Emma Kunz never called herself an artist. Whether she designated herself in any way is unknown, but her principal activity was research and healing using a pendulum and natural remedies, a practice in which drawings played an integral part. A solo exhibition at Muzeum Susch presents more than 60 of these untitled and undated works, produced from 1938 until her death in ’63. Created in collaboration with London’s Serpentine Gallery, where a show of Kunz’s drawings ended in May, this exhibition features a different selection of works and also a different setting. The museum has softer edges than many: built on the site of a twelfth-century monastery in the Engadin region of Switzerland, with galleries burrowing into the rock, the institutional setting establishes that Kunz’s images can speak on their own terms as art.

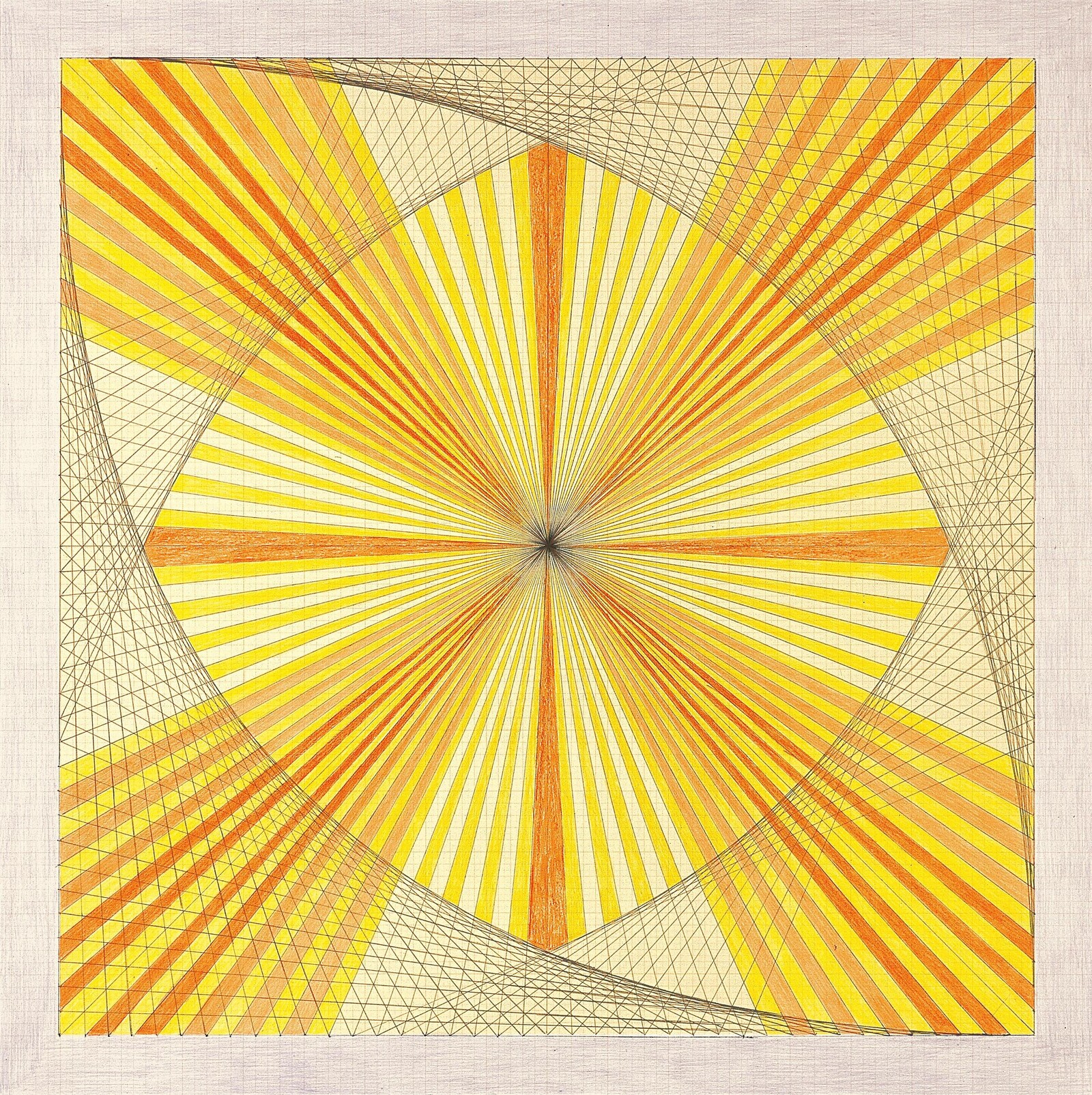

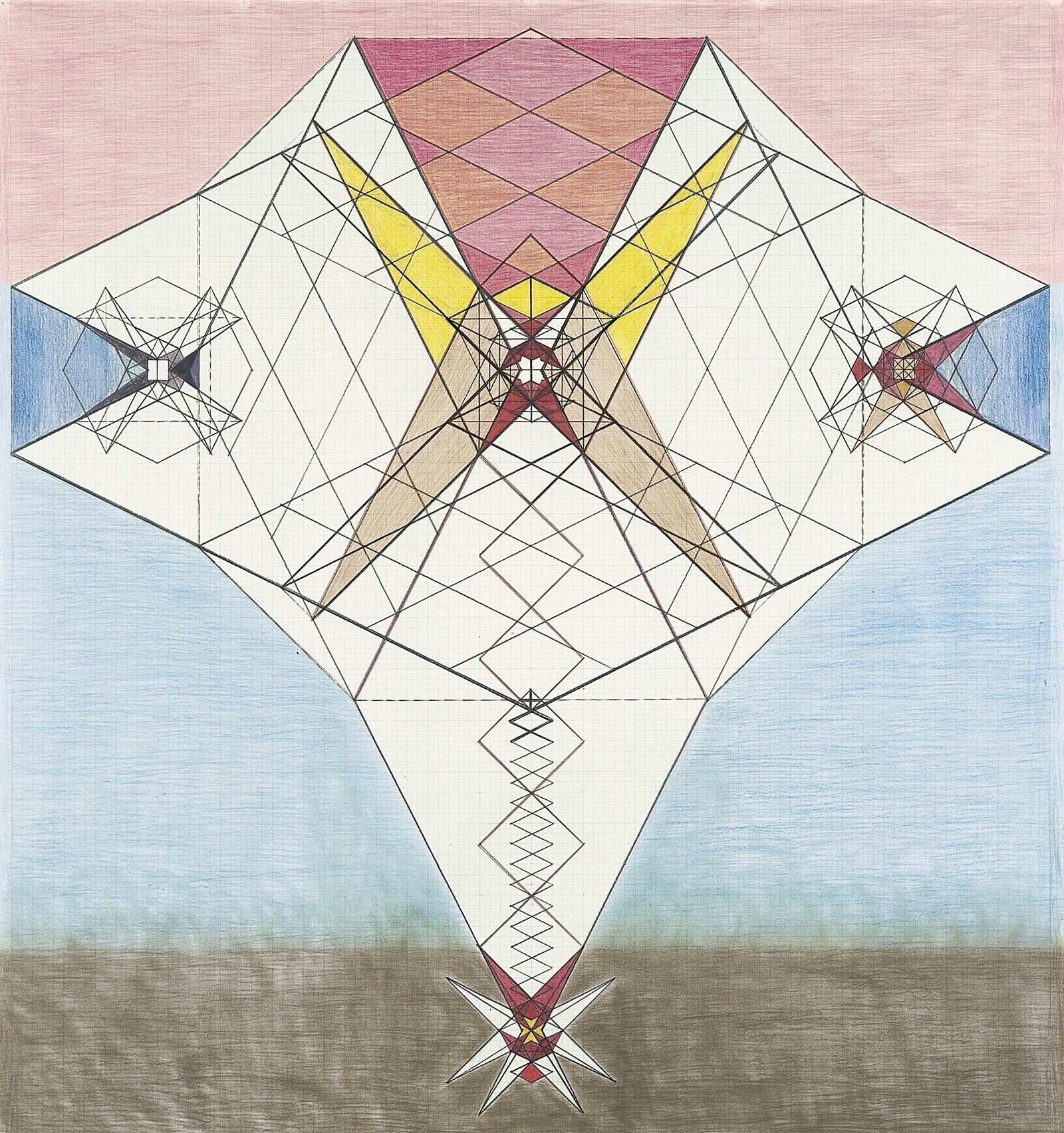

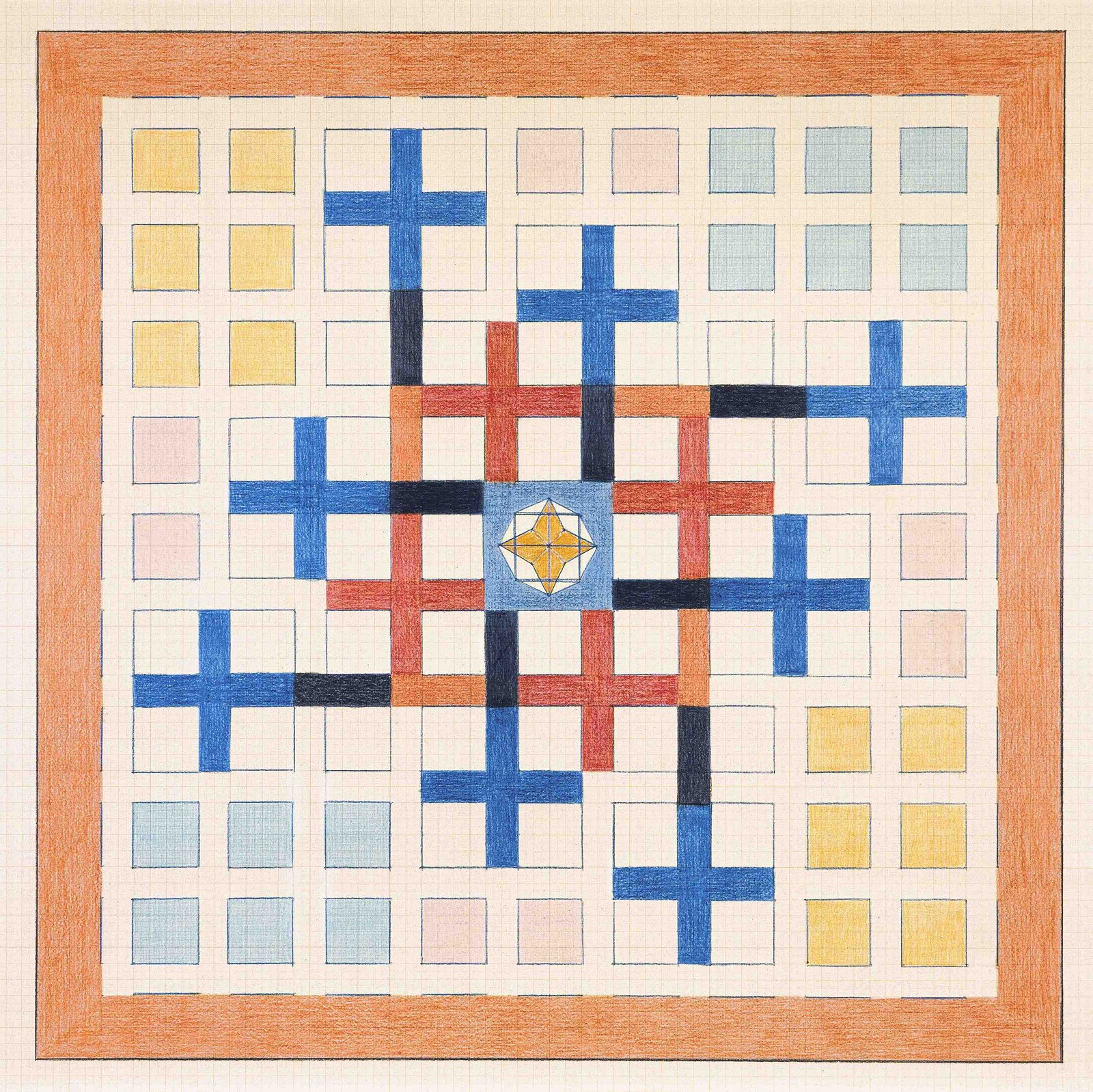

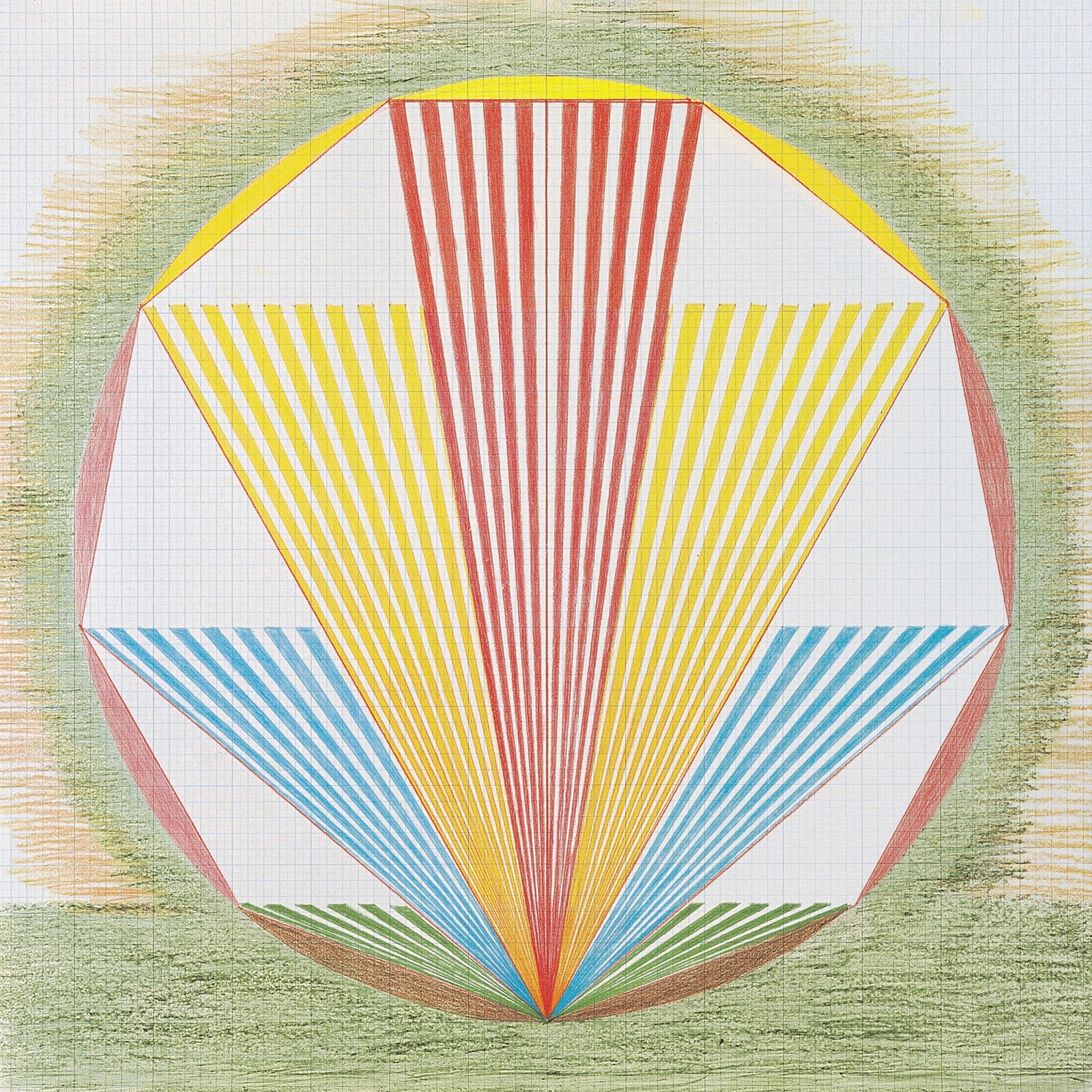

