In 1945, Hassan Fathy, an Egyptian modernist architect and pioneer of sustainable design, was tasked with relocating 7000 residents from the village of Gourna, on the West Bank of the Nile, to a new site several miles away. The original town of Gourna was built on top of a tomb that residents had been illegally raiding to support the local economy for generations; eventually, government authorities commissioned the massive rehousing project in order to preserve what was left of these artifacts.

In his 1969 book Architecture for the Poor: An Experiment in Rural Egypt, Fathy describes the daunting task of creating the entirely new municipality of New Gourna: “All these people, related in a complex web of blood and marriage ties, with their habits and prejudices, their friendships and their feuds—a delicately balanced social organism intimately integrated with the topography, with the very bricks and timber of the village—this whole society had, as it were, to be dismantled and put together again in another setting. […] It was uncanny enough that a whole village should be projected without reference to the State Building Department, but it was even more unnerving to find myself with the sole responsibility for creating this village.”1

Fathy idealistically built New Gourna using local materials like mud bricks and design principles that would now be described as akin to permaculture, ultimately creating a carefully laid-out settlement that he hoped would be cleaner, healthier, and more beautiful than the cramped quarters of the original Gourna. But his project ultimately failed and New Gourna was “never popular with residents, who felt forced to adapt to a new, prescribed environment.”2 Instead, most residents chose to live in the sprawling outskirts of Luxor, a neighboring city on the other side of the Nile.

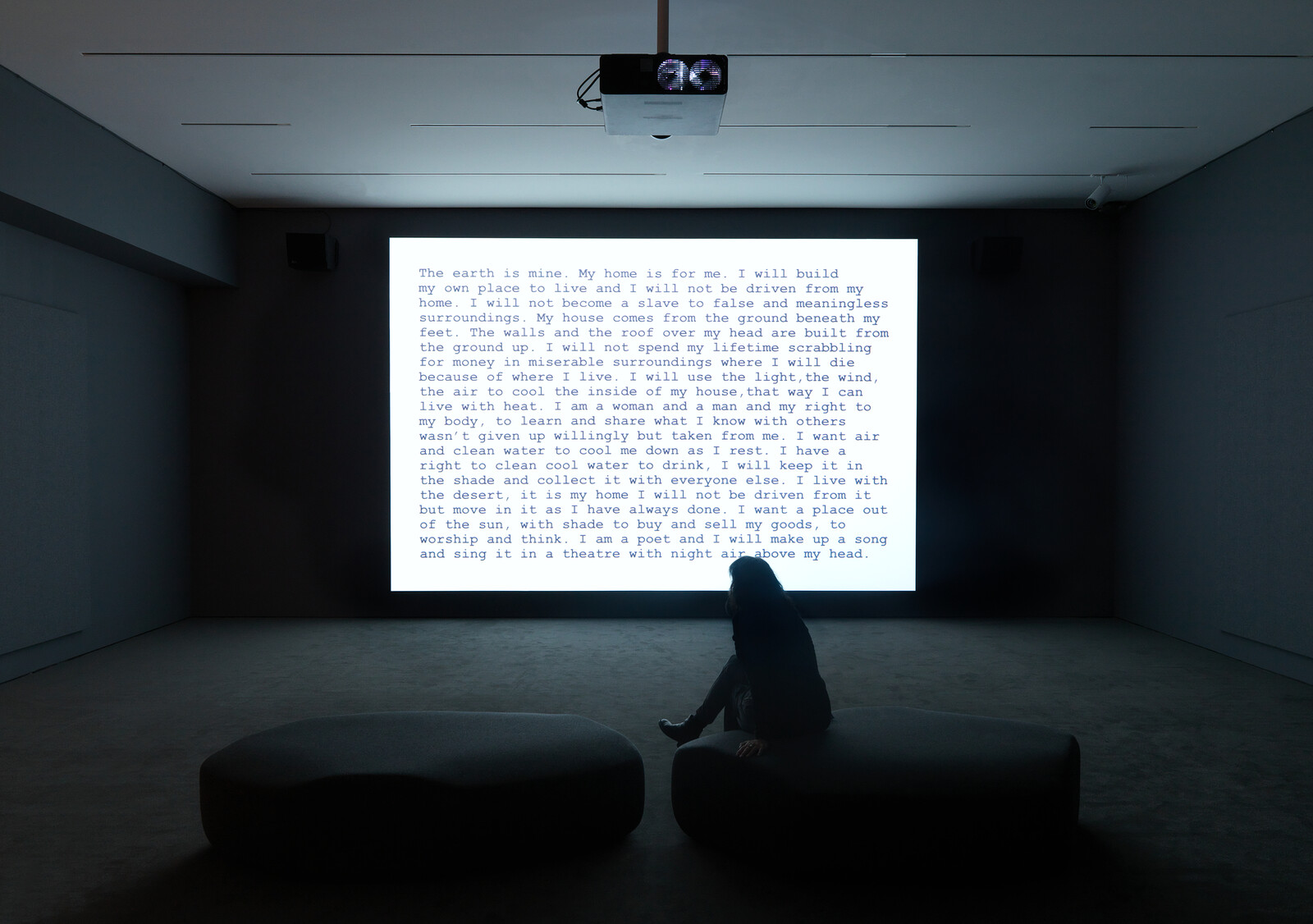

New Gourna and New Baris, another mud brick town Fathy was commissioned to create and that was also eventually abandoned, are the subject of Hannah Collins’s exhibition “I Will Make Up a Song” at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Collins presents her subjects—architecture, humans, and animals—through large-format photographs screened sequentially as an immersive video installation. This central video, I will make up a song and sing it in a theatre with the night air above my head (2018), comprises photographs of the two villages, blown up to monumental size and accompanied by an abstract soundtrack created by musician Duncan Bellamy. In a smaller adjoining gallery, an enormous, wall-sized photograph of an Egyptian temple in the original Gourna contextualizes these images in terms of architectural scale.

Most of the images in the video are devoid of living figures, featuring empty doorways and courtyards or long shots of Fathy’s avant-garde constructions, which sometimes border on the science fictional, such as an otherwise traditional mud brick building featuring half-cylindrical domes on the roof, designed for increased air circulation and cooling. The use of still photographs mounted in a format associated with moving images emphasizes the uncanny quietness of these spaces. Other photographs feature the remaining citizens of New Gourna, including images of children using in-between spaces like empty courtyards and entryways for impromptu games, or animals nesting in the scant shade cast by low adobe walls. Details like a naked fluorescent light bulb dangling in an elegant arched window are reminders of the deeply haphazard and unpredictable ways in which people actually live, in comparison to the ideals of architects. Spliced between these photographs is a typewritten text written by Collins and told in the first person, describing the universal need for housing, clean water, air, and a place “to worship and to think.” It ends with a suggestion about the need for aesthetic autonomy: “I am a poet and I will make up a song and sing it in a theatre with the night air above my head.”

The principles of sustainability behind Fathy’s failed utopias, as well as their shortcomings in terms of creating places where people would choose to live, are deeply aligned with Collins’s longstanding interest in the ways that individuals are caught up in the worlds that interpolate them, and the contingent ways that they world-build themselves. Her commitment to thinking seriously about the materials and structures that constitute and support our lives is directly connected to questions about how humans can make a home for themselves and a livable world for one another.

Hassan Fathy, Architecture for the Poor: An Experiment in Rural Egypt (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973), 17.

Wall label, Hannah Collins, “I Will Make Up a Song” at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), San Francisco, 2019.