At the heart of Irena Haiduk’s recent exhibition “REMASTER” was a question: How can we remake the world using its existing infrastructures?

Across the two floors of Swiss Institute in New York, the writer and artist staged scenes taken from Mikhail Bulgakov’s novel The Master and Margarita.1 As in her previous exhibitions, these installations formed a set for Haiduk’s ongoing cinematic adaptation of the book, which satirised the Soviet regime by introducing the devil to 1930s Moscow. Apartment 50 was installed on the second floor and recreated Professor Woland’s living quarters, while The Variety Theater on the institution’s ground floor doubled as the setting for a program of performances and events.

The infrastructure underpinning Haiduk’s world is Yugoexport, her art company—or, more precisely, a “non-aligned oral-corporation”—modelled on a disincorporated Yugoslav clothes manufacturer and weapons exporter called Jugoeksport. Haiduk’s Yugoexport produces objects in the spirit of Yugoslavian material culture—rubbings, books, bags, shoes, dresses—in order to draw attention to current issues of labor, production, and exchange. To mark the exhibition, Haiduk worked with Johanna Rietveld to create a display at Printed Matter / St. Marks bookshop (on the first floor of the Swiss Institute) featuring publications including Bon Ton Mais Non (2013) and other “flexibly priced Yugoexport items.”

In the first of a new series of “conversations” designed to foster communication and prompt discussion during the international lockdown, Hendrik Folkerts speaks with Haiduk about Bulgakov’s novel, Yugoexport’s production models, living scenography, agency, economy, and sailors’ suicide songs.

Hendrik Folkerts: Let’s begin with Yugoexport. What are the economic models of production behind it?

Irena Haiduk: The first book I published, Bon Ton Mais Non, was a manifesto on polite art: a very short book, a buoyant thing. The price at which it was sold to people was based on their level of income. The book sustained me before larger institutions began to show my work. I believe in this distribution and economic model. I always thought that every person should be able to afford a part of the work, and that every book, shoe, dress, fabric, or rubbing on paper should equally demonstrate the maxim: “How to surround yourself with things in the right way.”

This became the logic behind Yugoexport, an art company that took up this flexible economic model, in which transactions are correlated to income. At documenta 14, in 2017, the incorporation of Yugoexport unfolded through various integrated works. The exhibition of my work at the Neue Neue Galerie in Kassel was partially funded by transacting Yugoexport articles—a dress and the “Borosana” shoes based on an old model designed for Yugoslav workers, for example—with the audience. If one believes, as I do, that nothing can be bought, then nothing can be sold; and if nothing can be sold, then contacting others with things you have made is not about possession. It is a much slower thing.

One can incorporate a company, but one can also incorporate what a company makes. We physically incorporate these things. They work through us, we attach them to our bodies, they nourish us, like food, like touch. You cannot incorporate a dead thing. This is why art must be alive.

HF: Economies of various kinds—financial, labor, libidinal, spatial, and physical, to name a few—play a major role in your work. How do you approach the relationship between economy and art?

IH: One of my first memories was the collapse of the National Bank of Yugoslavia in 1991, and the inflation of the national currency by three million percent. My deepest convictions come from these times, when money was paper, a beautiful drawing, and zeros were abstract mathematical concepts.

To me, the economy was never like the weather, a remote divinity. Instead, the economy is a place where we live; our house, our place of work. It is a place where any task, no matter how large and complex, can be brought into a scale of a human life, human action—the scale of bodies and hands. Any task worth doing is larger than can be accomplished in one go, but there is no task so great that it can’t be broken into smaller, more achievable parts.

HF: On that note, in 2008, you began using your exhibitions and installations as an unfolding backdrop for the production of a film now nearing its final stages. How have you composed the relationship between the physical space of your work and the film?

IH: I knew I could not make REMASTER, the film based on The Master and Margarita, in one take. So I broke it down. Every time I had an exhibition, new infrastructures and people became available to me. I took each as an opportunity to produce either the soundtrack or a video recording of a scene of the film. Production values increased, people and places changed, but the making of this work was continuous for me. It developed at the speed of my life and resources.

I am convinced that the way an environment is made remains deeply embedded within it, and with this memory an environment acts and influences people within it. Our environments shape us like our families. This fact makes one want to be generous: to make work that will describe the shape of those who live in it. This is an economy where everything desires and acts, everything is alive.

To feel this, the agency of things and environments, is the most intimate bond we can have with what surrounds us. REMASTER demonstrates the possibility of such encounters.

HF: It’s easy to have sympathy for the devil in The Master and Margarita, given that Woland exposes the hypocrisy of Stalinism even as he wreaks havoc across Moscow. What is Woland selling us?

IH: What Woland has sold to me is the knowledge that nothing can be bought. Those who think things can be bought also think people can be bought. We all know, especially in our time of perpetual emergency, that money has no hold on things. Love is the thing that binds. What we choose to love fully describes us. In The Master and Margarita, love motivates everything, and courage is celebrated as a requirement for the act of loving. In this book, cowardice is the greatest sin.

