David Hammons has long been playing a cat-and-mouse game with the so-called art world. While his professed admiration for Marcel Duchamp appears to have brought him a clear sense of the symbolic and transformational power that contexts confer to objects, it has offered an even sharper awareness of how the mythographic, star-making mechanics of the art world can be used in his favor. The ongoing mythography that has defined the latter part of Hammons’s career—his no-shows at his own openings, his reluctance to engage with critics and the press, his refusal to comment publicly on an “unauthorized” retrospective at Harlem gallery Triple Candie in 2006, thereby leaving open the possibility that the exhibition was his idea—now arrives in one of Lisbon’s most interesting venues, Lumiar Cité, which serves as a platform to promote yet another chapter of this story.

At the heart of “Ted Joans: Exquisite Corpse” is a peculiar version of the famous Surrealist game that poet, musician, and artist Ted Joans initiated in 1976 and which ended in 2005, two years after his death. As the title suggests, Joans conceived Long Distance Exquisite Corpse as a travelling exquisite corpse that would find its 132 invited contributors in different settings and distant geographies. The result is a more than 30-foot-long chain of drawings and collages on the type of perforated paper used by dot matrix printers in the mid-1970s, presented here in a blue vitrine that extends diagonally across the width of Lumiar Cité’s first floor. The graphic approaches vary from abstract doodles to fragments of poetry and cartoonish figures. Reigning among them, as one would expect, are contributions that reflect the interests, signs, and methods of Surrealism.

