Just 300 meters away from A4 Arts Foundation is the Castle of Good Hope. Built by the Dutch East India Company in the seventeenth century, the oldest surviving colonial building in Cape Town stands today as a symbol for a set of interwoven colonial relations: land expropriation, capitalist accumulation, racial subjugation, environmental degradation. Its very architecture—the pentagonal bastions, the high stone wall, the garrison, the prison—epitomizes the strategies at the heart of these formations: to dominate and exploit the commons. In South Africa, these strategies were articulated during colonialism, elaborated by Apartheid and endure, structurally and systemically, to this day.

Curated by Khanya Mashabela, “Common” asks how artists and activists, past and present, negotiate this destruction of the commons and its commensurate social relations. The first artwork one encounters upon ascending the stairs at A4 is a telling example of what is at stake in this exercise. Sue Williamson’s twelve photographs document Naz and Hari Ebrahim’s final weeks in a home marked for demolition in Cape Town’s District Six. Declared a whites-only area by the Apartheid state, the family was evicted and their home bulldozed in 1981. In those final days, amidst cups of tea and cigarettes and a feast for Eid, family and friends wrote on the walls of the house signatures, memories, and messages: one reads “The truth is on the walls of this house. The truth that is denied.” These tender moments of gathering and articulations of resistance are lamented by the final four images in the grid: the house, the eviction notice, the house turned to rubble, and the overgrown lot (this last photographed in 2008) where the house once stood.

This is more than the destruction of the commons. It elucidates the power of the state to alienate communities from one other, and not just in South Africa during Apartheid. Mark Bradford’s Life Size (2019), a paper cast of a Los Angeles policeman’s bodycam, reflects on the US state’s mandate to surveil and suppress those who threaten the carceral system. The bodycam, which purports to “protect” citizens from negligence and corruption, can—whether or not intentionally—reaffirm state power by readily disseminating and circulating images of police violence to the public. Gregory Olympio’s painting Paysage Grillage 10 (2021) depicts one example of the chain-linked fences that are commonplace across the world, from residential properties to detention camps. In Painting/Retoque (2008), Francis Alÿs laboriously paints a single yellow line at Paraíso, an ex-US military base in the former Panama Canal Zone, gesturing towards the implicit violence of a drawn border. Nolan Oswald Dennis’s column of globes, model for an endless column (2021), signals how difficult (but necessary) it is to imagine the world without the episteme of borders by placing a matte black void at its center.

