This is the first installment in a two-part essay exploring the aesthetics and politics of the representation/abstraction dyad, with the second half to appear later this week.

In late 2022, The New York Review of Books published an essay entitled “Between Abstraction and Representation,” by the veteran art critic Jed Perl.1 Framed as a strangely nostalgic jeremiad, Perl’s text laments the decay of a once-robust opposition between abstraction and representation in visual art. Once, it claims, in the heyday of mid-century Manhattan, a tight-knit cadre of artists and critics agreed to fiercely disagree in a “war of ideas,” where artistic positions amounted to all-in personal, aesthetic, and political commitments; from this battle royale the strongest emerged victorious, thereby enabling a collective evolution of artistic forms. However, Perl argues, in subsequent decades the advent of new hybrid strategies and modes––a grouping loosely termed “postmodernism”––led art to become dangerously complacent and vacuous.

Citing a heterogeneous group of artists including Julie Mehretu, Gerhard Richter, and Simone Leigh, Perl claims that more recent efforts to recombine abstraction and representation have robbed these forms of their autonomy and authority, producing a “muddleheaded eclecticism.” Opposing this process of decline, Perl calls for a return to the quasi-aristocratic virtues of a time when artists and critics would duel by means of their fine-honed sensibilities, as if “nobody doubted that the essential nature of art, the morality and metaphysics of art, hung in the balance.” The overall effect is both absurd and uncanny, almost as if a clever grad student had asked ChatGPT to generate an essay denouncing contemporary art in a neo-Greenbergian style, thereby revealing the conceptual limitations of American liberal art criticism––an institution that is clearly itself in decline yet remains nevertheless influential.

The most obvious of these constraints is a highly dogmatic definition of art in terms of medium, privileging visual art (especially painting) while ignoring media art, conceptualism, performance, and the avant-gardes. Beneath this oversight lies an unquestioned valorization of artistic autonomy, which was of course one of the central planks in the cultural politics of a newly hegemonic US during the Cold War; such a bias fails to grasp the long-documented instrumentalization of that autonomy by institutions including the CIA and MoMA, as well as the many sites across the Global South in which aesthetic and political values were linked in the service of an altogether different autonomy as part of decolonial liberation struggle.2

While Perl’s essay does not adopt a specific metacritical position, its philosophical orientation is clearly post-Kantian in its insistence that individual judgments of taste can be synthesized into a greater, ostensibly liberal democratic common good. Because of this unchecked reliance on an Enlightenment metaphysics that has been subjected to successive waves of radical critique––including from Marxism, gender studies, deconstruction, decolonial theory, and Black study––liberal art criticism has long been unable to resolve basic questions such as those on which Perl’s argument predictably founders.

To put it bluntly, framing abstraction and representation in terms of a conceptually stable, historically consistent binary is flat out untenable, if not actually nonsensical. Not only are abstraction and representation themselves both concepts, i.e. abstractions which Cartesian metaphysics has typically construed in pictorial terms as representations of the world outside the “window” or “mirror” of the mind; they are also both concrete material practices encoded with specific social meanings and enacted by racialized, gendered, and classed subjects under historically contingent power relations, such as those between the imperial metropole and the settler colony.3 Within such conjunctures the differences between abstraction and representation can become radically undecidable, such that in certain cases their relation becomes something like a quantum entanglement, rather than a dialectical contradiction, let alone a simple opposition. When art criticism ignores this fundamental aporia, it loses contact with the ways in which artists have often much more accurately understood the complex web of reciprocal action between the forms typically framed in hugely distorting terms as a simple and consistent opposition between “representational” and “abstract.”

It is hardly as if the limitations of liberal American art criticism are news at this point, but a small coterie of New York-based critics like Perl, Roberta Smith, Jerry Saltz, Robert Hughes, and the recently deceased Peter Schjeldahl has long had––and continues to have––a disproportionate impact over mainstream art discourse. What’s more, the stakes of critical questions like Perl’s go well beyond influence, reputation, or public opinion. Despite its manifest shortcomings, Perl’s essay is correct that the relation between abstraction and representation has changed massively (and any number of times) since the effective institutionalization of modernism in the years after 1945.

