London’s galleries are open again. Exhibitions that were paused or postponed last fall have emerged from enforced hibernation into a cultural environment altered by six months of—well, not very much. To a quarantine-addled critic, this presents a quandary. One of the pleasures—and pitfalls—of writing about art is using it as a measure of lived experience: of holding work up to the light and saying, ah yes, this reminds me of something. The problem is, I haven’t much new experience against which to gauge the work. But maybe I’m not alone. In the capital’s galleries I kept noticing pieces, many made over this past year, that described a version of the same space—an unstable interior, variously possessed and infiltrated by outside forces. Which is to say, a state of mind. Or was I just projecting?

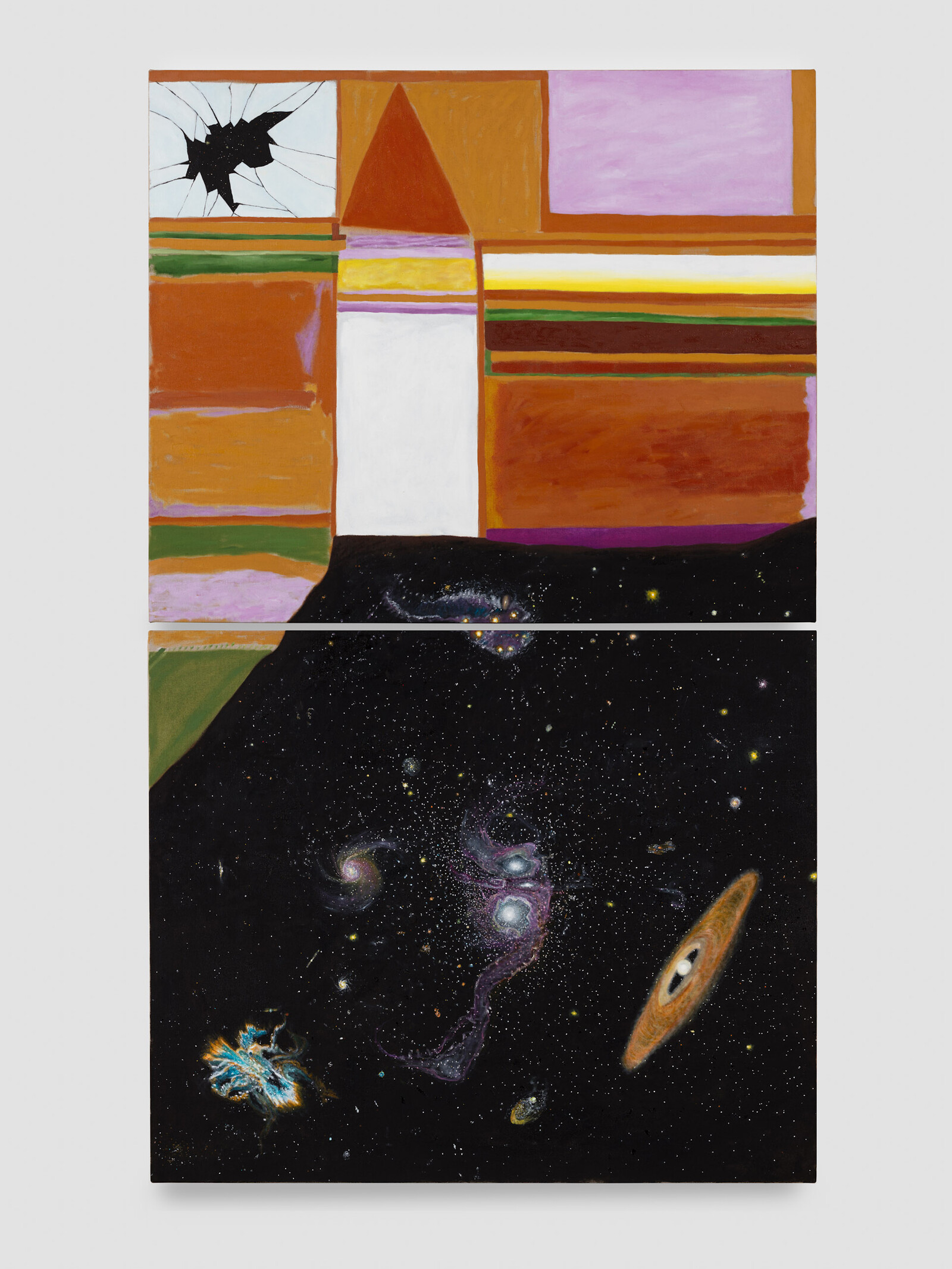

Leidy Churchman’s “The Between is Ringing,” at Rodeo’s Bourdon Street space, is a small, rewarding show of a dozen new paintings that range from smudgy abstraction to cartoonish exuberance. The work subtitled Diptych (all works share a main title with the exhibition and are dated 2020) comprises two oil-on-linen paintings, stacked one atop the other, depicting an abstracted living room that is also an existential void. The walls of this interior, which occupy the upper and left portions of the picture plane, are assembled from soft, Rothko-esque panels of ochre, tangerine, and candy-floss pink inset with bars of moss-green, flax-yellow, and white. Yet where the floor should be is a pictorial trap-door. It opens onto fathomless outer space, nebulae adrift in the twinkling void. A smashed window in the upper left corner suggests that this intrusion of cosmic scale into a domestic setting may be a violent one, but to someone trapped the same image would signal escape. Churchman’s intent may be to suggest that the difference is one of perception.

