Go past the Tiffany glass, the inventory of deco design and the wing of feminist art that still bears the name Sackler, and finally, tucked away, you’ll find a small enclave of two rooms comprising Suneil Sanzgiri’s solo institutional debut, “Here the Earth Grows Gold.” The smaller of these galleries contains: a sculpture, Red Clay, Stretched Water (Return to the Source) (all works 2023), a kind of provisional hut built of black bamboo and printed images; a minute-long loop of 16mm film, My Memory Is Again in the Way of Your History (After Agha Shahid Ali), in which a digitally-animated banner reading “Your History Gets In The Way Of My Memory” flutters atop waves; and quite a lot of wall text (the one written by the artist himself, demanding that the Brooklyn Museum divest itself of various ill-gotten items in its collection, might reasonably be taken as the show’s fourth work). Moving through a curtain to the centerpiece, the digital double-projection Two Refusals (Would We Recognize Ourselves Unbroken?), maybe the first thing you notice is the gap between its screens: each canted slightly off an unseen wall, they funnel vision to the six inches or so of space between them.

Why are they arranged this way? It doesn’t seem merely practical, so what’s happening in that black band? Sanzgiri, mercifully, is not such a literal artist that this reads as a single screen broken. Or perhaps he is, to the extent that today’s “political art”—which Two Refusals surely is—seems obliged to concern itself with the question of popular legibility, of clear communication. But to be concerned with that question is not to respond in the uncomplicated affirmative; I’ll risk that this is one of the gaps between art and political action, and that this is at least in part what his screen-based installation figures.

That figuration is basically rhythmic: across the film’s 36 minutes, Sanzgiri makes use of the full array of potential relations this setup affords, shifting between single images that sprawl across both frames, contrasts between the two (whether in form or content), and alternate views of the same scene. The montage is dense, though measured, as it draws together a wider historical field than the films comprising his earlier “Barobar Jagtana” trilogy (2019–21), each of which is anchored to a relatively tight thematic-conceptual core. Still, Sanzgiri’s concerns remain consistent: the past and present of struggles against colonialism; the capacity of individual histories to express broader truths of collective experience; the endurance and elaboration of myth; the various captures of the world by the technical.

