A screen at the entrance to Chto Delat’s first solo exhibition in Athens shows four members of the Russian collective on a Zoom call. Each of them sways, swoons, or sighs along to Maya Kristalinskaya’s interpretation of the 1965 torch song Nezhnost’ [Tenderness] as overlaid script tells the group’s history since its formation in 2003. A wall text states that the ballad was a favorite of Yuri Gagarin, the first man ever to be estranged from the planet, and that this performance was recorded during lockdown. As Kalinskaya mourns an earth left empty by separation from her lover, this short portrait of divided friends introduces the themes of the show: how to resist isolation, what it means to belong, and how to be together.

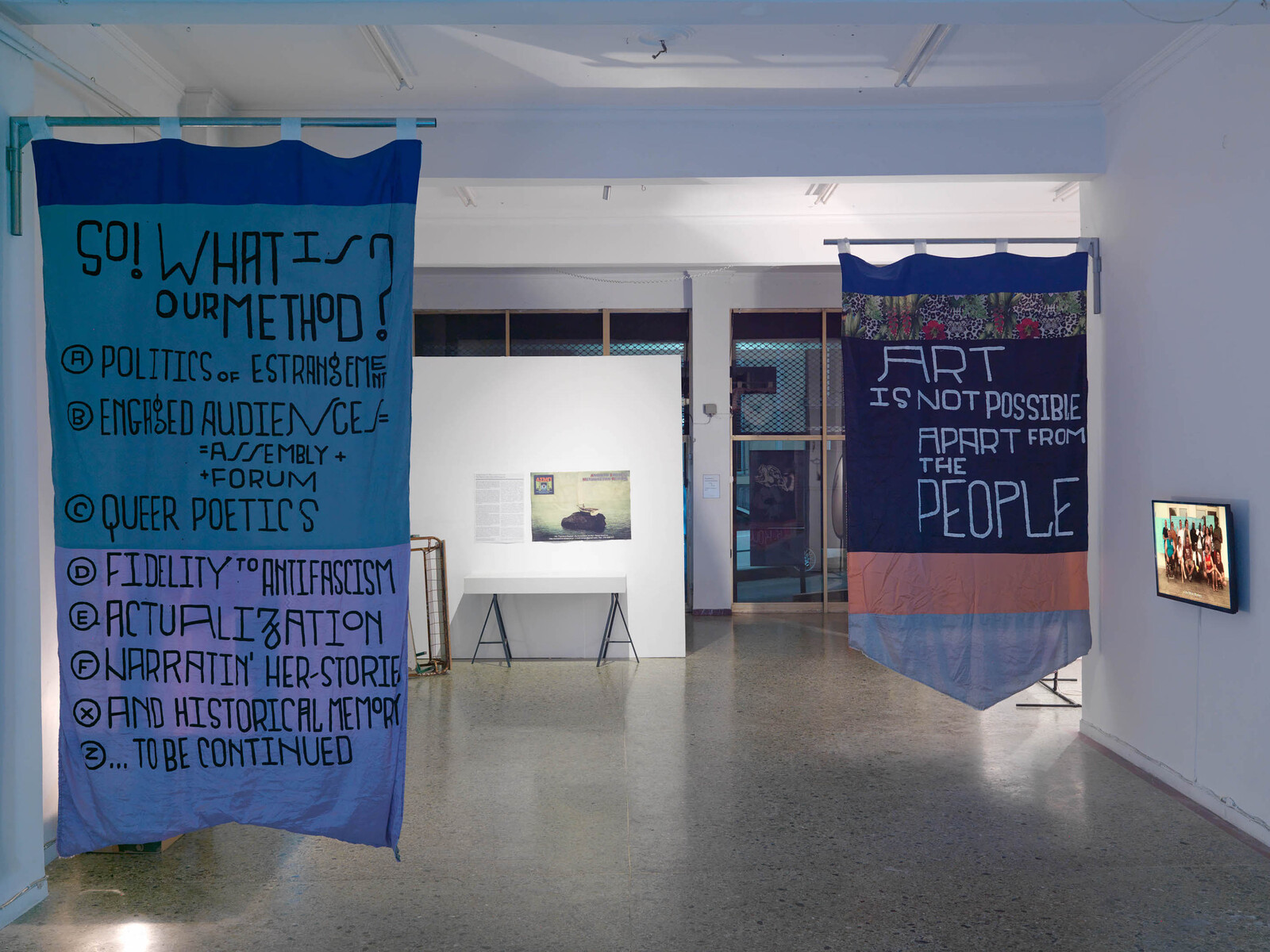

Chto Delat’s interest in these issues predates the pandemic and political crises which have exacerbated them. Filmed in 2011, and exhibited here in a basement screening room, Museum Songspiel: The Netherlands 20xx presents a hypothetical scenario in a near-future that may, a decade ago, have seemed dystopian: a group of asylum seekers have escaped deportation and taken refuge in a modern art museum. A resident artist has the bright idea of dressing them up as performers in the Futurist opera Victory over the Sun (1913), transforming these “criminals” into art and throwing hostile reporters off the scent. It’s an act of good intentions undertaken in bad faith—the disguise smacks of evasion—and establishes the collective’s skepticism of conscience-washing rhetoric about the redemptive power of art. The influence of Aristophanes (namechecked like Brecht in the banners draped around the space) is apparent in the chorus’s biting parabasis: “What a relief! / It turns out that this was just art / Completely harmless!”

In common with the unexpectedly touching Border Musical (2013), which describes a relationship conducted across the cultural divide separating a Russian mining community from its Norwegian neighbor, the film resists the temptation of a simple moral message in favor of staging an ethical dilemma on which the viewer must take a position. This requires interpretative work beyond assigning blame to an othered and supposedly ignorant constituency (in the case of Border Musical, a group of working-class Russian miners) or blithely disavowing systems in which the gallery-going viewer is implicated. When so many western artists are content uncritically to appropriate exoticized or “occult” systems of belief on the vague assumption that they might offer practical ways out of our predicament, these allegories offer a necessary reminder that politically engaged art can be rational, humane, coherent, and intellectually demanding. That these principles might provide a bulwark against the counterfactual and quasi-mystical seductions of fascism is demonstrated by It Has Not Happened to Us Yet. Safe Haven (2016), a two-channel video shown on standing screens at the back of the gallery beneath a line festooned with hand-stitched flags.

