I entered Gervane de Paula’s three-room retrospective by the wrong door, meaning that I saw this chronological survey in reverse order. By the time I came to view the works with which the exhibition is supposed to open—the artist’s earliest paintings, from the 1970s, show sunny scenes of life in his home state of Mato Grosso, in the Central-West Region of Brazil—I was aware of the dark clouds that would gather over his vivid later canvases and Arte Popular-inspired sculptures.

This knowledge of the artist’s development heightened my sensitivity to the uneasy details that creep into even the most bucolic of de Paula’s first works and foreshadow his later career. Barro Araés (1977), for example, makes plain the artist’s deep affection for his local neighborhood in Cuiabá, the capital city of Mato Grosso: in the foreground, children play with kites in front of their single-story homes while, further back, their mothers hang washing on lines strung across the communal grassy ground, the brightly colored clothes matched by the palette of the airborne stick and paper toys. You can almost smell the Sunday pamonha boiling in the food cart a man pushes past the houses. Yet my eyes were drawn to the dark depths of the trees, whose twisting branches convey a touch of menace, while the fast dashes of paint for the sky suggest that the summer breeze might whip itself into a storm and ruin both play and laundry.

In 1976, aged 16, de Paula started to attend Ateliê Livre, a free, ad-hoc art school run by critic Aline Figueiredo in Cuiabá’s historic downtown. It was here that de Paula developed his pictorial identity: in both the early joyful scenes of everyday life or the horrors represented later on, the painter’s lines are thick, the subjects strongly defined. The simplicity of the execution belies the complexity of composition. In his early twenties, de Paula began to introduce elements of fabulism. Among the most striking paintings of this period is The Farmer’s Daughters (1984). On a thick oak bed, the sheet patterned with bullrushes and ferns, two baby crocodiles face-off, their tails whipping against the head- and footboards. In a picture hanging over the bed, the two titular siblings are painted hugging each other in fear.

A tempestuous relationship between human and non-human animals can be parsed in this and other works, such as two untitled canvases of stingrays, one pricking the feet of an unlucky paddler, the other floating across a rubbish-strewn river bed. As de Paula’s career developed, he moved further away from these themes—and from his home state of Mato Grosso. The kites are replaced by guns and gaiety with crime, while the rolling hills give way to environmental devastation and dying animals.

Figueiredo included de Paula in a 1981 group exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, Rio de Janeiro, which led to his inclusion in the seminal “Como Vai Você, Geração 80?” show, in 1984, at the city’s Parque Lage art school. Here, de Paula became involved with the so-called 80s Generation of artists, including Beatriz Milhazes, José Leonilson, and Leda Catunda, whose portrait de Paula painted in the late 1980s. A fabric doll effigy of Leonilson, made in 2020 and here pinned to the wall, features the title of the work, “Leo can’t change the world,” in Portuguese on the doll’s miniature overalls: an early example of de Paula’s use of text, which became common in later works. Nearby, a painting that depicts Catunda in a carefree attitude is sharply contrasted by a self-portrait by de Paula, in which the young Black artist snoozes in his studio: dream bubbles depict white patrons gazing at his work in a gallery or hanging it in their homes.