Kunz worked on millimeter graph paper, finely marked with brown or blue lines, which she cut into large squares and rectangles to produce around 400 drawings. Framed drawings tile the walls of the tall galleries or are hung singly. A few are laid flat on square plinth-like vitrines, reflecting how Kunz made them. She used pencils, crayons, and oil crayons, which she applied mostly in long, ruled lines, occasionally freehand, and sometimes in circles; lines that build up to generate blocks of color, occasionally emphasized by freehand washes. With these classroom supplies, Kunz created dizzyingly complex forms that occasionally stray into figuration. Most of them have at least one, if not two, lines of symmetry. As a result, they can seem simple from a distance. Examined more closely, the details and rhythms are hypnotic, while the symmetry’s interruptions engage and intrigue.

Work No. 392, a graphite wheel with washes of pink, green, and blue, thrums with the density of its radial lines. In Work No. 136, a central diamond of blue and orange crosses is enmeshed in a crystalline web of multi-sided shapes; at the four corners are figures resembling bats or butterflies. When the drawings are overtly figurative, they can be foreboding: in Work No. 99, a host of figures in the bottom half of the picture appear to wait for judgement from a commanding upper figure whose wing-like arms are poised over crucibles to either side. Across multiple pictures, a man and a woman are seen side by side, an embryonic child often superimposed on the female. Kunz’s shapes often emerge by virtue of fractional adjustments in the angles of her lines; in more abstract works, this means that edges are softened, the shapes limber up and begin to lift off the page. Sometimes they shoot out into fantastical architectures or dazzle the eye. The symbols she delineates are often familiar—artists have long been perfecting variations on crosses, circles, spirals, grids, hearts, and ladders, and assigning meanings to them—but not in these constellations.

Kunz’s parents were weavers and as a young woman she briefly worked in a knitwear factory. She received no professional training in art or any other occupation, and her drawing seems to have been a secondary