Mexico City’s cycle of exhibitions often feels like a hamster wheel that never stops turning. This fall’s openings, however, set a more introspective and meditative—and perhaps not as obviously market-driven—pace. Yes, there was a lot of painting. But much of it felt quite unexpected in its deviation from recent attachments to the colorful and the figurative, and notably more mature than the pop-culture fixations that have crowded the city’s galleries of late. This approach to painting could even be broadly described as a form of disengagement or retreat: a movement inwards, embracing dreams and memories.

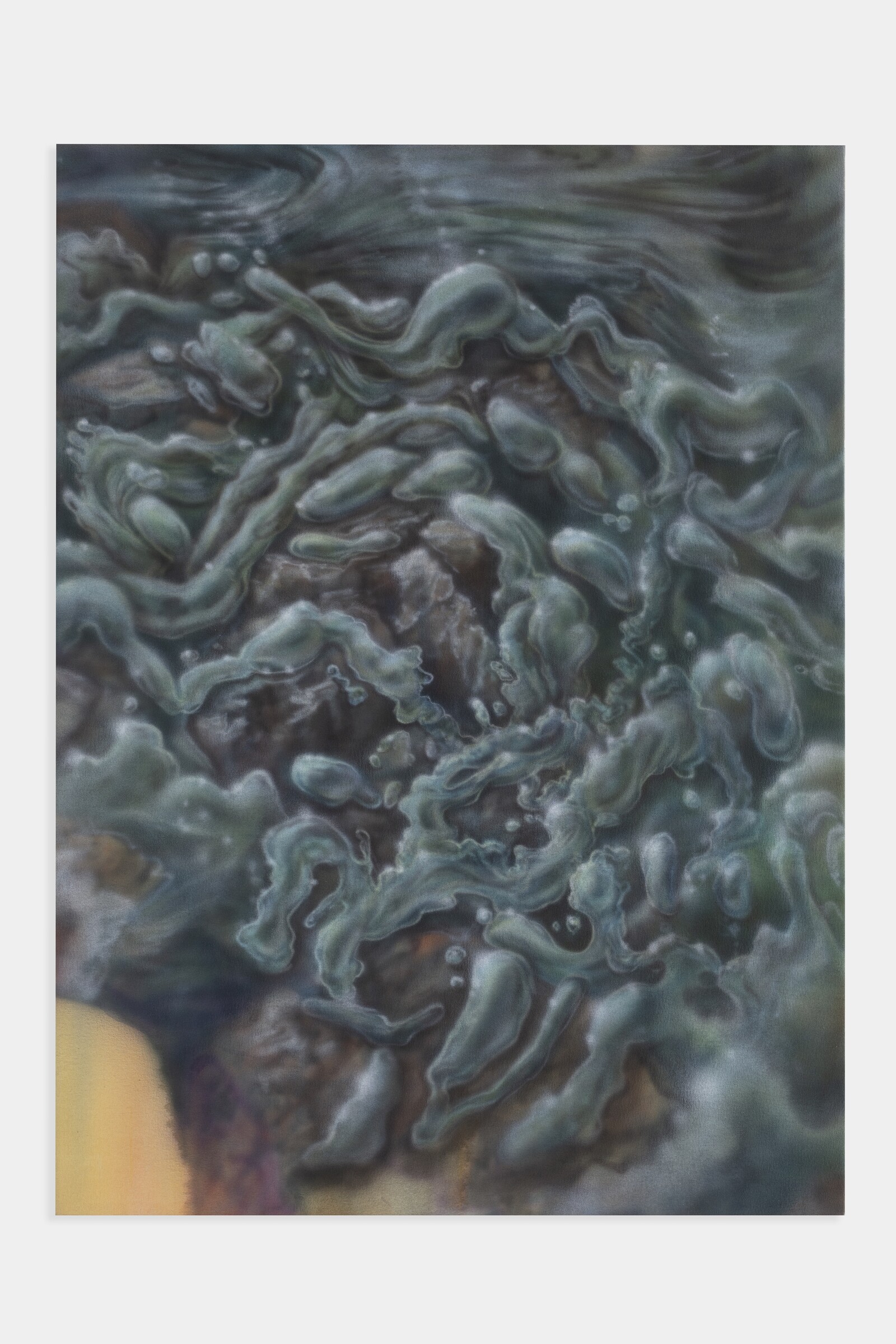

One such example was José Eduardo Barajas’s “Saliva,” his debut solo show at PEANA. Barajas’s practice to date has dabbled in post-internet aesthetics, creating loosely rendered CGI images of diamonds and currency falling from the sky. Earlier this year, however, for “Mnemósine” at Proyectos Multipropósito, Barajas replaced the ceiling tiles in a massive office space with tile-sized, loosely landscape paintings showing clouds, sunsets, dice, car rims, and hair (among other things) in reconfigurations of his earlier, CGI-oriented work. That show was a preparatory sketch, of sorts, for “Saliva.” In this tighter—and more impressive—body of work, Barajas magnified his experiments with landscape painting, and turned them inward. The resulting images are beautiful and implausible. In Baba [Drool] (2023), an elongated channel of water arches over shadowy cumulus clouds: a strange suspension. In Aguacero Viscoso [Viscous Downpour] (2023), a shallow stream roils over rocks to create uncanny, almost bodily forms, while a neon-orange spot in a corner resembles an accidental thumbprint on a developing Polaroid. Barajas didn’t forgo the excess of “Mnemósine” altogether, however, hanging sixteen large, portrait-mode canvases in a neat row. These display the advances in his acrylic and airbrush technique. Taken together, Barajas’s images felt visually intimate, the dreaminess of a past rendered fuzzy by its constant turning in our minds, snapshots of cherished memories hyper-stylized by our hearts and brains.

