October 10, 2021–January 9, 2022

“Witch Hunt” opens with an unnerving chill courtesy of El agua del Río Bravo (2021), a sculptural installation by Teresa Margolles that envelops visitors ascending the Hammer’s steps in air cooled by water gathered from the Río Bravo, along the US-Mexican border, by residents of the Casa Respetttrans women’s shelter. The work sets the tone for an exhibition responding to today’s generalized culture of misogyny with powerful work by an international roster of midcareer women artists.

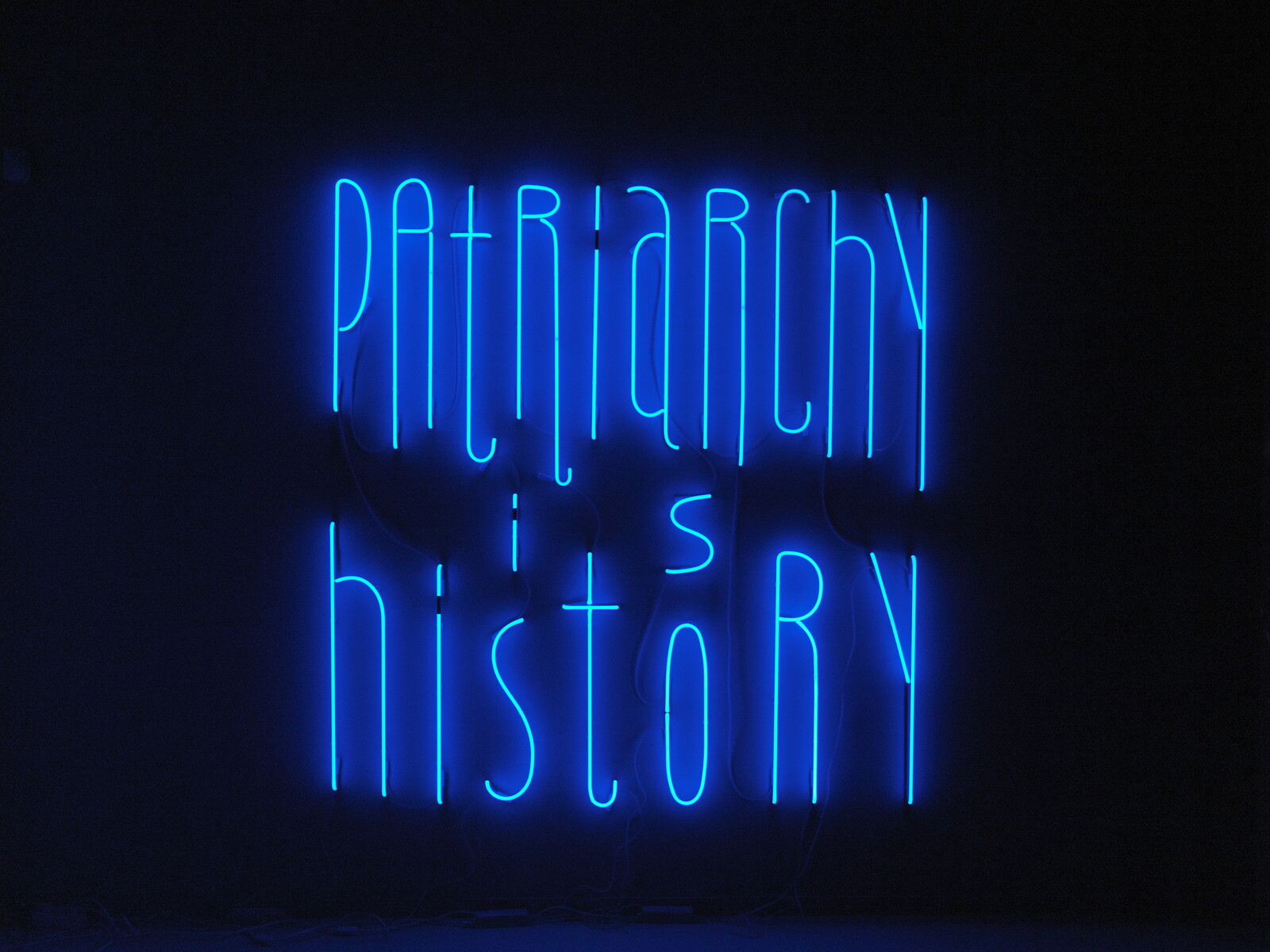

It may be tempting to assume that the show’s title is mere allegory: that concerns about cabals of female devil worship no longer occupy the minds of contemporary Americans. But a cursory review of the news, from Pizzagate to the “lock her up” refrain against Hillary Clinton and death threats against AOC, show that women who threaten to disrupt male power will continue to be accused of evil. And where witch hunts once referred to the persecution of the weak by the powerful, the script flipped in 1973 when Richard Nixon used the term to denounce the Watergate hearings, setting in motion a pattern of powerful men—most notably Donald Trump—claiming to be the subjects of exactly such a threat. This show across two institutions was planned long before last year’s attack on the US Capitol, yet its coincidence with the assault’s anniversary, and the attendant resurgence in rhetoric around what (Nixon-tattooed) Trump strategist Roger Stone has called “witch hunt 3.0,” have shifted the meaning of the term even further.1 Curators Connie Butler, Anne Ellegood, and Nika Chilewich make clear that they use the phrase “witch hunt” to invoke male leaders “threatened with the loss of their status” who appropriate victimhood to serve their own persecution complex.2

