Organized by the transdisciplinary ORTA collective and based on the writings of Kazakhstani artist, writer, and inventor Sergey Kalmykov (1891–1967), the Kazakhstan Pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale comprises immersive scenography made from the simplest materials. When I visited during the opening days, grayish wrapping paper enveloped the space from floor to ceiling, providing a background to printouts and props covered in aluminum foil and activated by participatory performances that the collective call “spectacular experiments.” This is the first year that Kazakhstan has participated in the Venice Biennale on its own, and the same goes for Uzbekistan and the Kyrgyz Republic: since 2005, these countries have shown as part of the Central Asian Pavilion.1

Ten days before the opening of the biennale, ORTA realized that the long-planned delivery of artworks and materials from Kazakhstan would not arrive in time.2 The war in Ukraine meant that trucks that would usually cross Russia and Belarus—including those from Kazakhstan—were being rerouted through Georgia and Azerbaijan. This not only rendered visible the often-hidden logistical and financial efforts that organizers have to go through, pointing to the extreme inequality at the very foundation of the national pavilion format, but also made the pavilion a makeshift laboratory for social experiment—one as fragile and sincere as the idea behind it. Rather than delay their exhibition, ORTA decided to source materials for the installation locally, and to gradually install the exhibition as originally intended as artworks arrived over the following month.