That said, if we want to properly understand these changes, we can’t be satisfied with wan, bloodless dismissals of stylistic pluralism––especially when these criticisms are directed, as they too often are, at female, LGBTQ+, and/or BIPOC artists with the implication that their work is the subject of political fashions and isn’t worth taking seriously. Instead, we need to demand modes of critical responsiveness that can track the contingent interaction of aesthetic modes (e.g. representation, abstraction, and their many entanglements) in terms of their relation to discursive and institutional structures of signification, hegemonic modes of subjectivation, and the ever-mutating determinations of neoliberal capital.

Toward that end, this text analyzes examples of recent critical practice that productively complicate the aesthetics and politics of the representation/abstraction dyad. It considers cases in which artists and curators have resisted the kind of binarizing, Cold War-era friend-enemy distinction for which Perl waxes so weirdly nostalgic, and has instead insisted on more nuanced and generative modes of engagement. One core hypothesis is that we should understand these shifts in terms of a productive resistance to representationalism––a term with specific usages in philosophy, but which functions here in a non-academic sense to denote a set of ideologically determined assumptions about how different modes of representation necessarily pertain to subjective experience, artistic form, and political action. (These meanings will be elaborated in more detail below; for now, suffice it to say that representationalism describes any instance in which the conceptual and/or sensate complexities of art and politics are effectively weakened into dogmas or formulae.)

By gauging the dynamics of such relations, we can begin to see how the resistance to representationalism opens onto questions about the aesthetics and politics of difference, the mechanisms of extraction in neoliberal regimes, and the limitations of agency as a critical model. Ultimately, it is only with a more radical, mutable, and porous model of core concepts like representation and abstraction that we can sense how critical practice might be able to mobilize the singular affects, inertias, and potentialities of art in a moment when its most fundamental reasons for being have undergone profound transformation and can no longer be taken for granted.

*

Since the early 2010s, one long-overdue and overwhelmingly necessary development of US art discourse has been the emergence of a rigorous and relatively broad-based investment in the history of modern and contemporary Black art. During this period, prominent museums have displayed major touring exhibitions like “We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85” (Brooklyn Museum, New York, 2017), “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power” (Tate Modern, London, 2017), and “The Freedom Principle: Experiments in Art and Music, 1965 to Now” (ICA Philadelphia, 2016–17); while university presses have published high-profile art historical studies by scholars including Kellie Jones, Huey Copeland, Krista Thompson, and Darby English.4

It could be the case that this surge reflects the genuine (if belated) transformation of diversifying (but still liberal and majority-white) institutions in the wake of #BlackLivesMatter; it could of course just as easily be that these actions were primarily intended to pre-empt conflicts like those that beset the Whitney Museum during its 2017 Biennial, or those which have dogged other parts of the culture industry, like #OscarsSoWhite. Whatever the reason, this exceptional production of knowledge indisputably represents a watershed moment, bringing huge amounts of previously marginalized Black art to wider audiences while beginning to dismantle received ideas that have long constricted its critical reception.

Among these, one of the most entrenched is an idea that dates back to the era of the Black Arts Movement (and is sometimes reductively attributed to Amiri Baraka): namely, that for a Black artist to make abstract, experimental, or overly “aestheticized” work is to abandon her role within collective liberation struggle, and that effective revolutionary art must be representational in a dual sense, using figurative means to serve the interests of a broad popular audience. While this position––a prime example of representationalism in its most militant, commandment-like guise––may have served a useful purpose in that moment, it was by no means universally adopted then, and was moreover out of step with the ways in which committed artists would actually go on to practice through the 1970s and beyond.

This discrepancy was clear to see in a recent MoMA exhibition documenting the history of Just Above Midtown, the legendary but long overlooked Black-run alternative space that occupied several Manhattan locations between 1974 and 1986. The show, curated by Thomas Jean Lax and Lilia Rocio Taboada in collaboration with JAM founding director Linda Goode Bryant, marked one of the few instances to date in which MoMA has openly acknowledged the pivotal role of the many grassroots counter-institutions that have sought to contest the hegemony of the major collecting museums (most prominently itself) that have historically defined New York’s cultural landscape. It further departed from precedent in its relatively modest appearance, presenting itself unashamedly as a thoughtful and demanding intervention, disproportionately based around gallery archives, exhibition and performance documentation, and a body of newly commissioned interviews.

