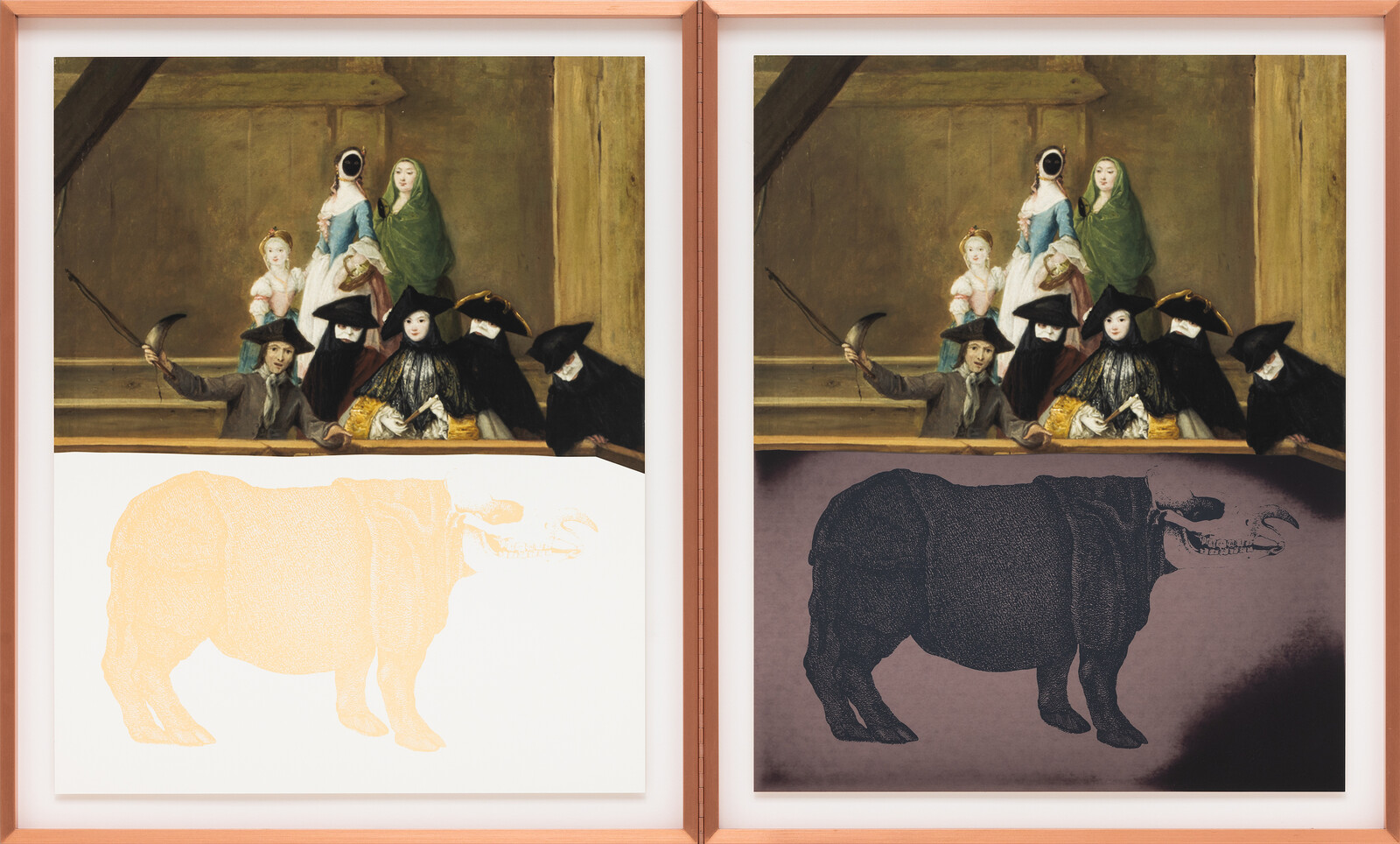

The formally diverse series of works that anchor Rirkrit Tiravanija’s new solo exhibition each highlight the accelerating inequity among living beings and propose tentative frameworks for their reconciliation. On entering the exhibition, the visitor is greeted by framed prints of five Old Master paintings which have been appropriated and adapted by Tiravanija. In twinned reproductions of Pietro Longhi’s Il rinoceronte (1751), for instance, Tiravanija has altered or partly obscured the original image of Clara—the first rhinoceros brought into Europe from Asia—as depicted in a Venetian carnival. The implication of the title (untitled, 2020 [we are not your pet], 2023) seems clear: to disrupt the idea that nature as distinct from humanity is something to be tamed and subordinated.