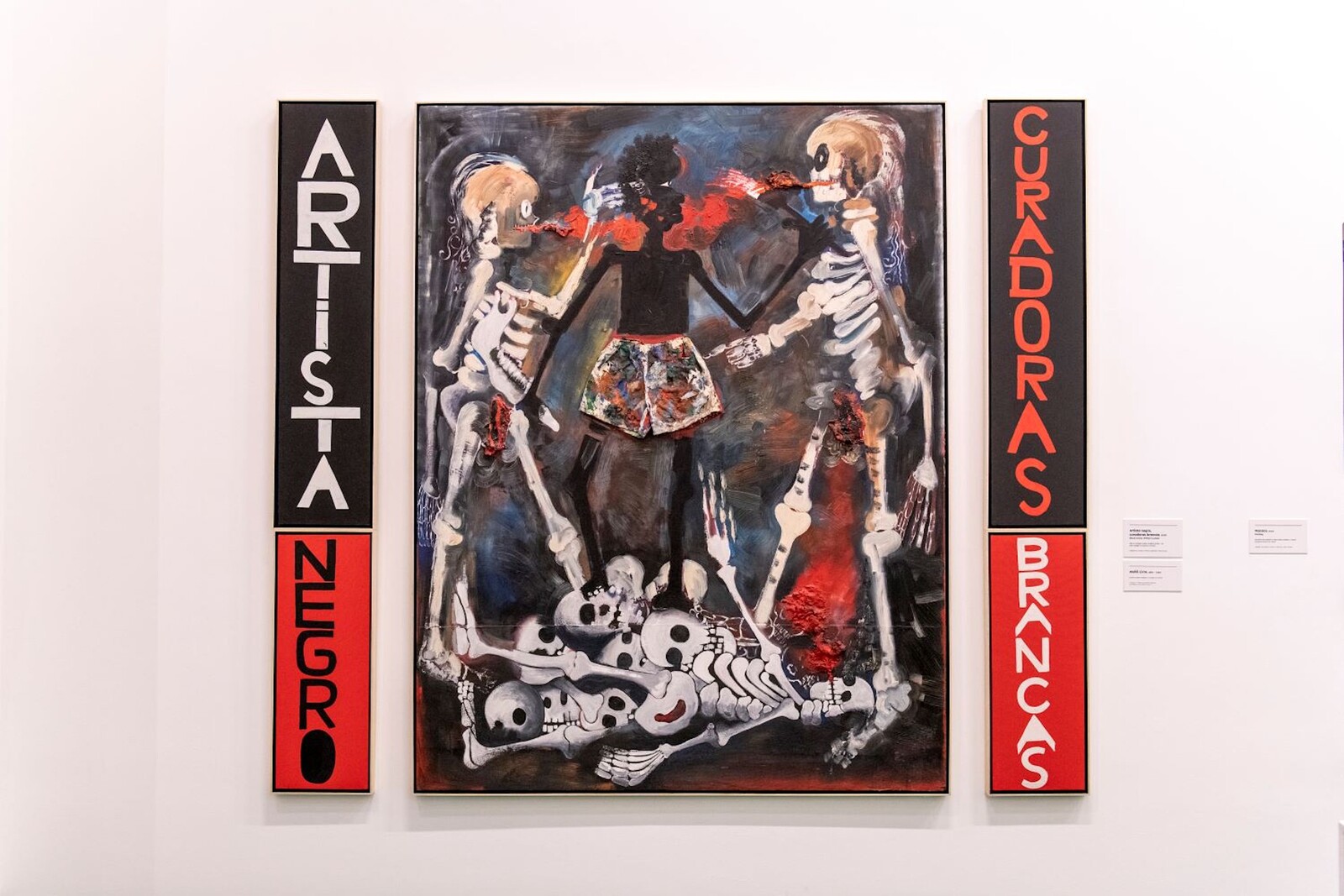

While Catunda and other white artists of the 80s Generation were based in Rio and met commercial success, de Paula, the only Black member of the group, chose to stay in Cuiabá, where he still lives. Later works more explicitly addressed race and power in the art world. In Black Artist, White Gallerist, a white woman in a geometric blue top and snazzy tights stares across at a screaming emoji-like Black face, while in Black Artist, White Curators (both works 2018), two white skeletons breathe fire in the face of a Black figure. Violence features in one of a series of work that riff on Philip Guston’s Klu Klux Klan paintings. In one, a smoking, hooded figure surveys another self-portrait of de Paula, like a critic considering his prey. Another shows two KKK members in distinctive white hoods riding a car through the Mato Grosso landscape. Alongside Guston, de Paula’s influences included German Neo-expressionism and Italian Transavantgarde, both appearing in force at editions of the Bienal de São Paulo in the mid-80s and which influenced peers such as Leonilson and Antonio Dias, who had more opportunity to travel to Europe.

The third and final room demonstrates that violence—racial, economic, and environmental—predominates in de Paula’s work since the turn of the millennium. Early paintings like Barro Araés seem rose-tinted compared to recent paintings such as Scene of Brazilian Life (2023). In this canvas, a row of heavily armed military police pose above a row of emoji-like Black faces. It’s a terrifying image. De Paula also turns with visceral anger to the environmental and drug crime that pervade the many areas of rural Brazil. SOS Burnt Paws features a series of traditional arte popular panthers and leopards carved from wood, their paws scorched black by the artist in reference to the forest-clearing fires of illegal mining and farming. Elsewhere, Drugs Mule, an undated acrylic on canvas, shows a cartoonish rendition of the animal with an x-ray view into its stomach that reveals it is packed with drugs.

Many of de Paula’s more declamatory recent works eschew subtlety, yet when the artist implicates himself in his narrative he achieves a greater complexity. A single phrase recurs across many of his recent paintings, invariably captioning pictures of hunters carrying their illegal kills or slain human bodies: “Arte Aqui Eu Mato.” It’s a play on the state’s name and “Art Here I Kill.” De Paula here implies, powerfully, that organized crime and the art establishment are two sides of a profiteering elite in a country which maintains one of highest levels of inequality in the world.