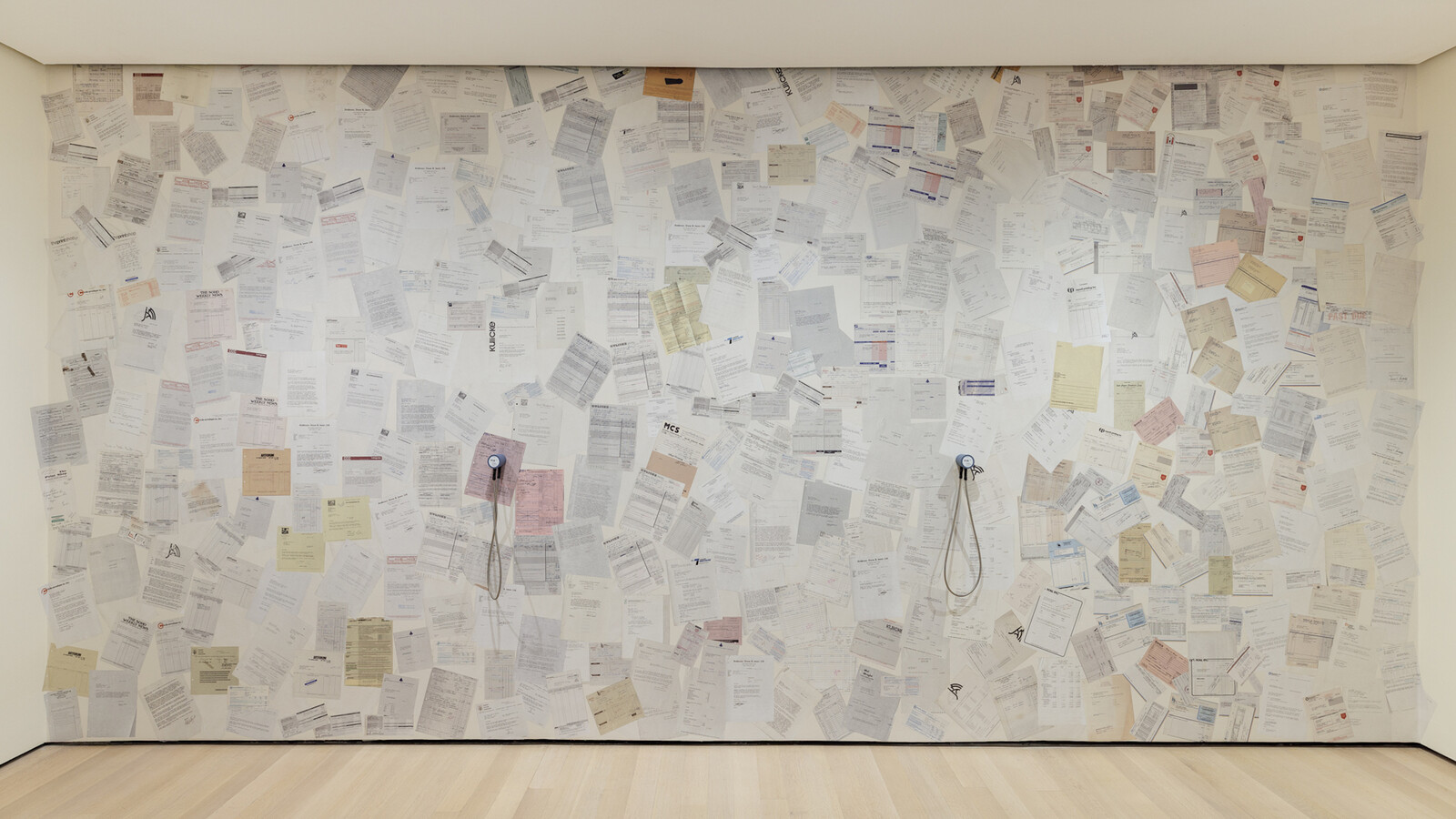

For those who are too young to have ever visited JAM, one of the show’s revelations was its chorus of testimonials to the admirable determination of the space’s principals, especially Goode Bryant––a commitment that was deeply personal, aesthetic, and political, and that was indelibly symbolized by a room whose walls were literally papered over by the hundreds of collection notices JAM received during the years in which its operating costs were covered by Goode Bryant’s own overdrawn credit cards. As became clear, the ultimate goal of this project was not to find better ways to commodify work by Black artists––or to help individual artists develop the sort of work that could ultimately be shown in venues like MoMA––but rather to ground aesthetic experimentation in forms of collective social life with clear links to Black liberation struggles.