A practicing Buddhist, the artist’s works are here shaped by an interest in dependent origination. One interpretation of this principle states that everything has a cause and an effect, from a mark on a canvas to a mutation in a strand of RNA; since nothing is exempt from this rule, everything is connected in a vast web of interdependent causality. Given the events of the past year, this show’s underlying theme feels less like a spiritual hypothesis than common sense. To see the cosmos under the carpet is to understand that no interior, be it bodily, architectural, or psychological, can be separated from its universal context. Or, to put it more bluntly: there is no interior.

Round the corner from Rodeo is Rachel Whiteread’s “Internal Objects,” at Gagosian’s Grovesnor Hill space. Central to this otherwise low-wattage solo show are a pair of fragile, broken sculptures. Built from salvaged scrap painted a uniform white, the works resemble derelict huts half-demolished by natural forces, the roofs caved in, fallen branches making chicken wire sag, the lids of tin cans stuck like barnacles to the outer walls. Inspired by the American wilderness and made during lockdown, the sledgehammer directness of the works’ titles, Poltergeist (2020) and Doppelgänger (2020–21), contrasts with their material frailty. The sculptures made me feel uneasy, but for reasons other than intended: hard to ignore the reek of gentrification when a ruined dwelling is transformed into a commodity by being brought within the walls of a gallery and beautified with a lick of paint (whitewashed?). The works stood in ironic counterpoint to Whiteread’s House, commissioned by the publicly funded arts organization Artangel: a concrete cast of the inside of a terraced dwelling, which stood exposed to the elements in London’s Mile End for 11 weeks during the winter of 1993 to ’94, at the end of which it was demolished. For a commercial gallery to function it must create spaces of exclusivity, establish barriers to defend against the invasive threat of, if not cosmic interdependence, then at least theft and vandalism. Insecure interiors had begun to seem like a motif of London’s current exhibitions—indeed, of the city itself.