HF: During the course of the exhibition, The Variety Theater on the ground floor of the Swiss Institute became the stage for public events that also doubled as scenes for your film. Can you elaborate on that?

IH: On the opening night of the exhibition, we issued 500 keys to The Variety Theater. During the exhibition’s opening hours, the doors were opened to those who announced themselves at the front desk (or who had a key), and scenes from REMASTER were played every hour, on the hour. As the exhibition unfolded, the Variety went through a transformation that every prop goes through: it started to act as itself. A few weeks after the opening, on the evenings of February 13 and 14, it became a real theater, the stage for the “Cabaret Èconomique.”

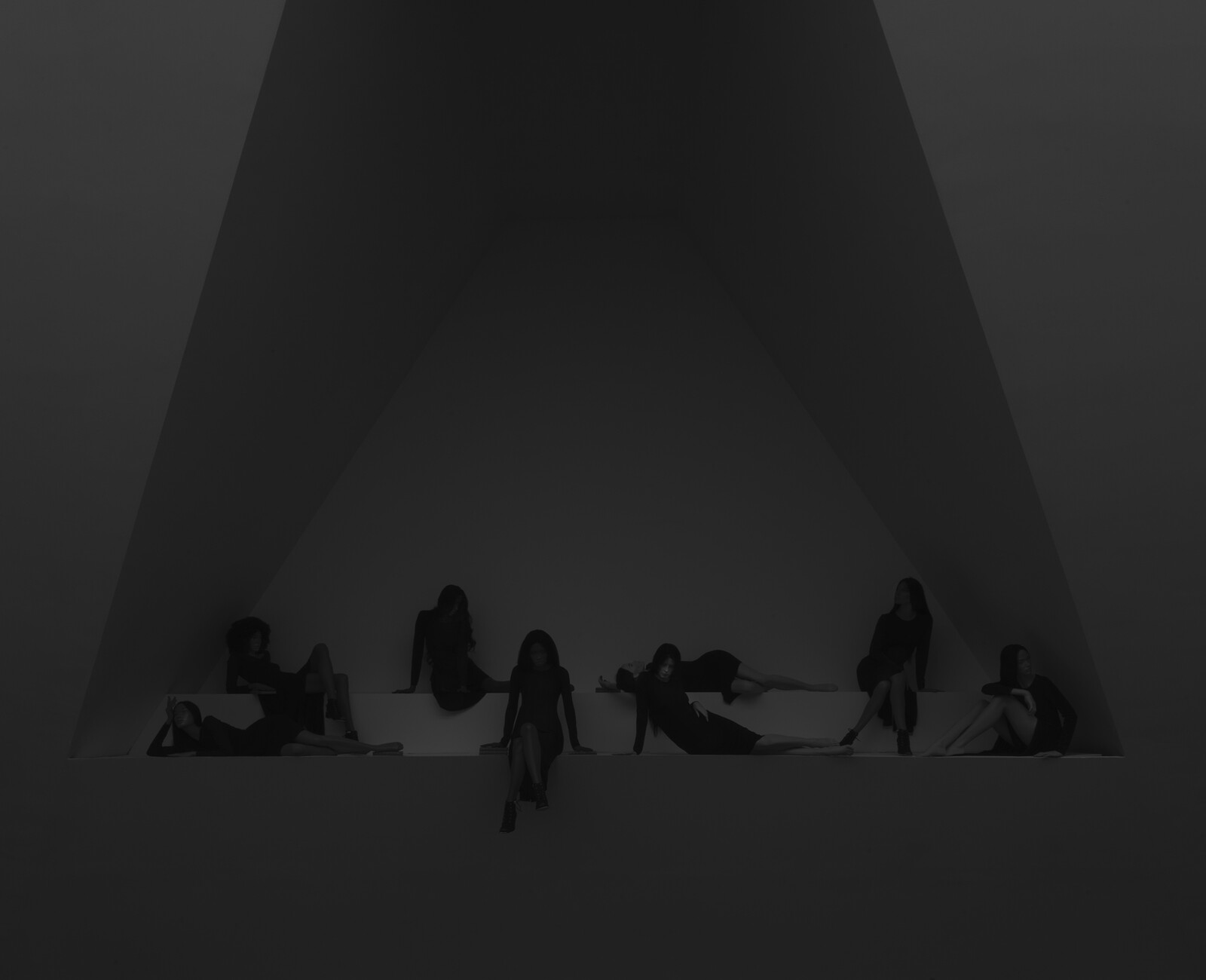

The “Cabaret Èconomique” was outfitted with latex, velvet, fringe, and other non-gendered fabrics, punctuated by minimal New Wave synths, choreographed to burn and stain, howling with pitch-perfect werewolves, and shipwrecked with sailors singing suicide songs. For the first time, I performed in my own work. I sang, I acted, I danced.

HF: The second floor evokes Woland’s apartment and includes sculptures-as-models (or models-as-sculptures) of previous spaces that have held your work, and a mysterious figure covered in what appears to be latex. How would you describe the life and agency of this space?