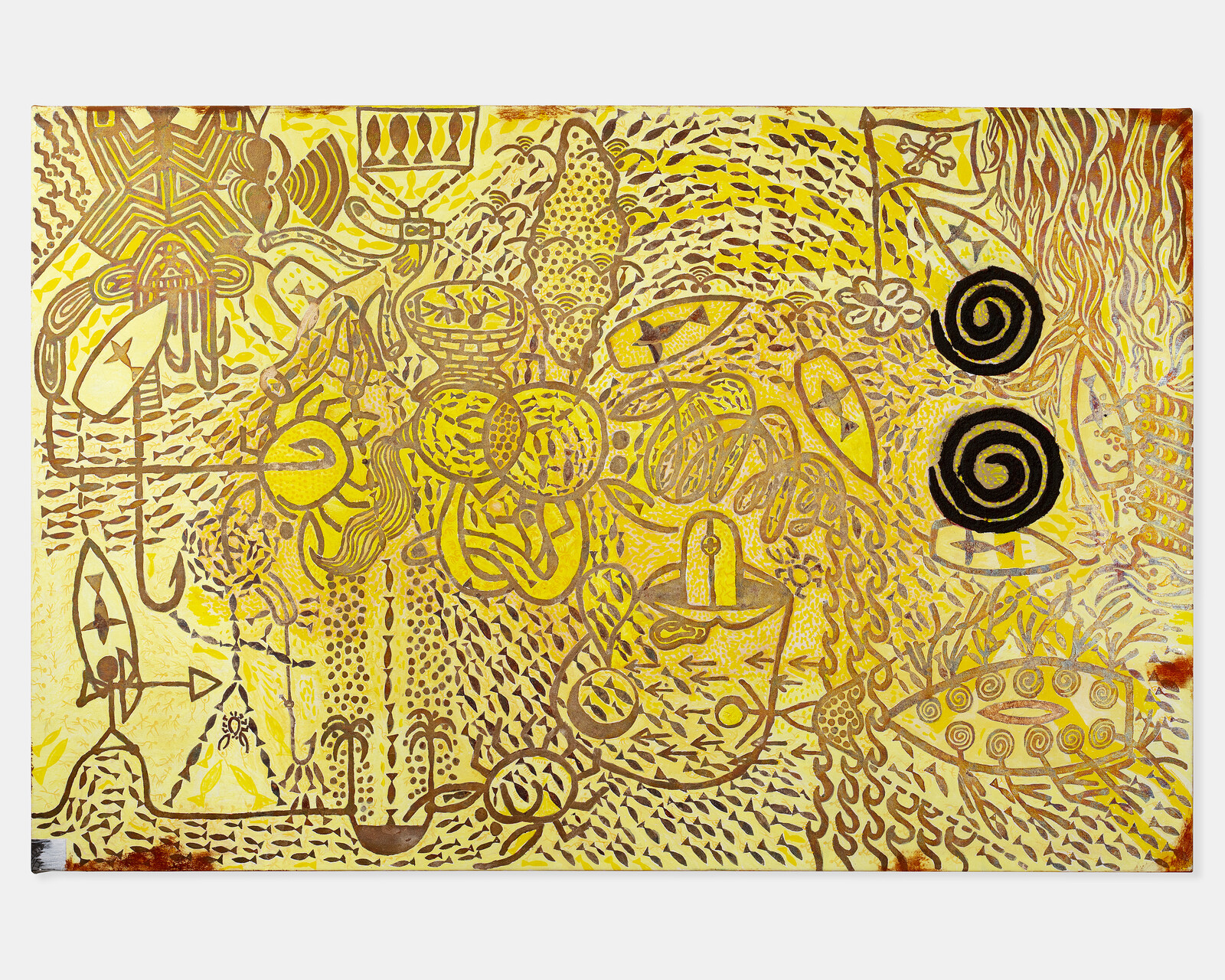

In an echo of Barajas’s dreamworld excess, Ramiro Chaves—an Argentinian artist well-known on the local scene for his photography—also took a major detour in his practice with “Escuela de Pescados” [School of Fish], a show of paintings, sculptures, and drawings at Agustina Ferreyra. Where Barajas used repetition and sharp close-ups to denaturalize the landscape, Chaves went all-out, adopting maximalism in an attempt to capture total experience. His mapping was obsessive and obstinate, seeming to explode throughout the space in bright—and not always pleasant—contrasts of colors and shapes. Stick figures populated a number of the works, as did simplified silhouettes of fishes, boats, clocks, bricks, roses, and frogs.

Indeed, to spend time in the room is to recognize the circular, yet expanding, compulsion. While the stick figures and fish that overcrowd the works are easily identifiable as such, and bring both municipal signage and religious symbols to mind, Chaves’s visual language owes its vitality to a clash of excess and saturation, of personal references and materialities—and the kinds of abstracted, simple shapes that so many of us scribbled in class while bored. As with doodling, these paintings feel led by process, without apparent predetermination. In Snorkel en el Escambrón [Snorkel at El Escambrón] (2023), the simple shapes form a sort of map—but of what? A flow of earthly energies, perhaps. A mysterious character, perhaps a spirit or deity, surveys the clashing scene.

Chaves was not alone in depicting interior landscapes characterized both by natural elements and psychedelic or metaphysical touches. The central piece in Andrés Pereira Paz’s “La Siesta de los Grandes Temas” [The Siesta of the Great Subjects], the Bolivian artist’s solo show at guadalajara90210, also featured frogs. Or