A man wearing pajamas and a bathrobe clutches a branded coffee mug and ponders the distance through the drawn curtains of the Museo Jumex terrace gallery window, his graying eyebrows knitted in maudlin unease. This is Mike, artist Michael Smith’s alter-ego who in the exhibition at Jumex, “Imagine the view from here!,” considers buying a “curated timeshare living experience” at the museum, marketed by the fictional International Trade and Enrichment Association. In promotional videos and trade fair–like booths, his bone-dry humor critiques the private interests that have a stake in the promotion of Mexico’s contemporary art scene to foreign and local markets as well as the clichéd banality of its consumption.

The show is particularly resonant in the context of Art Week CDMX, the annual week of cultural offerings organized to coincide with Mexico City’s art fairs. Playfully seeding his fictional timeshare with coopted real elements such as photos from past museum events, the omnipresent juice at the museum’s openings, and cameos by the museum’s curator, Smith constructs a conceptual art version of an investable real estate lifestyle package. The show’s trade-fair aesthetic is a reminder of how easy it is to harrumph fairs as too mercantile, too convention center ticky-tacky, but it also calls to mind the ways in which for decades the public coffers backed private interest to encourage Mexican soft power vis-à-vis contemporary art, a policy standpoint that appears decidedly ceased as part of the reforms initiated by Andrés Manuel López Obrador, or AMLO, the new Mexican President.

In its 16th year, Zona Maco seemed the most affected of the three fairs by the economic uncertainty provoked by AMLO upending political orders. This, combined with a global questioning the viability of art fairs in general and Frieze LA launching days later, was cited by many as a struggle-inducing accumulation of challenges. In comparison, Material Art Fair had upbeat energy and fresh, if somewhat similar, presentations by young to mid-size galleries and emerging artists. Its smaller size in an art deco building in front of the Monument to the Revolution kept the fair focused and grounded in local context. Salon Acme, meanwhile, was fun, but it was hard to escape the reminders that branded partnerships were picking up the event production tab that emerging art couldn’t cover.

With the big-name commercial spaces responding to the low-grade market tension by playing it straight, bankable, and Instagramable, the most challenging work was ever so slightly off the beaten path. Ana Segovia’s exhibition “Toy Boy” at Karen Huber Gallery offered gender-queer, candy-colored figure paintings with almost cinematic framing that, through collapsing spatial plains, patterns, and breadcrumb-like trails of surreal symbols, build into psycho-sexual dreamscapes that suggest alternative or parallel realities. At Fundación Marso (co-presented with São Paulo’s gallery Vermelho) “De fábulas y telones” [Of Fables and Curtains] by Tania Candiani further contributed to the sense of haunting landscapes, with the installation Cuatro Telones [Four Curtains] (2018) and the video El principio, el paréntesis y el fin, el telón [The Beginning, the Parenthesis and the End, the Curtain] (2018), in which the camera seems to haunt the folds and tucks of stone curtain statuary. At Arróniz gallery, Christian Camacho presented “The Dream and the Underworld,” a show of small surreal assemblages inspired by “the shadow” of dream logic and narratives which, in their lack of rational sense, felt fitting to now.

A number of independent projects rose to the challenge of presenting work outside of traditional commercial models for the out-of-town audiences, an invigorating sign since in recent years the number of alternative and artist-run art spaces in Mexico City had begun to decline. If by volume of artists alone, foremost among these was “Pabellón de las Escaleras” [Pavilion of Stairs] a DIY, artist-produced exhibition featuring works by 102 artists and organized by artist-curator duo Marco Rountree and Alma Saladin, who co-curate exhibitions as roaming gallery Guadalajara 90210. The pair secured temporary occupancy of a five-story former storage facility currently being converted into luxury apartments. The raw space featured a number of cardiac-arrest-inducing improvised stairs that gave the project its name and serve as a curatorial thread loosely meandering through an ad hoc gathering of objects and architectural intercessions. With works in different mediums and proportions, including Marek Wolfryd’s Modelo para mausoleo de artistas y arquitectos [Model for a Mausoleum of Artists and Architects] (2019), five towering stacks of colored pizza boxes referring to Luis Barragan’s 1958 iconic sculpture Torres de Satélite [Satellite Towers]; a packed-earth reverse pyramid (Bajo Tierra, 2019) built into the ground by architectonic design studio PALMA; and an oscillating fan that played five recorders with its movements (A Suitable Song for a Final Defeat, 2017) by Mauricio Alejo, to name a few, the exhibition quickly registered as an informal index of emerging to midcareer artists and architects working in the city.

Across town, the same duo presented another independent project at the Anahuacalli Museum, which houses Diego Rivera’s personal collection of Pre-Columbian artifacts. Curated by Saladin and Daniel Garza Usabiaga and spanning three floors as well as the observation terrace, Rountree’s solo exhibition “Escuela de Ciencias y Artesanías del Volcán Xitle” [School of Sciences and Crafts of the Xitle Volcano] includes interventions that conceive of the museum as a pedagogical instrument. Outside, a school chair is placed under a palapa, allowing the sitter to take in the mausoleum-like building. Inside, vinyl decals appropriated from a drawing book based on Mesoamerican design were staged around sculptures from the museum’s collection to suggest talkative animation among the artifacts. Pencil drawings and cut paper images of protractors and pencils were collaged into glass vitrines of small pre-Columbian figures alluding to the figures’ utilitarian function. On the roof of a nearby building, colorful broken glass formed the image of a colossal serpent eating its own tail.