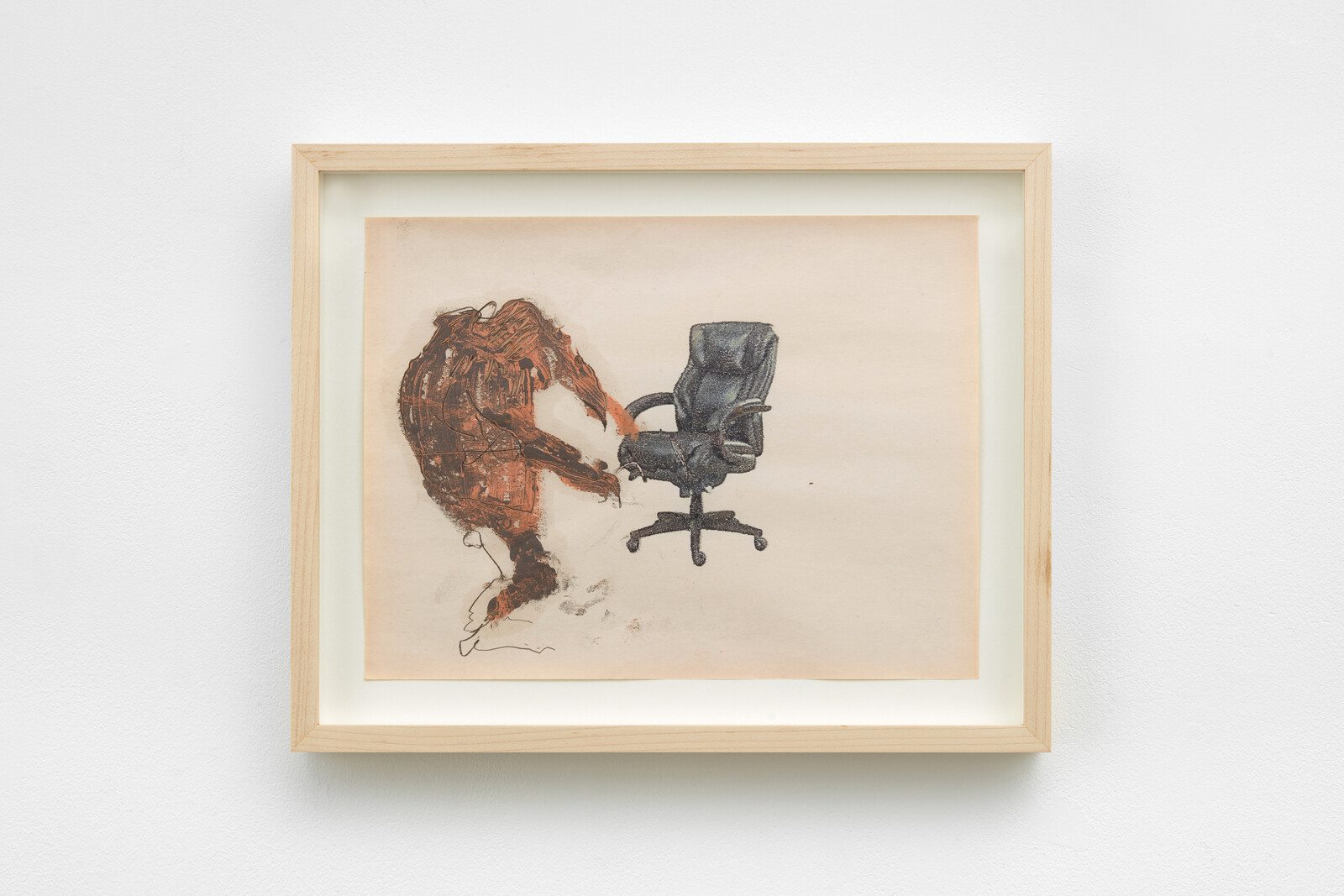

Buildings had emptied out. I passed dusty shop-fronts with Notices of Forfeiture in the windows. Soho’s pubs and restaurants had spilled onto the pavements, the tables crowded. Seeing people socialising outdoors was a reminder of how much of the previous months has been spent not doing that: if you weren’t protesting, you were stewing. Uri Aran’s “Oranges vs Them,” a one-room micro-show at Sadie Coles HQ’s Kingly Street outpost, comprises eight works on paper that read like attempts to form new visual languages while bouncing off the walls, pencil and pastel in hand. In Make Like (2021), a tangerine blur resembling a hunched gargoyle stalks towards an office chair. Working from home for months on end does something to a psyche: I identified with the scratchy timbre of Aran’s work. I felt more than my usual low tolerance of—indeed, a degree of affection for—brattishness here, too. Notes (2020) features no less than four doodled penises. Frustration can be funny, and humor, one hopes, brings some measure of relief.

