When Charles Atlas quit as filmmaker-in-residence at the influential Merce Cunningham Dance Company, in 1983, after more than a decade, he decided to embrace a younger generation, a different continent, and a more public medium. These changes coalesced around the Pandean figure of Michael Clark, a former prodigy of London’s Royal Ballet School who in 1984 began to sketch out a punk- and club-inspired choreography with his own newly founded dance company. That same year, Atlas produced two works of videodance—a genre of experimental dance film, popularized by Atlas and Cunningham, in which choreography is designed for the camera rather than the stage.

These two films, Parafango (1984) and Ex-Romance (1984/1987), feature performances by Clark, Philippe Decouflé, and former Cunningham dancer Karole Armitage. They are set in vernacular places such as airport lounges and gas stations, and are spliced with news footage, presenter commentary, and video transmission signals. Both spotlight Clark as the enfant terrible of London’s post-punk underground, and the combination of his fauvist choreography with Atlas’s camp visuals captured a Baroque aesthetic that would characterize its queer subculture throughout the decade.

A Prune Twin, originally commissioned by London’s Barbican in 2020, consists of a multi-channel video projection sourced from the filmmaker and the dancer’s two most important collaborations of this era: Hail the New Puritan (1986) and its unofficial sequel Because We Must (1989), both originally commissioned for television by Britain’s Channel 4. Conceived as a New Pop equivalent to A Hard Day’s Night (1964), Puritan followed Clark through a “typical” twenty-four hours of rehearsal, press, errands, and general debauchery and featured many of his friends and frequent collaborators—Mark E. Smith, Brix Smith, Les Child, Cerith Wyn Evans, Leigh Bowery, and Trojan among them. The more amorphous Because We Must focuses on a series of Clark’s onstage divertissements at London’s Sadler’s Wells Theater and uses them as a springboard to the dancer’s backstage fantasies. Reimagined three decades later, “A Prune Twin” is as an exciting, anagrammatic exercise in form—as alluded to by its title, an anagram of “New Puritan”—that remixes both TV documentaries into an immersive, highly choreographed installation.