The film imagines a scenario in which five dissident artists are granted asylum on a remote Norwegian island. Their stories—told through the performance of butoh-like dances in the landscape—are interspersed with straight and sincere reflections from the islanders on human rights and freedom of speech. The questions raised are directed squarely at the visitor, who is not let off the hook by the kind of dramatic catharsis that salves a conscience: as the pointedly titled It Has Not Happened to Us Yet reflects on the millions who are not protected from persecution by their status as artists, so the artist-migrants in Museum Songspiel are rounded up and deported on the day after their performance.

The construction of alternative systems of education, the promotion of equitable relations, the practice of solidarity, and the expansion of constituencies are instead presented as laborious, time-consuming, and daily activities. People of Flour, Water, and Salt (2016), a “learning-film” shot over the course of several weeks at a temporary autonomous community in Italy, documents this lengthy process. As the residents explore the eminently practical tenets of Zapatismo through participation and play, one striking moment comes when a visiting activist uses a parable to illustrate to an audience including Kurdish and Syrian refugees how community can be built on a collective identity that does not efface individual difference. By testing the truth of the allegory against their own lived experiences, the questioning students enact the principles underpinning it.

Those ideals are put into practice in a new commission, for which Chto Delat collaborated with the Open School for Immigrants in Piraeus. Working with puppeteer Stathis Markopoulos, the students developed a shadow play responding to a “slow study” of Zapatismo, snippets of which are shown alongside interviews in a short video (About the footprints, what we hide in our pockets and other shadows of hope, 2020) complemented in the space by props including a marionette dog and articulated figures behind a lit screen. The absence of the play itself only reinforces that the work is the process, and its end is not an object or authoritative document but to help traumatized people to live.

That this exhibition itself requires time and work—the videos totaling several hours, the wall texts lengthy, the installation sparse and unspectacular—is commensurate with the collective’s antipathy to escapism. In the tradition of satirical and epic theatre, Chto Delat are instead committed to an art that changes how individuals understand their relation to the world, and by extension how they act within it. To do this it must speak directly to its audience: when an especially stupid poet declares in Aristophanes’s The Birds (414 BCE) that the best poems “are those that flap their wings in empty space and are clothed in mist and dense obscurity,” he is thrown out of the revolutionary community with great dispatch. Another of the playwright’s regular targets was the populist tyrant Hyperbolus, who was deposed from power and ostracized to an island where, according to Theopompus, he was forced into a wineskin and hurled into the sea. Like Chto Delat’s, these are ideas that warrant wider application.