Aran’s impishness contrasted, across town at Modern Art’s Helmet Row outpost, with Elene Chantladze’s misty, dreamlike works on scraps of discarded paper and card, which the artist colored using domestically available materials such as mulberry juice, beets, and cinders, alongside pencil and paint. Growing up on the Black Sea coast of what is now Georgia in the years after World War Two, she learned to paint using her fingers and matchsticks. Comprising new and earlier works (the earliest dates from 1992) displayed on a low shelf running around the edge of the gallery, the works in her first UK exhibition are miniature worlds of subjectivity, in which fictional characters and animals blur in humid rooms and abstract, gaseous clouds of overlapping limbs.

These works differ in many ways from Churchman’s; what they share is a compelling ambivalence. It’s partly a question of style—Chantladze’s expressive marks encompass scratches, splodges, and smears via which figures and surroundings dissolve—and of juxtaposed registers. In Red riding hood (2017) the eponymous figure, here resembling a rag doll, lies tumbled in a marsh. She has a sky-blue skirt and googly eyes, but her head is on fire, flames erupting to the left of the image, black smoke billowing above. While the artist’s imagery is fanciful at first glance, reminiscent of greetings cards or illustrations in children’s books, she also reckons with the darkest periods of her home country’s recent history: the Beslan school siege of 2004, for example, and the Russo-Georgian War of 2008. Working with whatever materials were available to her, Chantladze “tried to find a way out of the situation.”1

Walking up the stairs to Sandra Mujinga’s “Spectral Keepers” at the Approach, light was leaking under the gallery door, an acid shade I associate with plutonium, horror films, and UFOs. Four thin, looming figures stood in a room flooded green by radiating strip-lights. The sculptures’ long-limbed frames were wreathed and cinched in gray-toned utility gear from which straps dangled, skeletal legs ghosted by translucent tulle. Their heads—modelled on the hoods worn by medieval beekeepers—were faceless, eyeless, mutely staring down. At the feet of each was a cone-shaped basket. Mujinga’s work draws on Afrofuturist writers such as Octavia E. Butler and N. K. Jemisin, and it felt deliberately ambiguous whether these characters are warriors, oracles, or farmers, and from a climate-ravaged planet, a posthuman future, or both. Their cloaks may be religious robes or camouflage, an adaptive response to a world—a hostile glare—that left them dangerously exposed. The screens used as special effects backdrops in movies are green because the shade doesn’t match any natural skin tone or hair color. Far less hospitable, then, had the all-pervasive color been white.

I blinked. Wasn’t this installation saturated with green? Looking up, I saw that the fluorescent bulbs had changed to white; peering through the window, the street looked its normal shade. I wondered if the lights had been set to fade in and out on a timer. But when I held up my phone to take a photo the screen pulsed rhythmically, as though the green fluorescence was jamming the signal. That I hadn’t noticed my eyes adapting to these conditions felt integral to the work: a color had become invisible to me by dint of its universality.

To expose the ease with which vision can be altered, transforming the experience of a room, the beings in it, and one’s view of the world beyond, is not to deny that appearances have deeply entrenched and often violent real-world effects; rather, it is to suggest that all perception is mediation. The interior, in this case, was not a physical space but my subjective apprehension of the world. Mujinga’s exhibition—the installation of which the artist directed over FaceTime during lockdown—felt all the more powerful for being so pared-back, focused as much on perceptual transformation as on objects. I emerged into London blinking again. It took a moment for my eyes to adjust.

“Interview with Elene Chantladze,” Modern Art (2021), https://vimeo.com/499567911.