element in her healing practice. Since her death, several monographs on her work have been published, in part, it seems, to establish her credibility as an artist as well as a naturopath, including sometimes contradictory accounts of how she made her drawings. Kunz worked standing and moved her pendulum over the paper, waiting to be guided by it before she made any marks. She did not calculate her forms in advance, though she sometimes noted figures on the margin, as is the case in Work No. 382. Each drawing was made in response to a specific question and followed a scheme of significance in which left denotes evil and right good, down denotes earth and up heaven. Across this are laid the four classical elements of air, earth, fire, and water.

Among the patients brought to Kunz for treatment was a boy whose father owned a quarry in Würenlos, in the Canton of Aargau, where she identified a healing element in the rock.1 The Würenlos site is today home to the Emma Kunz Zentrum, which maintains her archive and loaned all the works in the Muzeum Susch. Here, the few statements Kunz made about drawings in her lifetime are passed on orally to visitors of an exhibition of around 30 works. For some, the drawings are manifestations of spiritual activity that act as meditation aids or portals to that activity. Visitors can also spend time in the grotto, where unusually high energy levels are said to manifest. I am immune to the cave’s energies, but I am not immune to the tension that charges Kunz’s drawings: they elicit wonder and transcend their poor media and humble origins. The exhibitions at Muzeum Susch and in Würenlos make plain that Kunz’s work is significant to more than one audience—and that its spiritual and aesthetic guardians can be uneasy bedfellows. As a committed skeptic, I find Kunz an extraordinary artist thanks to the concerted complexity and wealth of the body of work she created, and the novelty she discovered with very spare means.

Kunz subsequently prescribed this matter, which she named AION A, to patients; it is still quarried and widely available in Switzerland today. AION A was originally called “Urschlamm,” or primeval mud.