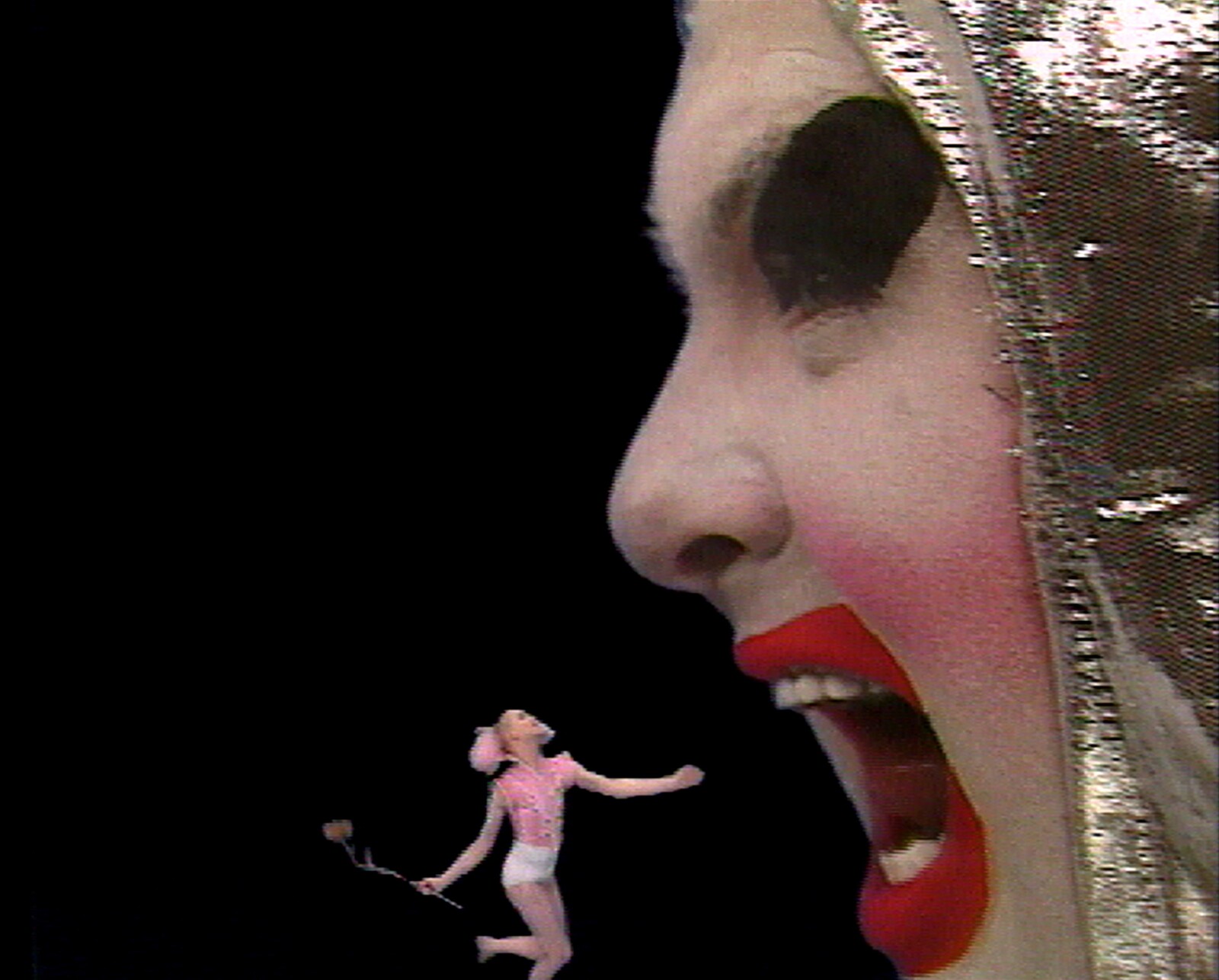

Spread throughout the gallery’s darkened, first-floor space on eight large screens and four monitors, the installation’s most prominent feature is, perhaps unsurprisingly, its frenetic movement—not only of Clark and company’s peculiar mix of feral gyrations and gender-bending role-play, but also the psychedelic sweeps of color, care of Bowery’s set and costume designs, and jarring fragments of music from The Fall, The Velvet Underground, and Bruce Gilbert, the rhythms of which were often influenced by the use of amphetamines. Cut up with no pretense of episodic narrative, the concatenation of sounds and images between screens creates its own leaping effect.

In a particularly oneiric sequence, a nude female dancer appears onstage and brandishes a chainsaw as three other dancers perform a pas de trois to a Chopin nocturne, while a neighboring screen shows quick flashes of Clark in make-up and bed clothes, wandering through the wings of Sadler’s Wells as if just having just awoken from deep sleep. Some of Atlas’s scenes are surprisingly muted and spare, as when Clark shyly explains to an interviewer his childhood love of dance in his native Aberdeen and his late-night habit of sniffing glue at ballet school—only to transition to a lurid chroma-key burlesque in which Les Child and other dancers, clad in Bowery-designed floral appliqué and crewelwork body suits (including matching fetish hoods), thrust and cavort to the Velvet Underground’s “Venus in Furs” (1967).

The hyper-saturation of image and music in the darkened gallery suggests the atmosphere of both a nightclub dance-floor and a storybook fever dream, a perfect encapsulation of Clark’s particular brand of anti-ballet—or what art critic Catherine Wood describes in a 2008 Artforum essay as his “intuitive understanding of ballet’s origins in pagan ritual and of dance as a drive”: “instinct, obligation, and symbolic social form […] forged in the discordant era of the 1980s.”1

Perhaps the most pleasurable aspect of “A Prune Twin” is the exhibition layout, which choreographs the viewer’s navigation of the space, approximating the fluidity of the onscreen movement. Throughout his career documenting modern dance performance, Atlas has remained equally fascinated by the informal scenographies just beyond the proscenium: the offstage and backstage, the threshold and coulisse, the everyday and the rehearsed. This penchant for off-centeredness is reflected in the staggered placement of the screens—which compel the viewer to weave between them, as one might through the wings of a theater—and the use of a video projection on semi-translucent surfaces—allowing the viewer to see the images on both the front and obverse sides of the screen, as if one were peeking backstage. Two screens and two monitors in a smaller cubby in the rear of the gallery suggest a separate black box theater, or even a club’s chill-out room, for a quieter, more intimate, experience.

Almost forty years after their first shared projects, Atlas and Clark—who still work together—continue to invoke comparisons to pagan figures, imps or tricksters who twist and contort their pasts inside-out and with a kind of puckish delight, while maintaining a Baroque approach to their respective mediums’ histories. Although Hail the New Puritan and Because We Must have long since entered the videodance canon, “A Prune Twin” offers a new way to appreciate Atlas and Clark’s extraordinary collaboration through the participatory functions of space and movement.

Catherine Wood, “Because We Must: The Art of Michael Clark,” Artforum vol. 47, no. 1 (September 1, 2008): 399–400.