There’s a moment towards the end of Jumana Manna’s film Foragers (2022), in her show of the same name at Hollybush Gardens, that stuck with me through Frieze week. After an hour spent following Palestinian foragers searching for a plant the Israeli authorities have deemed illegal to pick, the viewer is plunged into darkness shot through with brief glimpses of rusted orange-red semicircles. Slowly, the image resolves into low foliage illuminated fleetingly by a patrol car’s rotating beacon lights. This momentary break from reality—from documentary-style footage towards something resembling abstract animation—resonated with a wider disorientation I felt across some three-dozen exhibitions and an art fair. I don’t know if you can call it a theme, a trend, or a vibe, but it is perhaps best described as a sense of unease.

Such unease seems to prompt the creation of shelters or safe-spaces in works as disparate as the dark cork-lined walls of William Kentridge’s retrospective at the Royal Academy and Olukemi Lijadu’s cloth-lined viewing room for her film Guardian Angel (2022) at V.O Curations. When time is jumbled or out of joint, art can be a means to step ever so slightly back, to gain perspective, and to reimagine a disorienting present.

The same impulse might also lie behind the present wave of figuration: amidst the maelstrom, attempts to pin the world for a brief time. Simeon Barclay’s “In the Name of the Father,” at South London Gallery, is one of a number of exhibitions to remix and reinhabit figures of the past. It riffs on other artists: Beuysian felt suits with Mike Kelley-like trails of plush toys running out from their pant legs, Brancusi-style stacks of blue plastic barrels, Lutz Bacher-esque use of a Darth Vader cardboard cutout. Iceberg (2022) is a column with a hutch with its door hanging expectantly open, atop which sits a yellow Perspex box and a small, wooden doghouse. Trapped in the Perspex is a puppet: a carved self-portrait of the artist in a Donald Duck outfit. This tragicomic figure, caught somewhere between escape and domestication, faces off with another puppet named Walls in the Head (2022). This man with a bruised face is meant to be a character from the film Scum (1979)⎯ it looks to me like a young, street-fighting Gilles Deleuze.

The room is bisected by Higher Purchase (2022), a line of eight nondescript closed doors each with a small blue sign. “BRIGHT INFERIORITY BRINK / MUTE RUIN” reads one, like the office of some inscrutable purgatorial bureaucracy. All the doors I try are locked. “GRIT LOCAL GUARD / INSTITUTE LOST WAITING VISIBLE” is the only one that eventually opens. Though there’s no particular insight or reward: sure, there’s the base of a few of the works that you saw peeking over the partition, and two fairly generic geometric canvases, but all I really get is being on the other side of the doors. You can try killing your idols to escape the past but, Barclay suggests, it doesn’t lead anywhere.

Zadie Xa’s installation “House Gods, Animal Guides and Five Ways 2 Forgiveness” at Whitechapel Gallery is similarly oneiric, a dream state that feeds instead on the instruction of tradition and myth. Drawing on Korean shamanistic practices and ritual trappings, “House Gods” feels funereal without the mourning; a send-off for an old way of life. At the center of the room is a wooden hut, the interior of which is lined with a surreal landscape painting. On its roof occupied by a parade of small chimerical sculptural figures, described by the wall panels as “funerary figurines” to accompany the deceased into the afterlife: The Musician (2022) holds a small drum, poised ready to strike, its face covered by a dolphin mask; The Acrobat (2022) balances on the roof’s edge by its hands, its fox-masked face staring at you defiantly as its eight tails fan out behind it. The robe 4 the Women of lodo (2022) hangs from the ceiling, its folds a patchwork of vibrant green and a shiny silver fabric, its lining a wash of bright pinks and blues, two cloth flowers decorating its front. Covering the stylish robe is a motif of knives, each blade made from reflective material. The hanging robes here are “guides,” more in the sense of instruction than following: not leading us elsewhere, but setting out proto-magical tools for cutting through time, to lead ourselves to alternative presents.

Any art fair is a hyper-example of overlapping and competing timelines. Most of those at this year’s Frieze London seemed happy to sit back on serene and conservative creative gestures—nostalgia, after all, is another response to disorientation. Yet amidst the expansive canvases and rainbow colors were other reconfigurations of what the past might be. Strewn across the floor of the Tina Kim Gallery booth is what looks like the carcass of some unknown creature the size and shape of a small whale. Mire Lee’s Endless House (2021) is a burrow of uneven bone-like appendages that veer between off white and more dirty greys. It appears alien, an entity with no recognizable anatomy—until you spot the two black plastic ventilation panels embedded in one end, like some hybrid fossil we have yet to accept as part of our ecology, another remnant of a timeline we’ve neglected.

