The works on view in this group show, in which several contemporary artists respond to the legacy of Harlem Renaissance-era painter Aaron Douglas, are united by a Black existential affinity with literature and the natural environment. The exhibition is constructed around four works by Douglas from the museum’s Walter and Linda Evans Collection of African American Art that center two of his key interlocutors: James Weldon Johnson and Langston Hughes. Three are illustrations to Johnson’s poetry collection God’s Trombones (1927), a striking articulation of religious oratory, while the fourth illustrates Hughes’s poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” (1921), and accompanied its original publication in The Crisis. It’s a poem that Black folks have long held as a psalm, its closing lines reverberating across generations— I’ve known rivers: / Ancient, dusky rivers. / My soul has grown deep like the rivers. This meeting of Black thought, art, and letters—a history of cross-disciplinary connection—sets the stage for the contemporary works in the show, and guides the exhibition’s curatorial framework.

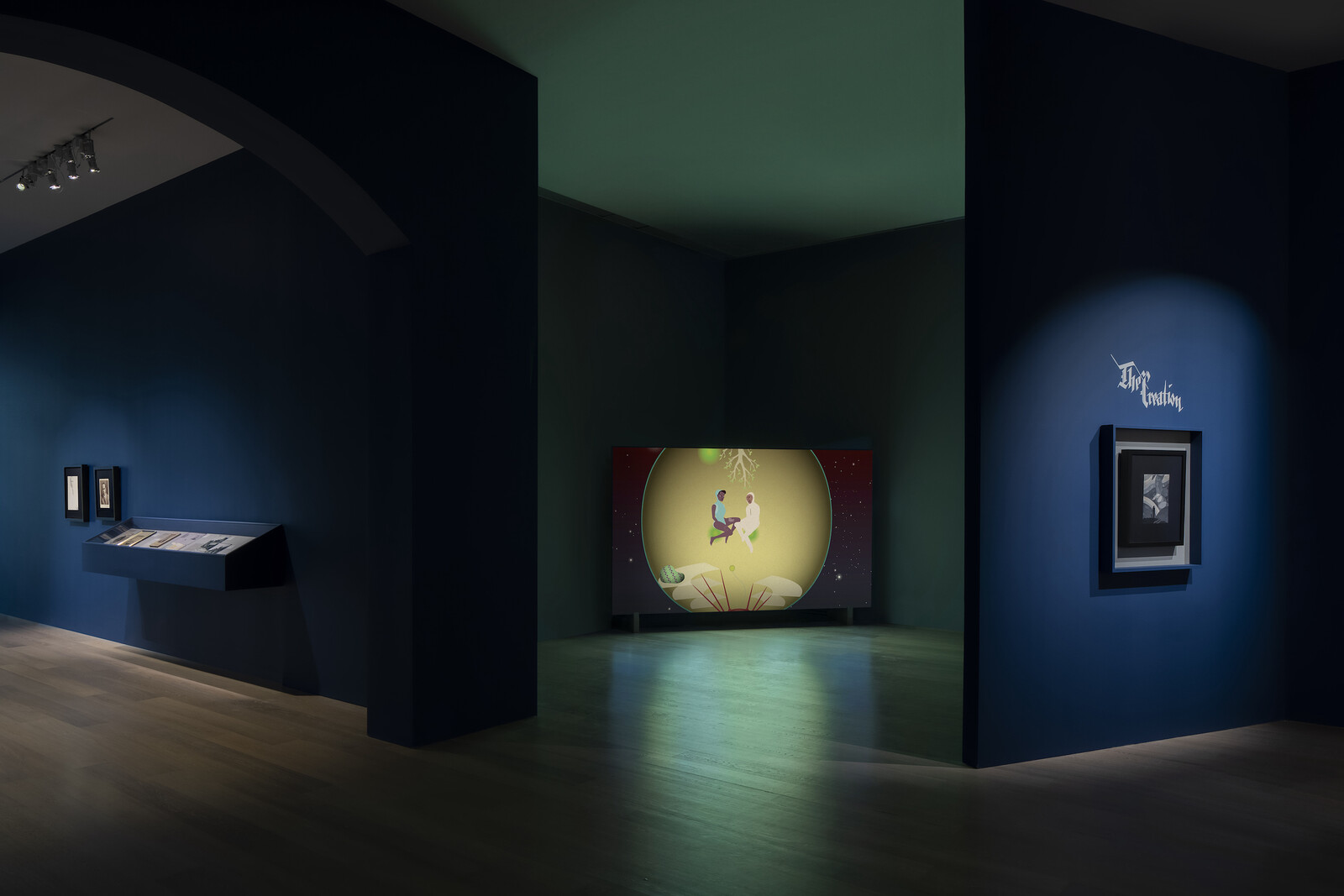

The gallery is dimly lit, with a humming cacophony of sounds and dancing imagery bleeding between the gallery’s archways from four stand-out video works. A commissioned piece by Akeema-Zane and Rena Anakwe, Our Mourning Due — A Funeral Sermon (2022), weaves together fragments of performance, writing, and an experimental electronic sound design. The imagery glitches across the screen as the scenes are set in motion and layered as if by a ghostly kaleidoscope: flashing glimpses of the sky, a horse stable, the interior of a church, the rushing waves of the sea, and sun-blanched rocks. The glowing use of mirroring devices and the sighting of inverted figures and landscapes is actively immersive. Much of the textual score is original, with excerpts from Johnson’s “Go Down Death” (1927) compounding a critical focus on ancestral exchanges and the Anthropocene: “Let the mouth of the seas smite us to surrender / that we may grasp the deep significance of crisis.” The piece’s vocal line pulls viewers into a melodic descent, not toward resignation, but into a spiritual register of interconnection—an invitation to reset thorough remembrance and reckoning.