At Colégio Dante Alighieri, a former school in Colonia Escandón which is also slated for a real estate conversion, the developers have temporarily rented the building to artists and artist-run spaces while they presumably await permit approvals. Here, visitors can find spaces including Ladrón, Obrera Central, La Verdi, and RRD, as well as the newly launched LAR, a nonprofit dedicated to showing work by female-identifying artists. LAR’s second show, “Bliss,” curated by founder Nika Chilwich in collaboration with Eva Posas and Chloé Wilcox, sees the gallery staged as an improvised beauty salon, bringing together work by nine artists to tease notions of the construction of feminine identity inspired by informal dialogues facilitated by the dynamics of beauty bars.

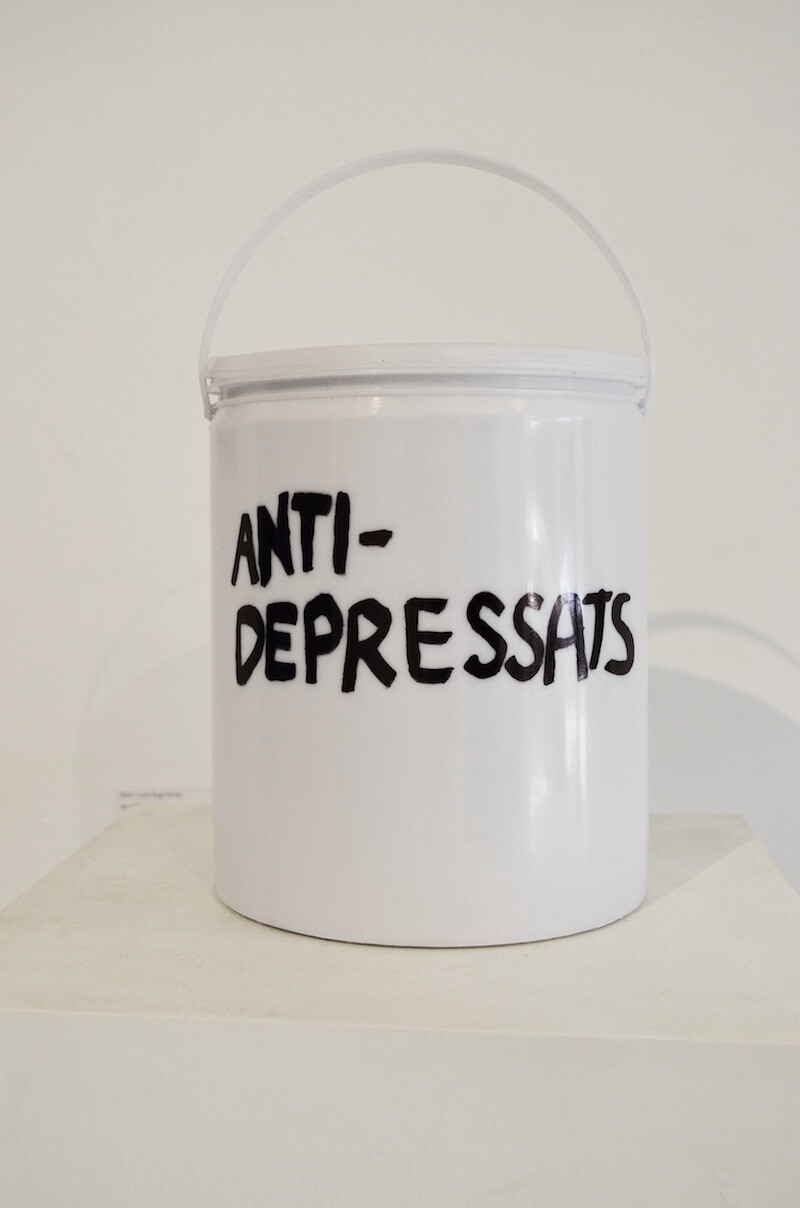

If joy is any measure, then perhaps Salón Silicón was the most satisfying presentation at the end of Art Week. An artist-run independent space housed in a former drycleaner, Salón Silicón responded directly to the context of fair season with their second annual Galerías Similares—a riff on the ubiquitous local chain Farmacias Similares, which sells generic medications—a salon-style exhibition of anonymously produced homages to works by famous artists. With works like cigarette-covered beer cans by “Sara Lucas Similar” or a gallon paint bucket labeled “antidepressants” by “David Shrigley Similar” at “up to 90 percent off” it comically played with the aura of speculation inherent to alternative spaces and emerging artists. Clearly not expecting to make a buck, but happy if they do, the spirit of Galerías Similares is a reminder of the legacy of crust, grit, and humor that has informed Mexico City’s project spaces since at least the 1990s.

Speculation and investment are ultimately about buying into an idea of the future. Whether it’s Mike taking a stake in a fictional Jumex timeshare, government investment in culture, developers offering space to artists, or galleries buying into a fair, each decision signals commitment to a set of belief-based, reality-shaping parameters. The uncertainty that seems to be starting to permeate market conviction is probably overdue, but like the serpent eating its tail, it will all go round again.