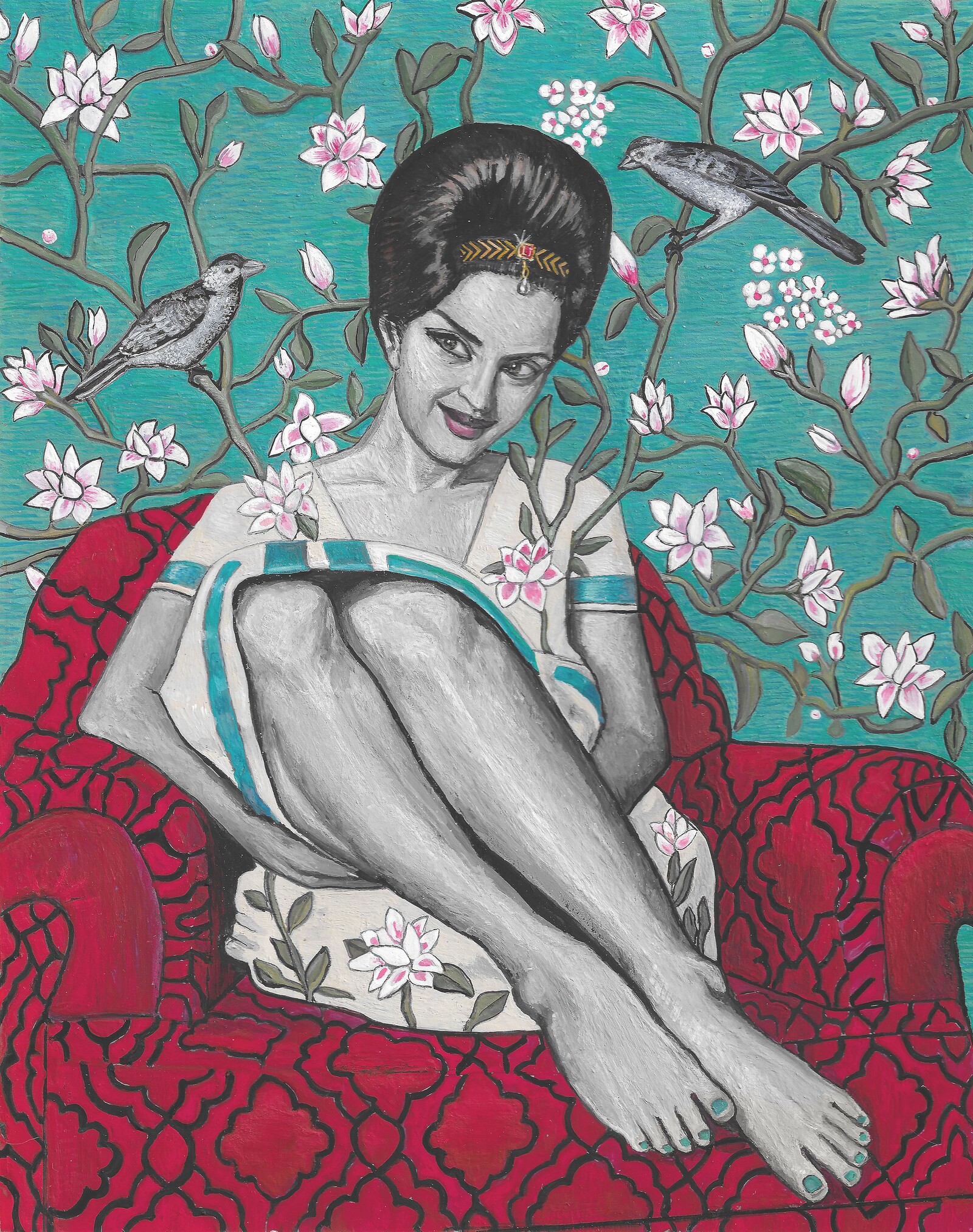

The floor and walls of the Barbican Curve are a deep turquoise, lined with intricately hand-painted geometric patterns. Along the long wall are a set of small, framed portrait drawings of women writers, actors, musicians, directors, and pop stars who shaped the Iranian cultural landscape before the 1979 revolution. In The Woman in the Mirror (Portrait of Fereshteh Jenabi) (2021), one of the works comprising Soheila Sokhanvari’s solo commission “Rebel Rebel,” a woman sits facing away from us on the floor combing her hair; we see her reflection in a mirror. She is colored in grayscale pencil, while the mirror sits on a detailed red carpet, orange floral patterned curtains in the background. A biographical note explains that Jenabi was a groundbreaking actress who was sentenced to death after the revolution and went into hiding for two decades.