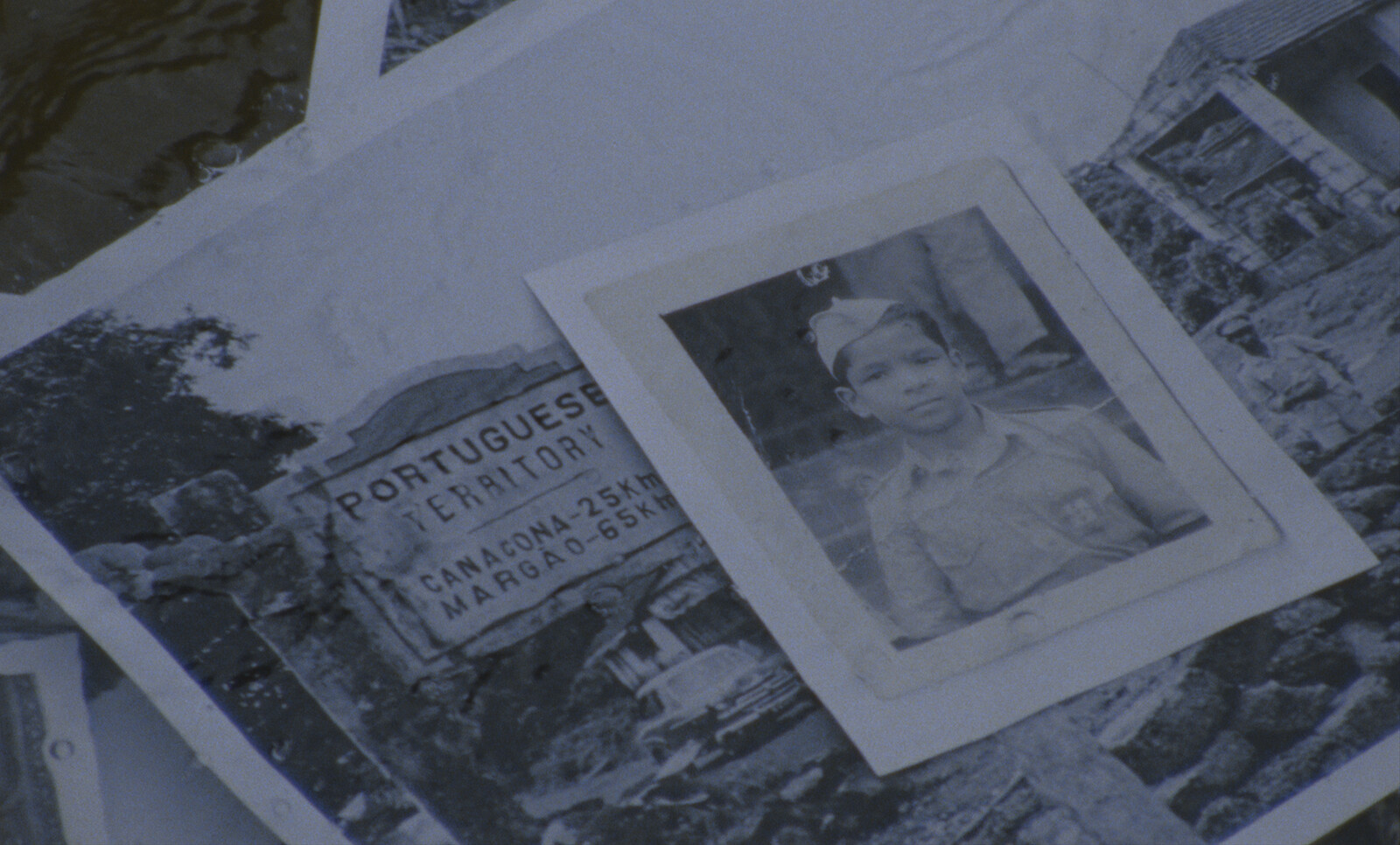

If the tone of that last sentence, its implication of heady and high-flown ambition, seems to me adequate to Sanzgiri’s prior work, it fails to express the remarkably casual manner with which Two Refusals weaves its disparate pieces. Across six chapters, Sanzgiri pulls at a range of threads relating to as many centuries of Portuguese colonialism across Africa and the Indian subcontinent. In the first, Adamastor, the storm-borne monster of Camões’s Os Lusíadas (1572)—a mythological character created to express the indomitable will of Portugal’s explorers, he was said to have kept sailors from rounding the Cape of Good Hope since the time of ancient gods—appears to a woman in a dream, and to us as digitally animated roil of black clouds. She wonders, in the first instance of a voiceover written by the poet Sham-e-Ali Nayeem, what might have been had he not failed to stop the ships of Vasco de Gama.