Then there are the mysterious, seemingly empty spaces in Jan Brueghel the Elder’s The Temptation in the Garden of Eden (ca. 1600). Where are the horses, swans, tigers, antelopes, and hares? I did as the gallery told me and shone a UV flashlight onto its surface, where now I could discern the peculiar, enigmatic shadows of departed birds (screen-printed onto the image with solar dust ink by the artist) perched on trees. They appear morbid, gentle, and undefined. Should we be thinking about the animals’ bodies through their invisibility? Their vanishment poses questions of memory and place, presence and absence. Here, perhaps, is one way of “seeing” the global extinction crisis that means more than one million species are at risk of disappearing.1

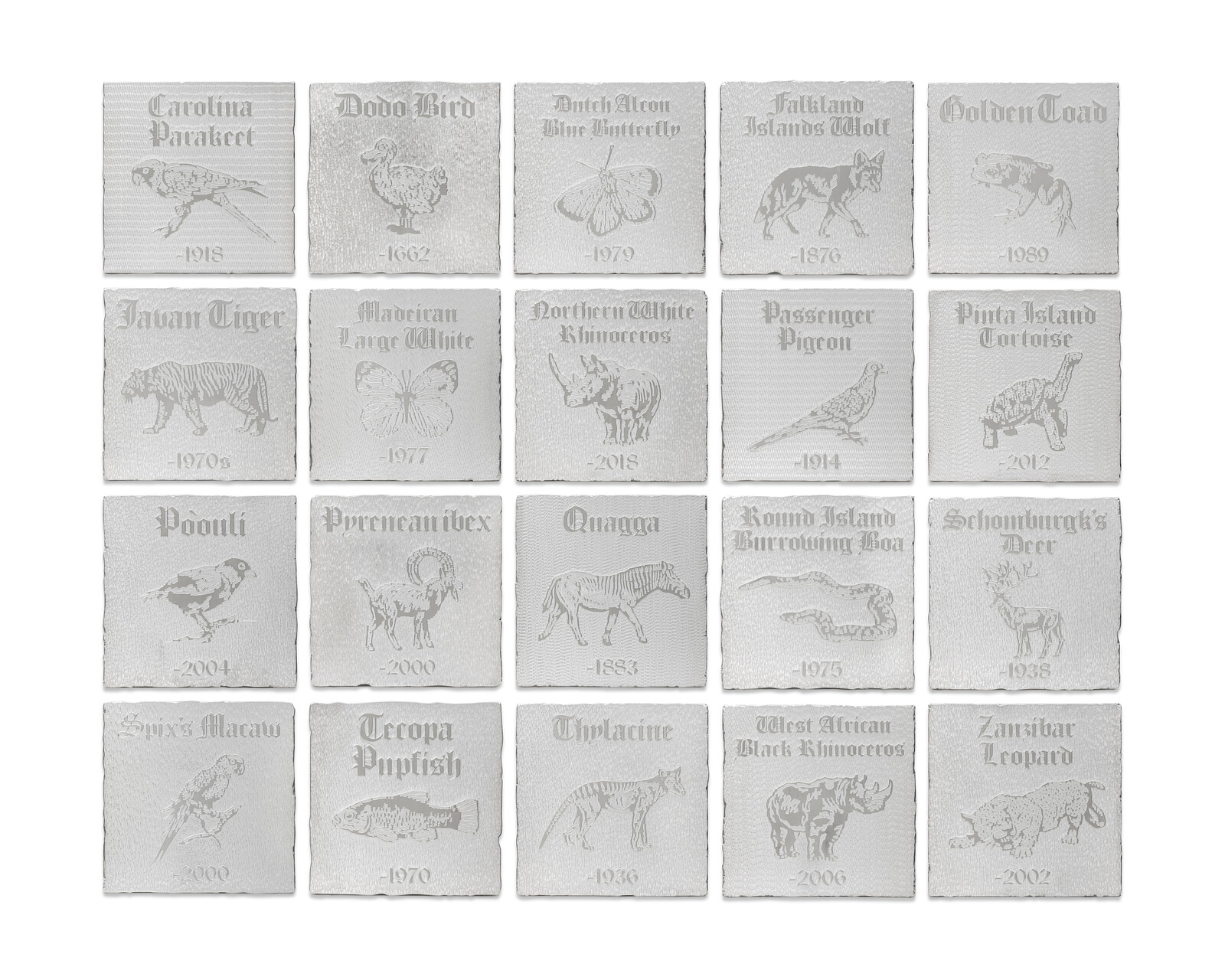

In an adjoining room, death is confronted directly and invisibility becomes a means by which to start the process of mourning. Silver plaques scattered across the gallery floor memorialize extinct species including the Quagga (declared extinct in 1883), Schomburgk’s Deer (1938), Spix’s Macaw (2000), the Zanzibar Leopard (2002), and the Pinta Island Tortoise (2012). Tiravanija’s installation untitled 2020 (nature morte) (2023) invites the visitor to crouch down and, through frottage, trace and recreate the images of the animals on these “tombstones” over and over again. The purpose seems to be to remind the viewer that their world cannot be separated from that which was once inhabited by these species, and to insist that they are shown the commensurate respect. I shuddered a little imagining the shades of these departed animals.