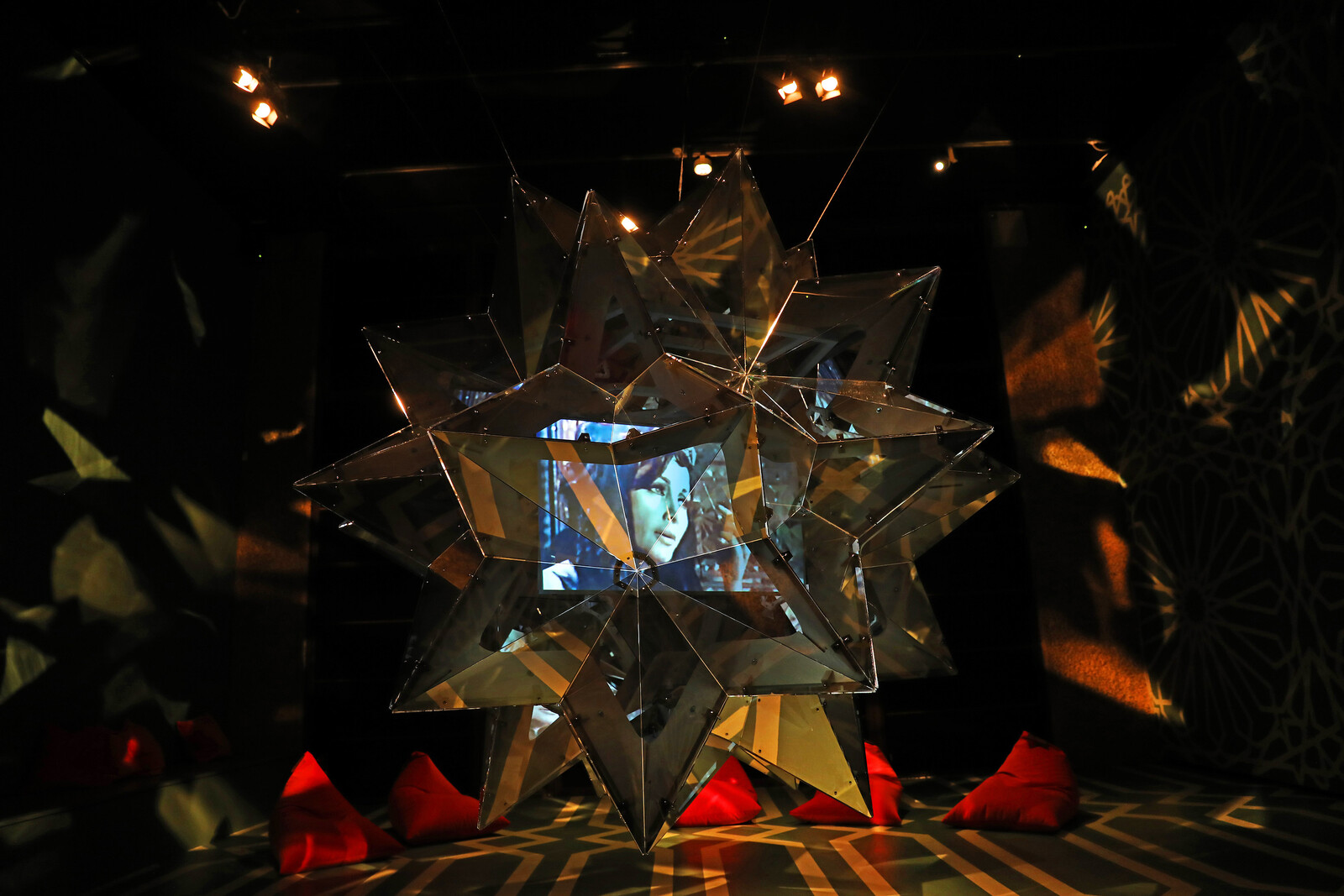

The 27 other portraits in “Rebel Rebel” follow a similar pattern: clear-eyed depictions of formerly successful artists, with biographies that detail their achievements, followed by their choices after 1979⎯to renounce their work, face imprisonment, or leave the country. At the end of the hall is a large, crystalline structure housing a screen, on which a collage of the assembled women’s work plays, their words and music echoing through the space, the art of Iranian woman past refracting onto the protests of Iranian women now. Art is not a haven, Sokhanvari reminds us, or an escape. It is an attempt to still the world for a moment; to apprehend some lost or hallucinated corner of it; and to glimpse the shape of pasts, presents, and futures in the dark.