something like them: these fluid forms were at once figurative and abstract, concrete and dreamlike. Sin título (Sapos) [Untitled (Frogs)] (2023) shows three pairs of amphibians facing each other and from the side against a solid black and yellow background. The simple composition was animated only by the ability of these creatures—which might have been paint palettes or odd craniums—to shape-shift as one looked at them.

Most of the works were hybrids of painting and collage. Sin título (Ángel de los 3 Elementos) [Untitled (Angel of the 3 Elements)] (2023), was truly peculiar. The main figure was a humanoid creature with a sea urchin shell for a head, painted in loose yellow strokes, sewn onto the black velvet canvas with the addition of two dull, brown feathers protruding from its back. That the tiny canvas hung at chest-height on a clothes valet of gold-painted metal, with a small round mirror for a face, only added to its strangeness. Sewn together from burlap and velvet, Pereira’s works evoke the kitsch, the amateurish, and other modes of practice unburdened by the hierarchization of materials and the marketization of identities. The stitched-together fabrics and unusual juxtapositions gave the show the feeling of a puzzle: the viewer’s task was to decipher its meaning. But this was elusive and unstable, like struggling to remember a dream upon waking.

In different ways, Barajas, Chaves, and Pereira’s exhibitions point to a determination to elude easy signification, and to skirt the discursive and referential qualities that have dominated recent painting trends in Mexico City. They were marked by a prolific—at times obsessive—approach, rooted in a diaristic urge to delineate and document inner topographies, with their endless undulations of memories and fantasies. In that sense, they created a space for slowing down, for repose.