to local politics is Laura Poitras’s multilayered installation Signal Flow (2018), dedicated to decades of Sicilian citizen resistance to US military presence on the island.

The desire to work with new names, or at least avoid jaded stars, is to the curators’ credit. Its flip side is the large number of run-of-the-mill projects and participating artists’ deployment the planetary garden metaphor literally and didactically. Needless to say, the word “garden,” alongside varieties of plants and fruits, figure an indecent number of times in the titles of works.

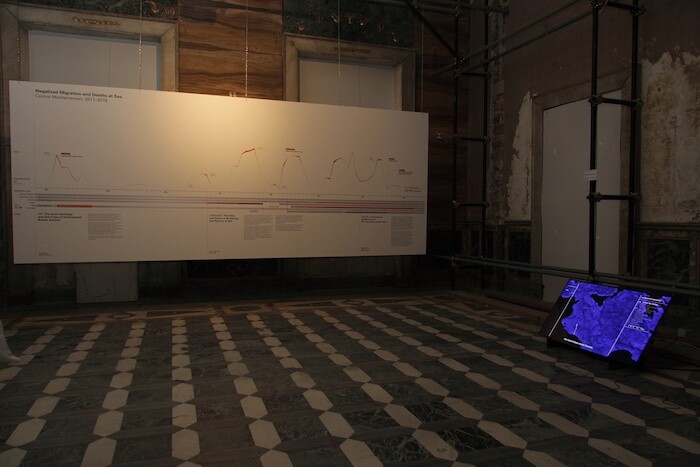

But of course, there are exceptions. Forensic Oceanography’s video installation Liquid Violence (2018) brings together different consequences of EU and Italian policy in relation to the migrant crisis. Using the language of a detached report, proved by numbers and concrete decisions, Forensic Oceanography depict a realistic image of current biopolitics, in which thousands of lives are doomed to death. John Gerrard examines another trace of immigrantion policy. His Untitled (near Parndorf, Austria) (2018) emerged from the artist’s journey to a nondescript section of motorway in the south of Vienna on Saturday August 29, 2015. Using news photos, Gerrard identified the place where, two days previously, an abandoned truck was found. The vehicle contained the bodies of 71 migrants, all of whom had suffocated. Using a computer game simulation engine, the artist reconstructed hyper-realistic video that portrays, in a very calm manner, the highway on the same date.

Providing a rationale for the biennial by employing “architectural” methods of curating has elsewhere produced a slightly mechanical effect. The show comes across as a condensed, relatively superficial compilation of the zeitgeist made by people who lack the bravery to act in an unconventional way or think beyond the exhibitionary logic and the thematic standards of biennials from several years ago. This is partly a result of broader problems intrinsic to the medium of a biennial, and to historical circumstances—financial, geopolitical, etc.—that limit the curators’ ability to work in more sustained and inventive ways. Probably the initial idea of Manifesta’s organizers was to invite professionals from outside the field of contemporary art to curate (or “mediate”) in order to stimulate experimentation and break thorough the bureaucratization and professionalization of creative processes. But the result is a situation in which viewers get a more “biennalian” (as in more conventional) biennial than average that repeats clichés from the past. To break the rules, one either needs to know them very well or not to know them at all, otherwise there is a risk of being caught in the position of the diligent student who wants to perform exceptionally well, but is only capable of grasping the authorities’ expectations.

Despite the difficult economic and political situation in Italy and particularly in Sicily, Manifesta 12 lacks sharp critical statements—very few projects refer to the history of the island or its present state of affairs. Both Orlando and the biennial’s curators are right to invoke Sicily as a place where different religions, peoples, and cultures have coexisted—but the same could have been said of the past history of Venice, or of present-day cities as New York and Hong Kong. What matters is the place accorded to a particular city and region in the current political and economic conjuncture. Viewers will learn virtually nothing about these things at Manifesta 12, just as they won’t find out what made Sicily what it is today. The biennial never goes beyond pretty rhetoric and a short list of trendy topics.

Rhetoric needs narration. Manifesta 12 is chockablock with narrative art of the worst kind. The art community is forced to focus on talking heads, albeit only for the five months the biennial lasts. It is hard to identify the cause of this state of affairs. Perhaps it is a conscious gesture of the curators, who have wholly rejected traditional mediums of art (there is not a single contemporary painting or sculpture in the show) in order to criticize their possible entertainment and market values. But research-based and narrative-driven art did not emerge the other day. These, too, have their strong and weak sides and therefore cannot be considered fresh, self-sustaining gestures in and of themselves.

After the previous two Manifestas, which sold their souls to the devils of big budgets and big museums, turning the project into just another European biennale, the Palermo edition has attracted great interest. But Manifesta 12’s true place in the contemporary art world can be gauged by perusing its website—right until the opening day, there was nothing on it except the times of the preview and official opening parties. There wasn’t even a map of the venues. But there was a wealth of information on how to travel with maximum comfort from Basel to Palermo, for those who had decided to take in the preview of the world’s premier art fair before venturing off to Sicily for what was once the main experimental biennale of the Old World. And unlike in 2016, this year art connoisseurs had to leave the confines of Switzerland for a short spell.

Translated from the Russian by Thomas Campbell. An earlier version of this essay in Russian was first published on redmuseum.church