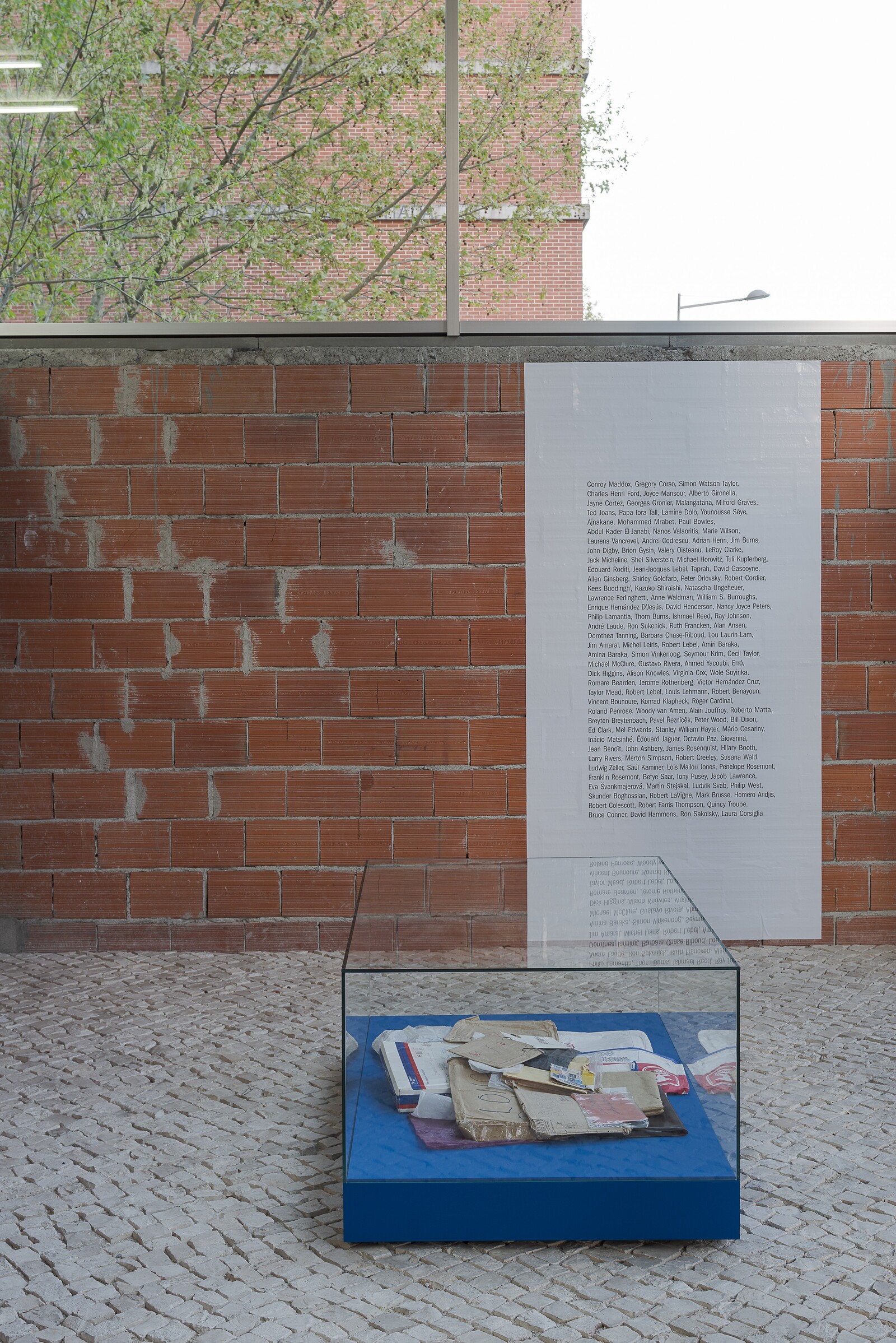

Joans used to say that jazz was his religion and Surrealism his point of view. Contrary to what often happens, he meant what he said and lived what he preached. It is, therefore, only natural that this exquisite corpse has the feel of a jam session including celebrated artists and writers (such as Bruce Conner, Allen Ginsberg, and Dorothea Tanning) side by side with others largely unknown to international audiences; contributors who, like Joans, were part of the artistic milieu of New York along with those who made their careers outside of major cities, in Africa, Mexico, or Portugal. (Portuguese artist Mário Cesariny is among the participants, whose names are listed on a wall text displayed beside another vitrine containing the envelopes and plastic bags in which the exquisite corpse traveled [The Skins of Long Distance Exquisite Corpse, 1976–2005].) All of the contributors were given equal amounts of paper and the same set of conditions, helping to construct a shared ground of elective affinities that Joans dubbed the territory of “dreamers.”

Granted, there is no such thing as a failed exquisite corpse. As the dérive machine that it is, the Surrealist game functions as a kind of reverse iconographer: the more disparate its contents, the more exemplary the set, relative to its objective of stimulating the viewers’ creative imagination in the interval between two (or more) apparently irreconcilable images. Joans knew that the question of content was marginal to his project. Everything played out in the choice of the participants and construction of a community that not only shared aesthetic, ethical, and even political beliefs about art, but above all knew how to take their respective places in a structure in which circumstances, hierarchies, positions, and egos were levelled.

It is precisely this levelling that Hammons destroys by paying “homage” to Joans with an exhibition that takes his name. To justify this generosity, the exhibition includes Hammons’s video Ted Joans: Exquisite Corpse (2001–18), in which Joans is seen opening the exquisite corpse for the first time, in 2001. While Joans engages all his enthusiasm in building an astonishing, first-person account of contemporary Surrealists and their endeavors in the late twentieth century, Hammons makes fleeting, dilettante appearances onscreen, sitting at a desk drawing his own contribution to the exquisite corpse. To top it off, he installed the video screen at a height of nine feet that is not only uncomfortable for viewers, but symptomatic of the subtle but no less deliberate choice to put them in the position of worshippers and his piece (rather than Joans’s project) in the place of the revered thing. That Hammons would choose not to bring to Lisbon a glimpse of his highly relevant work seems only consistent with the options he has taken in recent years. That he would chose to reduce a gesture of generosity, sharing, and artistic commitment to a form of self-indulgence masquerading as a tribute, trying to force viewers into an uncritical compliance while at it, is only sad.