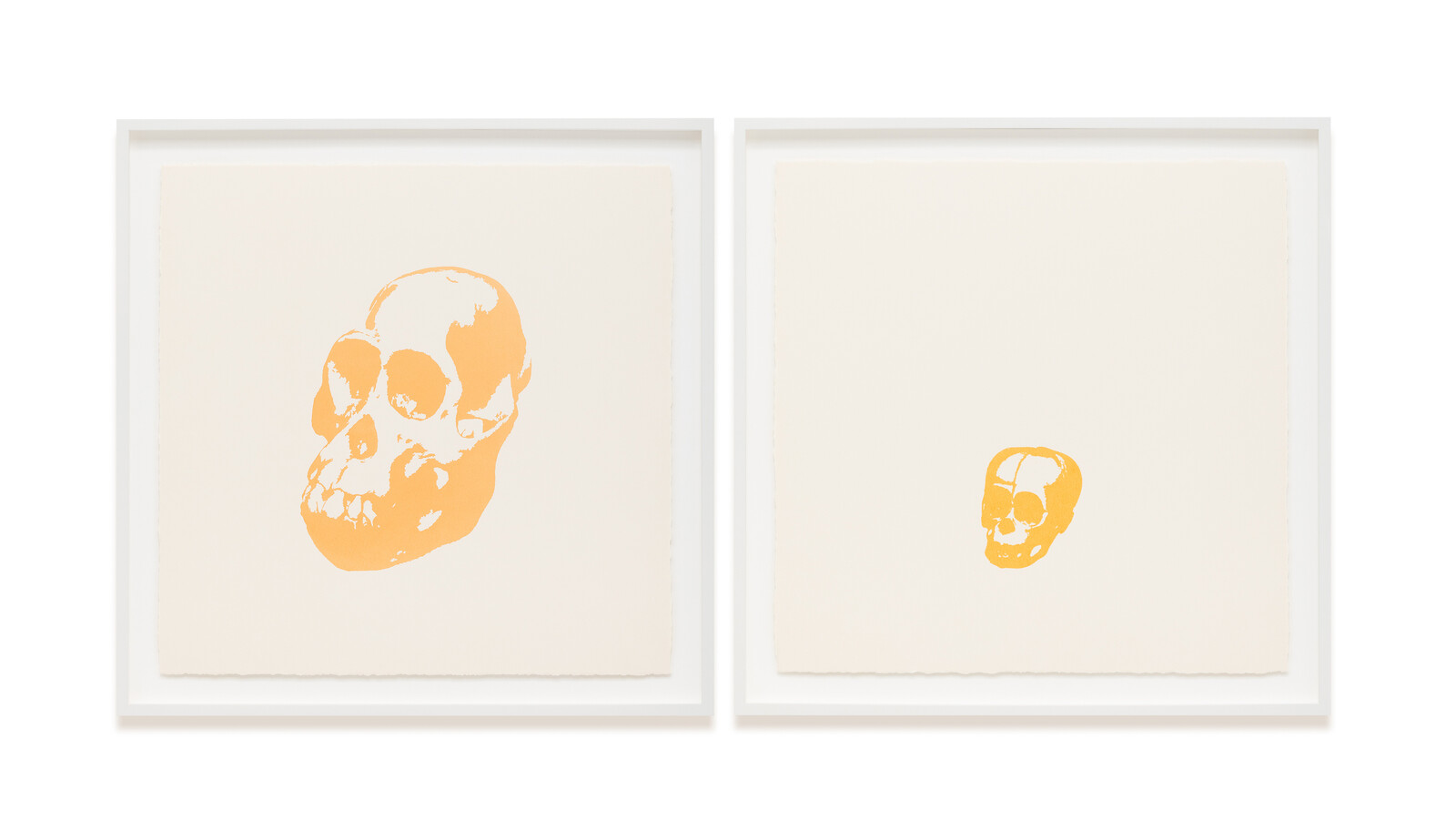

Down another dark hallway are seven spotlighted origami sculptures of animals, each displayed beside a large, mounted, unfolded sheet of origami paper marked with countless creases. Thus each sculpture is accompanied by a version of itself which has been unfolded or unmade. In Untitled 2020 (extinction series: tapanuli orangutan pongo tapanuliensis) (2023), for example, Tiravanija displays an origami sculpture of an orangutan beside an unfolded sheet on which is printed another “invisible” image that only shows up under UV light. The diptych print Untitled 2020 (we don’t recognize what we don’t see) (2023) presents images of the skulls of a female orangutan and her child. As with the tombstone series, these memento mori might also serve to remind visitors of the looming extinction of their own species: another tragedy that we choose not to see.

Among the “Missing Link” series (2023) is an eighteen-meter-wide stretch of hanging sheets of paper covered with thermochromic ink. The work is activated when visitors touch it with their hands, the ink responding to the corresponding increase in temperature. The color of the ink becomes lighter each time it is touched, until finally it vanishes. Here is an elegant representation of the small increments by which the visible world is pushed past the point of catastrophe. By alerting us to what is becoming invisible, Tiravanija illustrates the consequences of humanity’s present blindness.

Stephen Leahy, “One million species at risk of extinction, UN report warns,” National Geographic (May 6, 2019), https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2019/05/nature-decline-unprecedented-report/