Here, representation wasn’t primarily conceived as an artistic convention, or even as a question of financial relationships (i.e. between an artist and a commercial gallery). Rather, it became closely entwined with the question of collective self-determination. To launch a Black-owned and -operated space was to appropriate a central mediating element of cultural production in a way that broke radically with the prevailing conventions of liberal bourgeois politics. As Goode Bryant recollects, what she and the other JAM principals desired was not to integrate existing white (and typically more or less openly white supremacist) institutions; it was rather to pursue an autonomous path centered around desegregation, mapping out “a total, complete world and idea unto itself.”5

A crucial aspect of this radical world-building was to rearticulate the aesthetics and politics of Black art in a moment when the intense mobilization of the 1960s had given way to disillusionment and entrenchment. As Goode Bryant recalls, the landscape of the early 1970s was organized around rigid regional and stylistic rivalries, in which most newly founded alternative spaces were devoted to showing stylistically predictable nationalist work (what she refers to, not unkindly, as “Black-women-nursing-babies art”). JAM refused these reified positions from the start by openly aligning itself with models of artmaking that were forcefully and unapologetically Black, but that adopted the critical and commercial risks associated with emergent forms of experimental intermedia art, exploring links between postminimal sculpture, conceptualism, and performance. Underlying these seemingly disparate practices was a consistent, determined rejection of received ideas about how abstraction and representation should operate.

One prominent exemplar of this approach––and one who has only recently begun to receive the attention her career undeniably deserves––is Senga Nengudi, who showed sculptural installations and collaborative performances at JAM on numerous occasions. A key point of departure for much of Nengudi’s work is its appropriation of pantyhose: a material that has quietly obsolesced over the past several generations, but which in the 1970s and ’80s was ubiquitous and unmistakably coded with patriarchal and racialized values as a lure for the male gaze, marketed with terms like “nude” and “skin.” The genius of Nengudi’s sculptures lies in their ability to effect a kind of double movement: first, they represent hosiery as an ideologically active site, where mundane materials and experiences are invested with abstract, exploitative assumptions about blackness and femininity; then, they proceed to disable, reprogram, and ridicule that function. Sometimes this occurs by shearing and stretching the hose into odd geometric formations; at others, by overloading it with sand until it droops into misshapen, pendulous globules that are somehow at once fascinating, embarrassing, and hilarious.

Another figure whose early career intersected with JAM in fascinating and little-known ways is David Hammons. By the time JAM opened, Hammons had already attracted considerable recognition for his body prints, which closely resembled Nengudi’s pantyhose sculptures in their acute focus on bodily surfaces as a site at which the repressive abstract mechanisms of ideology become sensible through different forms of representation. When Goode Bryant invited Hammons to show at JAM in 1975, both she and the audience expected he would be showing body prints or similar work. Instead, Hammons informed the gallery shortly before the opening that he would be exhibiting only recent work: “paintings” made by staining paper bags with cooking oil and pork grease, and readymade “sculptures” combining wire armatures with Black hair.

Not surprisingly the show, irreverently entitled “Greasy Bags & Barbeque Bones,” quickly went off the rails. Goode Bryant had commissioned an intermediary text by the Met curator Lowery Stokes Sims, which compared the stains from pork ribs to modernist Color Field paintings (an association that the artist seems to have intended, although presumably with more satirical effect), but Hammons demanded that the essay be eliminated so his work could speak for itself. An overflowing crowd packed the space; dividing themselves into pro-abstraction and pro-figuration “tribes,” the two groups heatedly discussed the new work, and both concluded that they hated it. As Goode Bryant recently recalled, members of each group confronted Hammons, angrily asking him, “What the fuck is this shit, man?”6

At that point, things took an even more unexpected turn. Goode Bryant spoke up to ask everyone to calm themselves and sit down so that there could be an open and productive conversation about the work. One of the first people to speak argued that work made from pig bones and Black hair couldn’t be art, but after a moment someone else asked why exactly it couldn’t. Gradually more members of the audience came around to the latter view, enacting precisely the sort of change in opinion that enabled JAM to persuade an increasing share of its audience that Black art could be just as experimental as the work validated by white institutions, and that it could be so without compromising its politics. It remains unknown what role Hammons played in the discussion or what he might have thought about it, but he clearly saw the need to connect more directly with his audience, subsequently leading a “Print-In” at the gallery during which visitors could make their own body prints to serve as gifts for family members who couldn’t otherwise have afforded to buy art.