Allison Janae Hamilton’s video work Wacissa (2019) is also based in environmental abstraction. Wacissa is a river in Florida that leads into the Gulf. It is a wild and remote waterway that boasts more than a dozen springs and the historic Wacissa Slave Canal, including dams and commercial trade remnants constructed by enslaved people. This ecosystem is the billowing focal point of Hamilton’s piece, which features a gliding underwater view of the river. The orientation is spectacular: the camera’s shallow immersion in the river’s skin casts the flora along the horizon as the device is submerged at a slant. There are moments when the camera lifts to the surface, creating a distorted perception of the surrounding woodlands. The journey through the river is paired with a gurgling natural soundscape of steady movement underwater. The effect is similar to the sound you hear when you place your ear to someone’s belly, or the muffled quiet that floods your senses when floating in the ocean— sparking curiosity, anticipation, and an obscure calm.

Douglas’s work tends to place Black figures within effervescent landscapes of enlightenment, resistance, and cultural history; these motifs are carried throughout all the video pieces on show. Afua Richardson’s Blood & Water: The Negro Speaks of Rivers by Langston Hughes (2014) is a series of graphic illustrations in monochromatic gray tones with accented warm colors, setting the stanzas of Hughes’s poem to a series of Afro-speculative comic scenes that map Black life before the trans-Atlantic slave trade. An undulating sonic score by Waking Astronomer, a musical trio of which Richardson is a member, wraps the drawings in a contemporary up-tempo countermelody.

The curatorial decision to emphasize video works is anchored in historical context. Upon entering the gallery, visitors are met with a rare film by actor and filmmaker Spencer Williams Jr. who responded to Johnson’s collection of literary sermons with the production of a trilogy of religious race films. On view is an excerpt of Go Down, Death! The Story of Jesus and the Devil (1945), which screened in Savannah upon release, an anchor to the cross-generational and mostly southern artmaking on display. The exhibition leaves visitors with a striking salutation: let us pray and mourn in peace.