Each time Moyra Davey speaks in her new film i confess (2019)—spinning a narrative that’s at once autobiographical, political, essayistic—she’s preceded briefly by a faint ghost-voice, anticipatory echo. It’s the sound of the artist’s own voice, prerecorded and playing off her iPhone as in-ear prompt, while she paces her New York studio, repeating the script aloud. Davey has used this subtly deranging method before, in films such as Les Goddesses (2011) and Hemlock Forest (2016). It gives her a halting, spacey presence on screen, as though she’s merely the conduit for personal memory, cultural-political reflections and a shelf’s-worth of citation. In the past, Davey’s films have invoked Anne Sexton, Mary Wollstonecraft, Chantal Akerman, and Derek Jarman. When we first see and hear her in i confess, which is shown alongside a series of photo-etchings, she’s thinking about James Baldwin—a famous 1965 debate with William F. Buckley Jr. plays on YouTube in the background—and about the vexed history of French-Canadian identity.

Davey was born in Toronto in 1958, and grew up in Montreal, where she felt ashamed to be an anglophone outsider, and at the same time terrified of the strictures of Québec Catholicism. Early in i confess she tells us she’s lately been seduced by the prose and passion of the Québécois nationalist writer Pierre Vallières. In the 1960s, he was a philosophically minded leader of the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ): a group whose campaign of bombing, kidnap, and murder culminated in the October Crisis of 1970. The FLQ kidnapped the province’s Deputy Premier Pierre Laporte and a British diplomat, James Cross. Laporte was strangled, and Canada was thrust into a decade and more of wrangling over sovereignty and language. Davey met and photographed Vallières in 1980, by which time he’d retired to a hippie commune and was in a relationship with Davey’s ex-boyfriend.