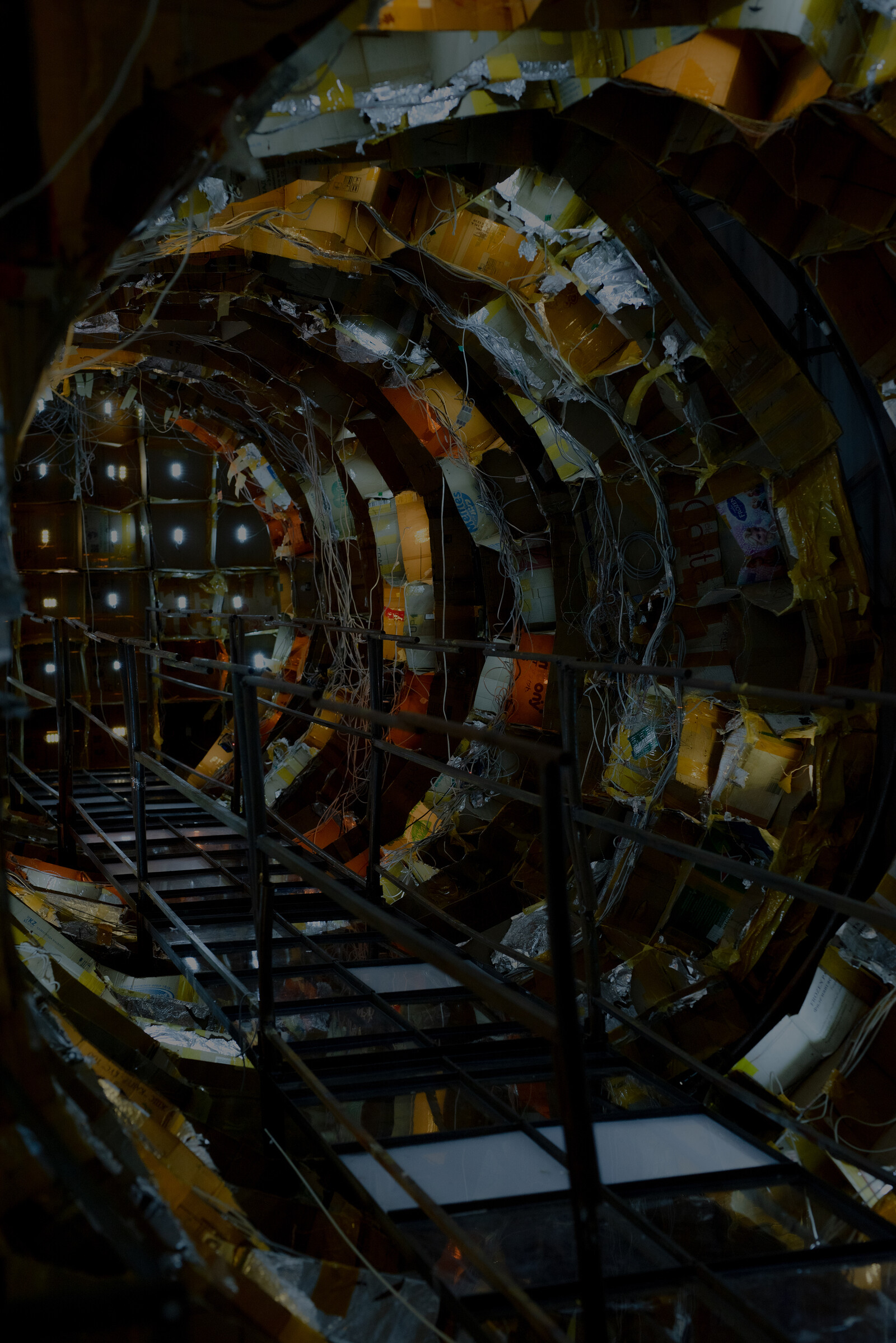

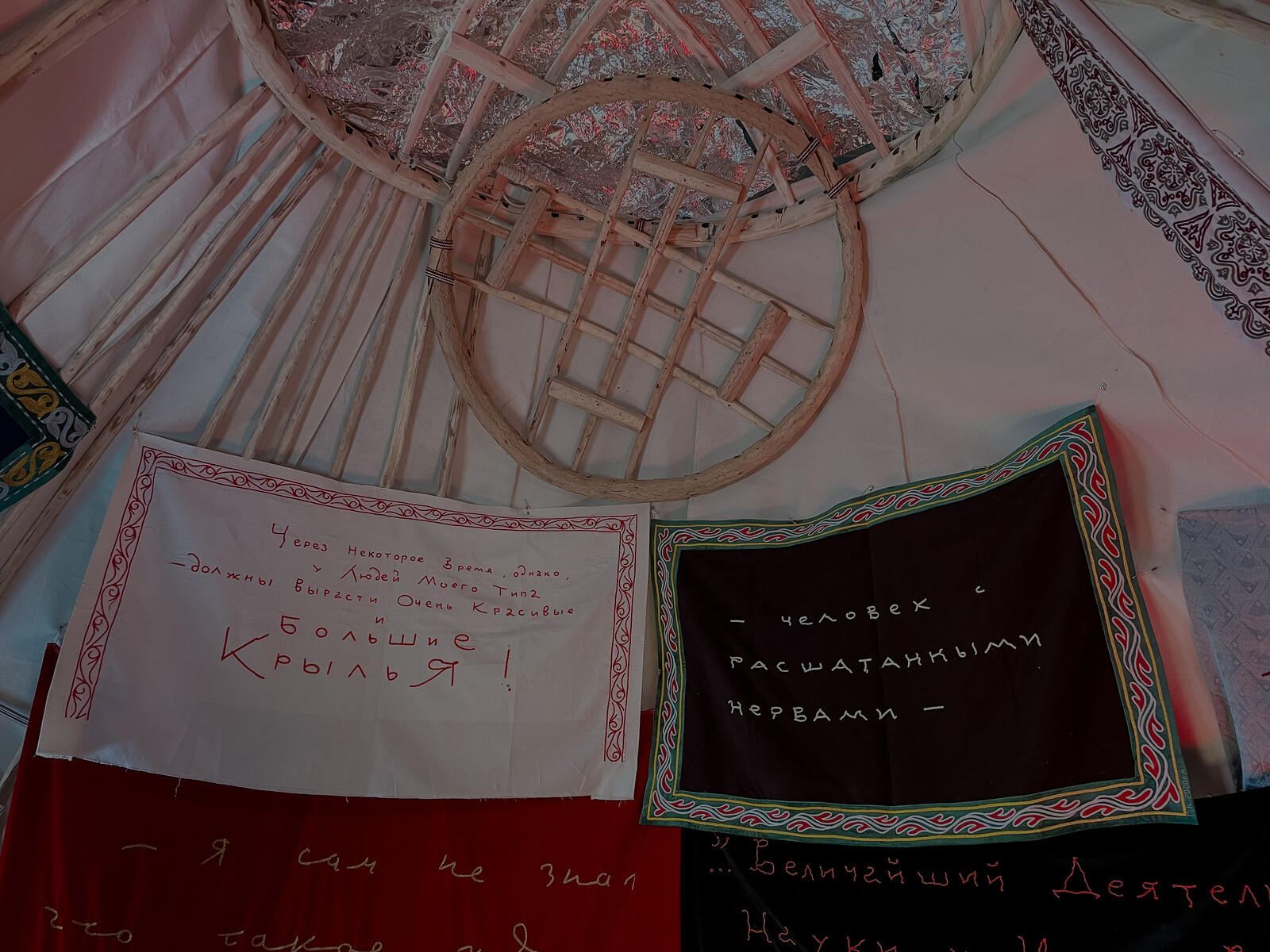

So it was that long scraps of aluminum foil, moving lightly in the breeze, hung over the open doorway to the pavilion during its opening days. After crossing this threshold, visitors were warmly welcomed by a female performer who guided us to read a written precis of the performance that was to follow—a playful yet sincere invitation to spend time in the space, which resembled a DIY spaceship, and take part in a roughly half hour-long performance. The pavilion, called “LAI-PI-CHU-PLEE-LAPA Center for the New Genius,” is the most recent example of ORTA’s longstanding engagement with an artist who was born in Samarkand and educated and employed in St. Petersburg and Moscow, where Kalmykov belonged to the studio of painters Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin and Mstislav Dobuzhinsky.

In the 1930s, Kalmykov came to Almaty to work as a set designer at the Kazakh Musical Opera and Ballet Theater and continued to make art which, because not aligned with the state socialist cultural policies, he rarely showed in public. Instead, he worked ceaselessly in private, creating an alternative world featuring characters both real and invented, from an imaginary daughter to Leonardo Da Vinci. He painted in many styles, from abstraction to surrealism, and likewise experimented with literary form. Declaring himself a “Genius of the First Rank of the Absolute Interplanetary Category,” he was known in Almaty for his eccentric style, wandering the capital’s streets and sharing his ideas with whoever would listen. Towards the end of his life, he was forced into a psychiatric clinic—a typical method at that time for silencing members of cultural and political movements which did not conform to Soviet orthodoxy.

With this project, ORTA took Kalmykov’s interplanetary theory of artistic genius further into the embodied realm of performance. While reading about the various stages of the spectacular experiment, we were given props: a crumpled piece of aluminum we stuck atop our heads with transparent scotch tape, and a brown wrapping paper