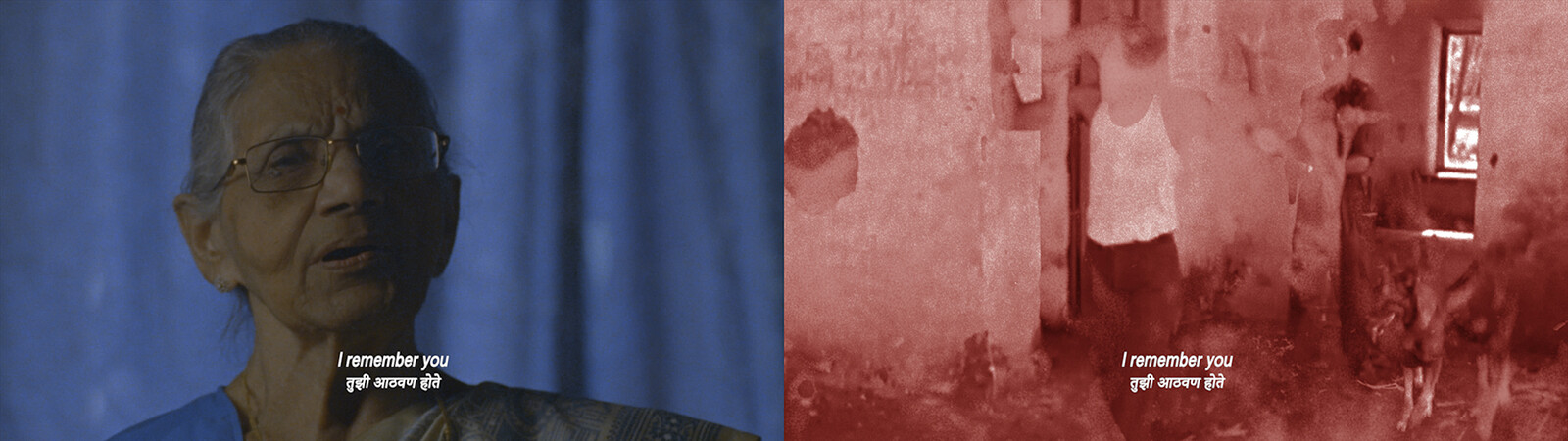

This melancholy persists across what follows, an undercurrent at once acknowledged and refused. The four chapters comprising the main body of the film narrow in on two sites of struggle—Goa and Angola—and then widen to take stock of the flows of anticolonial energy and organization passing in and around them. As with his exhaustion of rhythmic possibilities, Sanzgiri makes use of as wide a range of footage as possible, bringing together his own Super 16mm photography with both fictional and documentary archival footage, much of which has been subjected to extensive intervention: direct animation, heavy tinting, and so on. Two militant women emerge as central characters: the still-living Goan freedom fighter Sharada Sawaikar and the Goan-Angolan communist organizer Sita Valles, murdered by the Angolan government after having helped the country secure its freedom. Sawaikar, interviewed for the film, provides its most moving and brutal moments, as she recounts both her torture and her belief: “Goa’s parent was India and no one else. So I called out to her, in the form of a song. If someone can make it reach India, so be it.”

From those words, Sanzgiri cuts first to archival footage of a meeting of Indian militants: “The people of Goa […] think the Indians have forgotten them. So, we will have to change our methods.” And then, to the opening dreamer driving a motorcycle down a country highway, as her voice returns on the soundtrack: “Nation isn’t mother.” In the emotive and intellectual movement across these passages, there is something like a theory of history, a sensitivity to the distance between things which appear similar, continuous, or even identical, and an understanding of what art might be capable of contributing to the cause of political struggle. Valles’s brother Edgar speaks over the image of headlights barely illuminating the road ahead: “We thought it was possible to change the world, and to get a new world.”

In isolation, this recollection from Valles’s brother Edgar might seem to speak, with its pointed past tense, to a kind of revolutionary nostalgia, a self-defeating melancholy of the left. But Sanzgiri’s use of it—its specific pairing with images of headlights barely illuminating the road ahead and its broader resonance with the film as a whole—draws out a different aspect, one in line with the militant demand above. Within living memory it was possible to believe in the proximity of a new world. Faced with the horrors of our own moment, as colonial and post-colonial dynamics descend into the genocidal—as in the cases of Israel and Myanmar, both currently on trial against such charges before the International Court of Justice, but also for the millions suffering from the effects of climate catastrophe (if the waters which recur through the show are overtly symbols of flows of revolutionary energy, they cannot help but express a certain doom as well)—Sanzgiri’s film insists that while learning from the past is necessary, it is not enough: we will have to go on changing our methods if we are to achieve such belief at the scale this world demands.