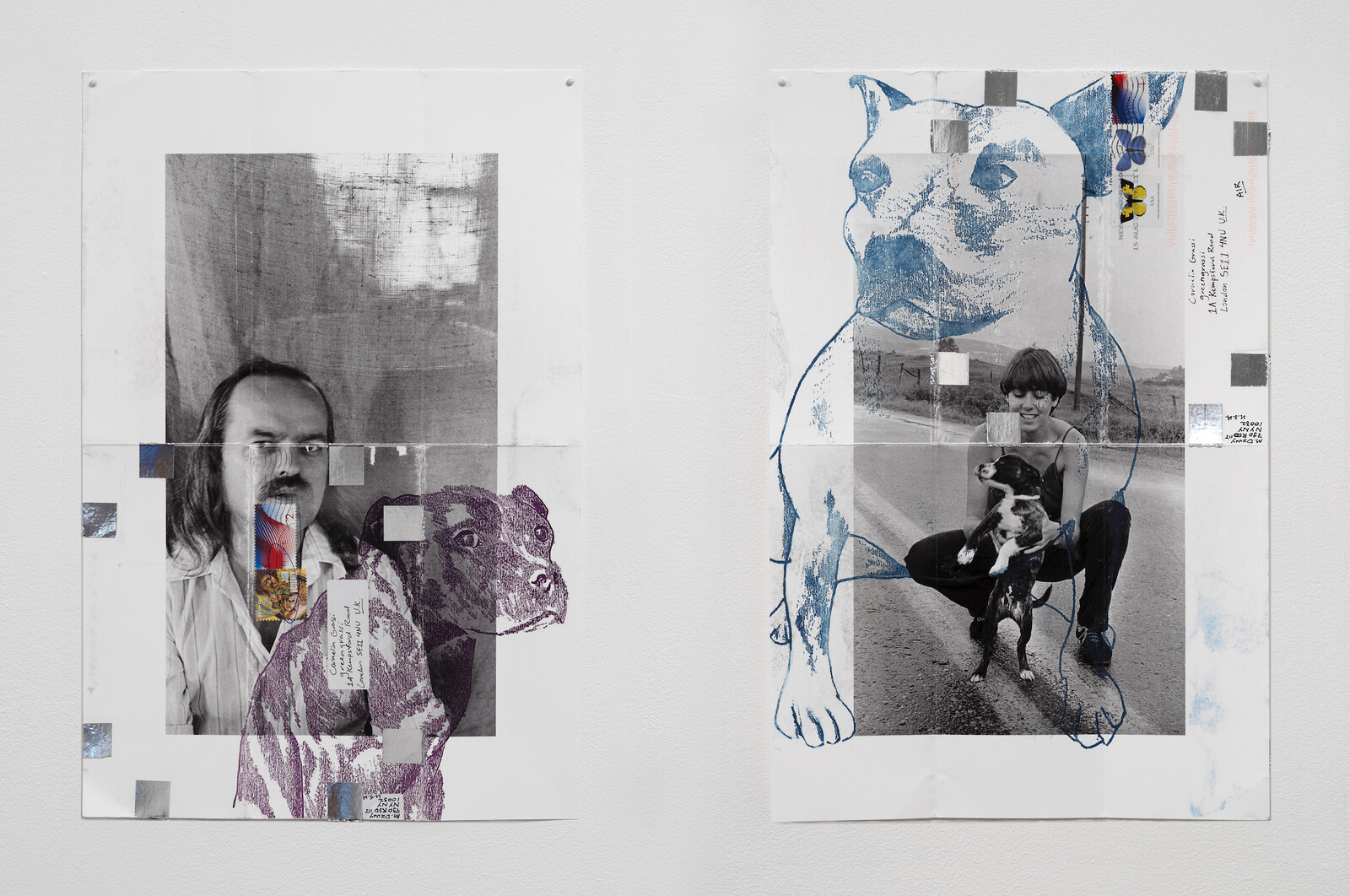

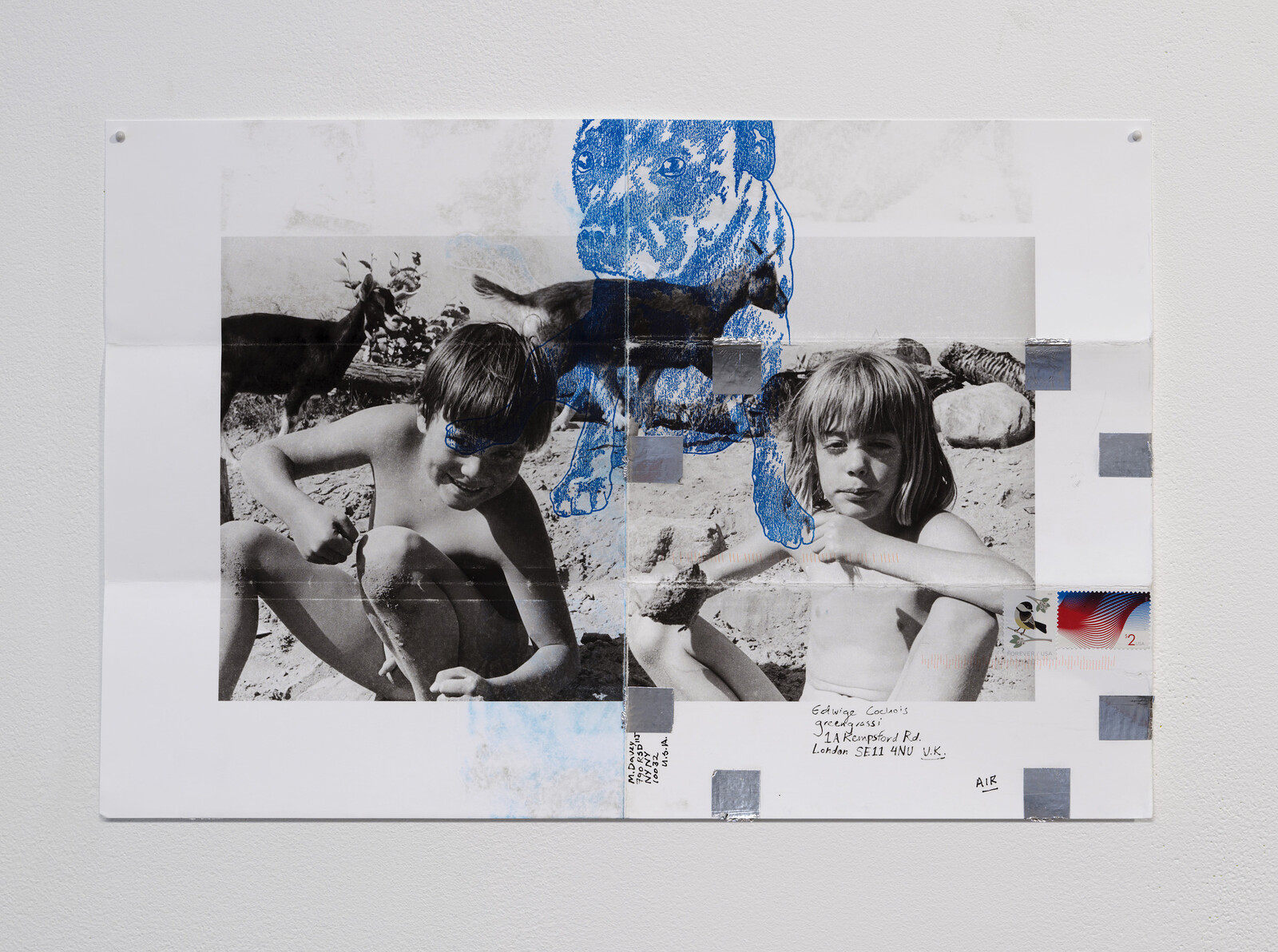

Such histories, intimate and political, manifest amid a shifting star map of studio-bound images and texts. There are the photographs—old prints and contact sheets—that the young, despairing Davey took of Vallières; the fragile edge-colored paperbacks of Baldwin that Davey’s partner has found; close-ups of Catholic-themed entries and illustrations in a Larousse dictionary; and the artist’s hands turning the pages of a copy of Robert Frank’s The Americans (1958)—the book is falling apart at its binding. It all seems drifting, anxious, and retrospective until the film is interrupted by Davey’s encounters (online and in person) with the French-Canadian political philosopher Dalie Giroux, who offers a scathing critique of Vallières’s ideas and legacy. The writer’s solidarity with the poor in Québec is beyond question, she tells Davey; but his politics depended on a racist, unthinking equivalence between white Québécois experience and African-American history.

That the furious complexities of this history may coexist with the textural richness and wry poetics of Davey’s work—this is one of her mysterious achievements. It’s all done according to the drifting logic of the essay, with a style of reflection and reference that is only partly indebted to her literary and cinematic exemplars. The rest is supreme attention to her own modes of attention. The way a text takes hold of her, connects her to other writings and other lives. The messy way that digital technologies—the iPhone and audio recorder, Davey’s studio computers—live beside decades-old photographs and cameras and remnants from a life that can be held in the hand. Not for the first time in Davey’s films—there are similar shots in Les Goddesses—we see her in i confess blowing the dust off her books, starting again the adventure of thought, memory, and making.