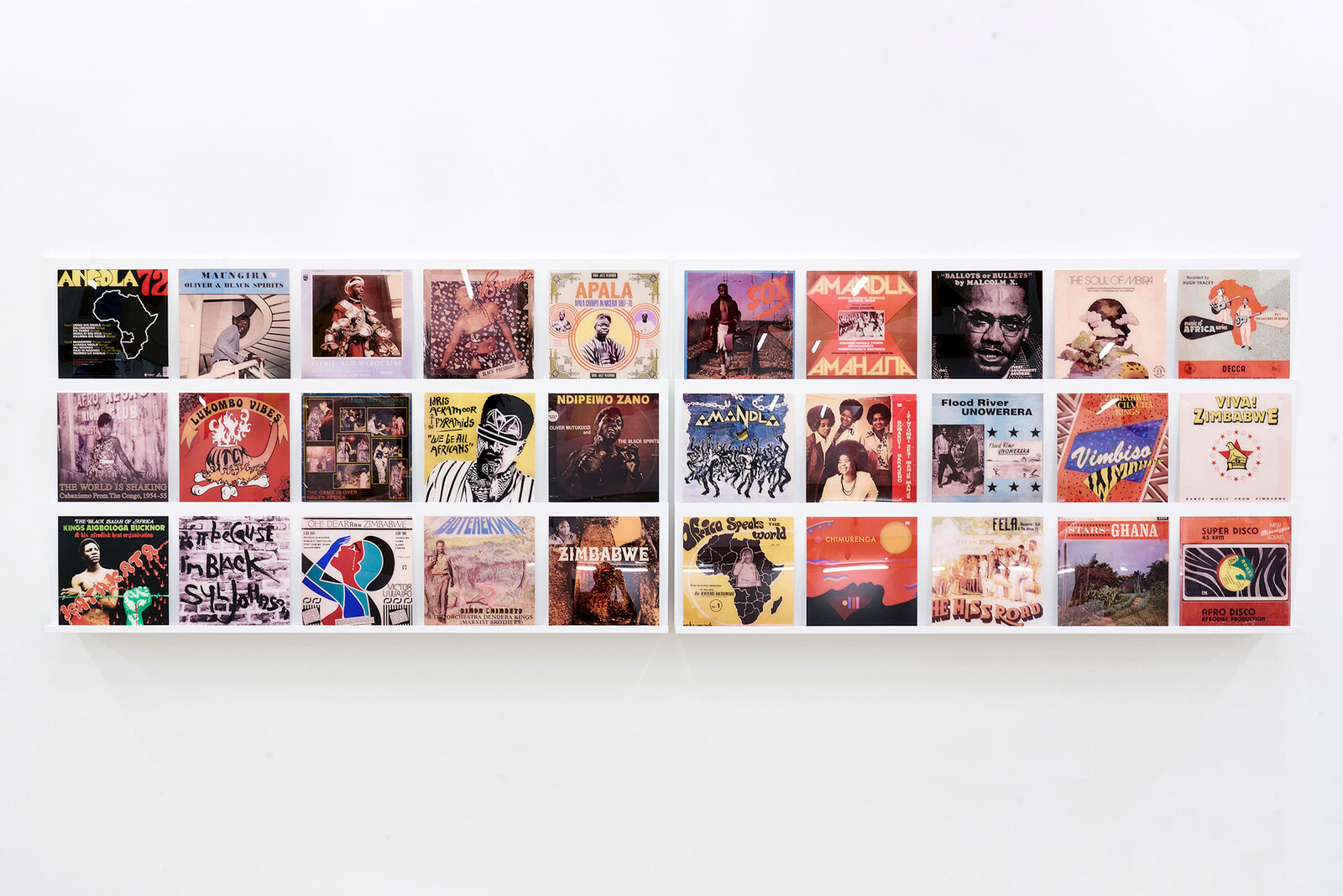

In the face of this violent world, what forms of sociality and solidarity can be fostered? In the main exhibition space, Mashabela has staged a library, complete with the books that informed her curation as well as a selection of records from Kudzanai Chiurai’s Library of Things We Forgot To Remember (2017–ongoing). This library of diasporic sounds and texts, which Mashabela refers to as a “knowledge commons,” is something of an antidote to the commercialization of everyday life. Countering this, Fabian Saptouw’s ISBN University Portraits Series (2015) remarks that the library is also a site of bureaucracy, where knowledge goes to be cataloged and archived, to become data and, in this way, to die. Hanna Noor Mahomed’s painting of the Google Docs icon performs a similar function by suggesting the thin line between knowledge circulated and data mined. What we think of as the commons, especially with regards to the digital, is in fact mired in the mud of the marketplace and its ever-present systems of surveillance.

If it is true that late-stage capitalism has commercialized everyday life, what can be constituted as the commons? Mashabela cites Charlotte Hess and Elinor Ostrom when she argues that “the commons can be as small as a refrigerator or as expansive as breathable air.”1 As such, she has included works that depict ephemeral moments of communal experience, from Gerard Sekoto’s painting of a community gathered upon a visit from the milkman, to Sabelo Mlangeni’s photographs of weddings, to Guy Simpson’s painting of a refrigerator. Lerato Shadi’s video, Mabogo Dinku (2019), captures this idea that commonality is continuously negotiated with gestures as simple as the wave of a hand, the point of a finger.

Occasionally, however, there comes a breaking point: quiet acts of defiance are not enough, so the people take to the street, reclaiming the commons. George Pemba’s 1960 painting of a political rally makes a hero out of the agitator who catalyzes these events, while Noor Mahomed’s site-specific installation nods to the mural as an agitating agent in the fight for public space. T-shirts from the South African History Archive (SAHA) and the GALA Queer Archive, hang as residues of the histories of collective resistance against eviction, conscription, exploitation, and marginalization in the South African context. In fact, some of these T-shirts would have been worn in crowds marching along the road between the Castle and A4, a common protest route towards Parliament.

“What kinds of structures can we create,” asks Mashabela, “that give us a better chance to be harmonious?” The T-shirt seems, to me, to be a good example. It forms an antithesis to the logic of the Castle. For its wearer it is soft and gentle, though its message is biting, defiant. It can be worn by anyone and, therefore, belongs to no one in particular. It is a synecdoche for community, and emits the “world-historical shine” of protest.2 At the same time, it’s just a T-shirt. Like the commons, we make of it what we will.

Charlotte Hess and Elinor Ostrom (eds.), Understanding Knowledge as a Commons: From Theory to Practice (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2007), 4.

Hannah Black, “Go Outside,” Artforum, (December 2020), https://www.artforum.com/print/202009/hannah-black-s-year-in-review-84376.