This episode was part of a central transformation in Hammons’s practice, in which he would shift his focus from printmaking to conceptually informed, appropriation-based sculptures that simultaneously revealed and reworked the mechanisms through which sensible forms were overwritten by racialized coding, whether in materials like grease and hair or in objects like basketballs, liquor bottles, and hoodies. While this history is gradually becoming common knowledge, it is typically framed as the achievement of a singular artist, rather than as the product of an intensely generative and collaborative world such as the one that JAM enabled. As the MoMA exhibition showed, Hammons was an important part of JAM’s radical world-making project, collaborating and sharing affinities with figures including Randy Williams and Howardena Pindell, as well as Nengudi. These overlaps were not only facilitated by Goode Bryant; they were theorized, under the heading of “contextures,” a term/concept that gave its name to a 1978 book, as well as to a series of subsequent exhibitions.7

The critical force of this concept is plainly evident in its neologistic form: contexture is a hybrid, aesthetic-political quality in which we can simultaneously perceive the quasi-autonomous sensate dimensions of an artwork and its embedment within a determinate social conjuncture. Within such a framework it makes no sense to argue that either abstraction or representation could somehow make for better art and/or politics––whether or not these two practices or the material forms they generate are in fact separable from each other, they both remain inextricably bound up within the same extra-artistic conditions.

This subtle, rigorous, and productive line of thinking clearly informed Just Above Midtown, both in its still-overlooked run as an independent space and in its incongruous but nevertheless compelling reincarnation at MoMA. If there is one work from the show that best encapsulates the art of contexture, it is arguably Randy Williams’s brilliant and altogether forgotten L’art abstrait (1977), a construction combining material remnants of working-class urban life (pallets, lottery tickets) with French modernist art history textbooks. It is hard to imagine a more shrewd and cutting demonstration that abstraction is not, has never been, and can never be universal in the ways that its (Western, liberal, bourgeois, and often white supremacist) ostensible champions have claimed.

The fact that Williams’s piece could hit so hard nearly fifty years later speaks not only to its prescience or to the stubborn inertia of the ideology it opposed, but also to the critical force unlocked by the contextural models developed by Linda Goode Bryant and the other members of the JAM circle. As the second part of this text will argue, the power of this approach is such that it not only demands new attention nearly a half century after its inception; it can also serve as a framework for unpacking the formal and theoretical questions that are at stake in some of the most compelling and vital practices currently being elaborated today under vastly different conditions.

I would like to thank Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa and J. Myers-Szupinska for their valuable assistance.

Read the second part of the essay here.

Jed Perl, “Between Abstraction and Representation,” The New York Review of Books (November 24, 2022), https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2022/11/24/between-abstraction-and-representation-jed-perl/.

The most influential contributions to the critical debates surrounding this history include Eva Cockroft, “Abstract Expressionism, Weapon of the Cold War,” Artforum, vol. 12, no. 10 (Summer 1974), and Frances Stonor Saunders, The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters (New York: The New Press, 2001).

For a philosophical critique of representation, see Jacques Derrida, “Sending: On Representation,” trans. Peter Caws and Mary Ann Caws, Social Research, vol. 49, no. 2 (Summer 1982); for a critical overview of poststructuralist representation theory see Stuart Hall, “The Work of Representation,” in Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices, ed. Stuart Hall (London: Open University, 1997).

See for example Kellie Jones, South of Pico: African American Artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017); Huey Copeland, Bound to Appear: Art, Slavery, and the Site of Blackness in Multicultural America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013); Krista Thompson, Shine: The Visual Economy of Light in African Diasporic Aesthetic Practice (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015); and Darby English, To Describe a Life: Notes From the Intersection of Race and Terror (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019).

This reference and those below are drawn from “Can JAM Be JAM at MoMA? A Conversation between Linda Goode Bryant and Thelma Golden,” in Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces, eds. Thomas Jean Lax and Lilia Rocio Taboada (New York: MoMA, 2021), 13–19.

Ibid.

See Just Above Midtown, 40-44.