IH: When you enter Woland’s apartment, a figure under a vinyl cloak greets you. Is it a human or is it a thing? Does it matter? The fact that it acts means it’s alive. We get this uncanny feeling when something or someone in our presence is learning how to practice living, simultaneously becoming and making itself.

Art proves that all things want life and are alive. This is the archaic memory that all things have, despite how we abuse them today. To live with things as equals undercuts centuries of fucked-up colonial death drive: the possession-relation is broken, because what lives cannot be wholly possessed. To live with things in equivalence is to dwell in dignity and to undermine the mastering power. Our misunderstanding of possession as ownership and as a right, and our possessive treatment of things, is why we wait at the end of the world.

The exhibition “REMASTER” is a living scenography. Many of the spaces I create have within themselves the will to act, and this will reverberates. Scenography, as environment, acts constantly: it says who and what it is right now, how it came together, and what it demands of everything within its scope. It describes everything’s shape. Scenography is a form that imparts form. When something finds its form—when a person or thing becoming one with its purpose—love occurs.

That uncanny feeling. Is the figure alive or not? Forget the question. Listen to your body. Feel it.

HF: The word that emerges from this is “access,” if it can be stripped of its bureaucratic associations. These exhibitions-as-demonstrations ask the staging institutions to surrender a degree of control. They also ask visitors to live with things as equals, as you have so beautifully put it. Access speaks to the fundamentals of making public and, again, the notion of living scenography or agential space. Yet a more practical incentive for me to bring up this word is given by the 500 keys that you distributed at the opening of “REMASTER.” To what does this key give its “owners” access, now and in the future? What do they have a stake in or become agents of, once they enter that unspoken agreement?

IH: I equate the word “access” with the western concept of freedom. In English, the term “freedom” exists so that it can be a thing, an asset to trade: given, taken away, bought and sold. My mother tongue, Serbian, contains no such concept.

When freedom is traded it incites a fantasy of access as a right, a side effect of possessing freedom. In our world of rights-bearing individuals, freedom of movement is assumed to be one of those rights. But most people living under freedom’s spell enjoy no freedom of movement at all. Because that original trade happens in an economy of debt. And debt imposes the most severe limits on all movement. Debt immobilizes. The desire to possess, which engenders the borrowing that generates debt, curtails the imagination of other forms of desire. This is where the right to possess has brought us: a debt economy in which it is impossible to exercise the rights we claim to possess. This kind of freedom cannot be embodied. We might otherwise think of freedom as something we can be near, something we live with and deeply feel.

To gain access to anything, one has to be present. Access requires contact—it is the best kind of transaction. To stand at the threshold of a place you desire to access is to be aware of entering into a different set of rules, a new set of relations, a new behavior. To enter it is to become an actor and part of a scenography.

The key to the Variety Theater opens three doors. The other two are not at the Swiss Institute.

HF: How does this notion of access as interaction relate to Yugoexport’s ideology of production?

IH: Portability—the freedom of movement and the manual scale of objects such as keys and books—is a feature of most things in Yugoexport’s primary production model. A book is a habitable world that most people can afford. Yugoexport makes living companions that can be entered and embodied. If we practice transacting as scenographic interaction, then Yugoexport makes transactions. In this process, we dwell with things as equals.

At times, it is exhausting to argue that making something public means that it is automatically available—and available for sale. Money is an unreliable, destabilizing stopgap in a world that lacks the imagination to transact otherwise. I am 38 years old. I am using my body and my time, which I will never be able to take back. I labor. If you ask me what labor is, I can tell you that there is no answer. However, I can imagine a question that labor answers: “What is meaning?” Labor alone can never be compensated. Meaning is not something you can purchase, return, or refund. It is not something that should automatically be available, since it requires living.

The life of a given desire is so short, so ravenous, so selfish that it turns the object of desire to trash. Given its way, desire would dispose of everything. Yugoexport transacts slowly. We seldom display items. Even when we do, contact with a thing may not result in someone taking it away with them: it also provides an opportunity to meet people, show them things, listen, and discuss our relations to these objects. Transaction does not have to result in money changing hands, but those who do leave with a thing become a part of its making, another stage in the life of its production.

When a thing is alive, it takes care of us, and we must, in turn, take care of it. When a thing is alive it cannot be consumed, but is incorporated, embodied, and practiced. Everyone in the proximity of Yugoexport should be able to feel that, and this feeling cannot be bought.

We use money because we have to use what we have. We must begin to destabilize the absolute fact of monetary exchange. Our current system is our starting point towards a new one. We sustain ourselves as a studio of people and things. To demonstrate this economy, all facets of it, is to show that it is possible. Our studio is just one way of moving towards art as a field that embodies the principles and aestheconomics of living.

Written secretly under Stalinism between 1928 and 1940, the year of Bulgakov’s death, The Master and Margarita was first published as a book in Paris in 1967 after the manuscript was smuggled out of the Soviet Union.