mantle to be held around us throughout the piece. After crossing into the next room, we sat on foil-wrapped pads placed on the floor. The shiny, retro-futurist robot-sculptures were arranged in a parade formation, directing our gaze towards a woman sitting at the center of the stage. She was embroidering a Venice lion in biz keste—a traditional Kazakh hand embroidery technique.

We listened to our guide read a text by Kalmykov to the accompaniment of changing sounds and lights. The aluminum on our heads served as the transmitter, whilst cardboard mantle was a “protector” for the energies the artists wanted us to engage with. The experience culminated in a collective song of worship, in which we called each other’s names and wished for each of us to become the geniuses we deserved to be. Falling somewhere between a religious ritual and a self-help healing group, the ceremony was transformative, conjuring joy and calmness amidst the biennale’s manic opening days.

ORTA’s collaboration with Kalymkov’s work democratizes the often discredited idea of the genius by flipping it: we don’t come to the pavilion to gaze at the genius of an individual, but to discover our own through a collective experience. Focusing on an artist who never got the recognition he deserved during his lifetime also gives hope to those of us who are struggling to broaden art-historical narratives, making place and space for manifold voices, multiple timelines, and chronologies in different institutional platforms. ORTA’s work with Kalmykov’s legacy is not historical or didactic, but rather embodied and based on collective experience. As such, they make it seem as though Kalmykov is our contemporary, and they are constructing his proposed new reality—his new world—together.

In 2019, a planned and government-backed Kazakhstan pavilion expected to open at Venice was unexpectedly cancelled, in opaque circumstances.

Founded by director Rustem Begenov and actress Alexandra Morozova in Almaty in 2015, ORTA’s current line-up was completed when artists Alexandr Bakanova and Sabina Kuangaliyeva, and photo and video designer Darya Jumelya, joined in 2017.