Curiously, of the fifteen pieces on view, only two more or less directly relate to that expressed framing of “witch hunt” as the supposed persecution of the powerful. At the ICA, Lara Schnitger’s giantess sculpture Kolossoi (2021) is inspired by a fourth-century clay figure, her body stabbed with spikes, who was found along with a spell calling on the gods: “Drag her by the hair, by the guts, until she no longer scorns me.” Schnitger inverts the original’s incantation to control and dominate by piercing the body with flags that invoke liberation, respect, and female pleasure. Taking a different tack, at the Hammer, Yael Bartana’s Two Minutes to Midnight (2021) taps into the consequences of toxic masculinity with an all-femme Doctor Strangelove video riff on the thought experiment “what if women ruled the world?” The work places actors and real-life experts in a fictional all-female nation’s “peace room” debate about nuclear disarmament in the face of mounting threats from the maniacal “President Twitler,” a thinly veiled reference to the orange menace himself.

From here, the exhibition begins to drift from the curatorial signaling. At the ICA, moving from Every Ocean Hughes’s film about a millennial death doula (One Big Bag, 2021), to Schnitger’s sculptures, to a suite of devotional makeup portraits by Vaginal Davis, a framework of notions around treatment of the body begins to emerge. Minerva Cuevas’s Feast or Famine (2015), a critical rumination on the corporate logic and consequences of chocolate as cash-crop of the American colonies, swerves the narrative in a different direction. Silvia Federici has written powerfully on the history of witch hunts’ connection to capitalism, class struggle, and economies of colonial exploitation, but this idea moves “witch hunt” away from the expression of a male persecution complex towards something far broader.3

At the Hammer, things get murkier, though it’s possible to discern certain connecting threads running through the disparate works. An exploration of craft and a drive to make visible women’s labor unite Leonor Antunes’s the home maker and her domain I, II (2021) and Laura Lima’s Alfaiataria [Tailor Shop] (2014/2021). Shu Lea Cheang’s UKI Virus Rising (2018)—a pulsing video installation of a feminine robot that morphs into a tree, then a machine, and finally a virus amid a projection of blood cell mapping—is connected by little more than its medium to Pauline Boudry/Renate Lorenz’s floor-and-video installation Telepathic Improvisation (2017). Both Bouchra Khalili’s The Tempest Society (2017), which uses theater exercises to consider racism and inequality, and Okwui Okpokwasili’s Poor People’s TV Room (2014/2021) engage with ideas of durational performance and experimental theater. Finally, sex and gender performance roughly link Beverly Semmes’s Feminist Responsibility Project (1993/2021)—painted collages of penthouse centerfolds—and Margolles’s coolers. It’s a strong statement that we enter the exhibition through a blast of air cooled by water through which migrant bodies have passed and perished in pursuit of a better life. But after seeing the rest of the show, the waters turn muddy: the risk of the migrant journey is not exclusively female.

The conceptual wandering may be partially attributable to the museography. While the individual contributions to “Witch Hunt” are compelling, that they are all critical works by women operating in a myriad of feminisms isn’t enough to situate them in conversation. Rather, what feels more like a constellation of mini solo exhibitions makes for a disjointed experience as the viewer moves from one artist’s world to the next. In part, this plurality reflects the intersectional reality of feminism today. But, given that the Hammer’s previous major show of feminist work was “Radical Women” in 2017, this disjointedness may also be the result of the pressures of a quinquennial curatorial opportunity to meet the challenges of our moment on as many thematic and political fronts as possible. We need more shows like “Witch Hunt” to share the scholarly, conceptual, and political burden.

Ellis Kim and Kathryn Watson, “Roger Stone says he invoked 5th Amendment before January 6 committee” (CBS, 17 December 2021), https://www.cbsnews.com/news/roger-stone-says-he-invoked-5th-amendment-before-january-6-committee/.

“Witch Hunt” curatorial statement.

Silvia Federici, “Witches and Class Struggle” (Jacobin, 31 October 2018), https://jacobinmag.com/2018/10/witch-hunt-class-struggle-women-autonomy.