When you land in Tunis, all the press materials are in a language you barely understand and despite everyone’s best efforts, you constantly end up lost, looking for places you never find. You’ll spend hours of research and late-night web searches, riding air-conditioned buses between scattered events, gathering as many stories from locals as you can, arguing with taxi drivers in a mix of English, French, and Arabic, stepping over an awful lot of dead cats, and running your fingers over exquisite carvings in ancient palaces. Despite all of this, what Tunis actually is (nonetheless how an international art festival might fit into it) remains as elusive as before you ever went. Somewhere in the mix of friends and acquaintances, the newly met and sometimes haunting characters and strangers that make up the voyage, you try to get a sense of the atmosphere of a place you never imagined you’d see. You find Tunisians to be warm and sad with a dark humor, the country crawling forward despite 2000 years of colonialism and more than a half century of dictatorship, its hope unbroken even if its spirit feels tired. In a car ride between parties at 3 a.m., a Tunisian sophisticate gives you a brief history of his country and somewhere in the narrative describes the first dictator after independence, however bad, as not the worst guy who ever ruled. He ends with the sentence, “Sometimes countries aren’t yet ready for democracy.”

The fifth edition of Jaou Tunis opened with a performance, but the real performance happened months before you showed up. Letters over letters, endless bureaucracies snarled and tangled, a series of compromises. The opening performance took place at L’Ancienne Bourse du Travail, an iconic building in Tunisian history. Built in the 1950s, it is a place where generations of trade syndicates and politicians would organize and deliver speeches, a deeply charged site of propaganda and promise (both made and broken). Located just off the Avenue Habib Bourguiba, the central thoroughfare of Tunis and the site of protests that began the Arab Spring and the overthrow of notoriously corrupt former President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. The revolution, along with the terrorist attacks that followed it, are present as a soft throb, not overtly in anything you see but pulsing in everything.

Organized by the Kamal Lazaar Foundation, Jaou Tunis takes the form of exhibitions, talks, and performances. In its first four years, the festival was organized by chief curator Lina Lazaar, who among other things inaugurated the first Tunisian pavilion in over half a century at the 2017 Venice Biennale and whose father established the foundation. For this year’s edition Lazaar stepped back and invited four female curators to organize individual sections, each based on one of the four elements: water, fire, earth, and air, along with the opening night performance in L’Ancienne Bourse du Travail, which the festival dubbed the Pavilion of Silence.

After months of negotiations, the Tunisian government had only given the keys to L’Ancienne Bourse du Travail two hours before the scheduled performance, not nearly enough time to set the stage. Organized by actor Bahram Aloui, the cast was composed primarily of untrained deaf actors for a performance that depended (for them) almost wholly on light cues, intermittently broken up by a small orchestra playing classical music. But the hulking light frame hung dead and unused. The producers just had too little time to make it work and so, despite months of rehearsals, the actors struggled with their cues. Sitting in the audience, we could all feel that something was amiss. The performers soldiered on admirably, with flashes of brilliant physical comedy, but even so the director was devastated by the crucial loss of stage lighting. There was something of a frustrated but undefeated shrug amongst the organizers. The voiceless, so often excluded, were given a venue, but just barely and under difficult conditions. Perhaps Aloui bit off more than he could chew, but the conditions weren’t great, though in a country and city still finding its force after so much trauma, this effort still really matters.

The following day opened the Pavilion of Water at the Church d’El Aouina, built by the French Protectorate as an air force chapel. Since then it had been a police station, a headquarters for a mafioso/government henchman, intermittently abandoned, and finally a boxing gym. The boxing ring stands in the center of the crumbling church and the scent of sweat and effort hangs in the air. In her first project in her homeland, Paris-based curator Myriam Ben Salah organized the exhibition “Water Pressure.” Balloon fish by Philippe Parreno (My Room Is Another Fish Bowl, 2016) float around the high ceilings of the neo-Romanesque church and bump into each other and the audience. Surrounding the main room hang curious and moving photographs by Ayla Hibri of the boxers who normally use the church/gym, the most striking and theme-appropriate of two sweaty young boxers pouring bottles of water over each other’s faces. It stands not far from a painting of bathers by Tunisian modernist Jellal Ben Abdallah, who died last year at the age of 96. The bulk of the exhibition is hung in small rooms off the nave: a monstrous creature made of olive oil and soap hulks in the washrooms, (Untitled) Kercha (2018) by Alex Ayed. Two moving-image works, Meriem Bennani’s Fly (2016) and Jessy Moussallem’s music video for a song by Mashrou’ Leila (Untitled, 2018), showed rather everyday experiences of folks from North Africa with humor and style. Animation is interspersed throughout Bennani’s video, like when a family member describes a wedding while her face turns into a waterfall (of tears? or sweat?). In Moussallem’s video, Arab women performed Busby Berkeley dance sequences against Leila’s song (it was matched by a very different and affecting performance by Ligia Lewis at the opening). These works deal with place in subtle ways without slipping into any easy clichés. High and low, literal and poetic, Ben Salah organized a group of artworks that felt playful without forgetting the strange beauty and intense struggle of a place.

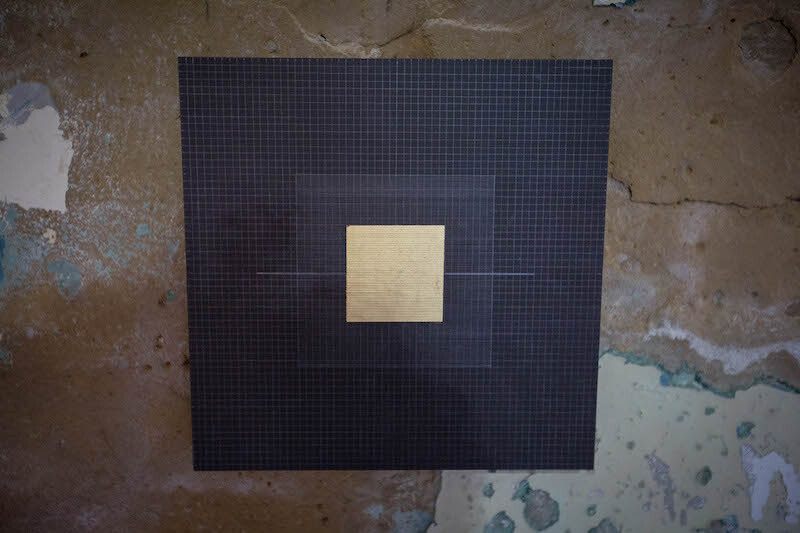

The three other pavilions dealt with their elements in direct and nuanced ways. The Pavilion of Fire, curated by Amel Ben Attia and held in a former printing press that produced some of the first independent books in Tunisia, brings to mind the burn of fire with the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi that sparked the Arab Spring and the toppling of the Tunisian government. It is a moment seared into the country’s memory, but other images of fire come forth from the exhibition: Kuwait’s oil fields set ablaze after the Iraqi invasion in Monira Al Qadiri’s video Behind the Sun (2013), coupled with quotations from Islamic television shows finding form in the grand language of Arabic poetry, and the fire that burned Habiba Msika, a famed Tunisian singer and dancer who in 1930 was set aflame by her lover, reflected on in a powerful homage made as a collaboration between dancer Asmahan Tlig and musician Haythem Achour in Curtains, 2018. In the Pavilion of Earth curated by Khadija Hamdi Soussi, the courtyard and adjacent rooms of neo-Moorish tombs become a site for exploration of archaeology. Works range from Hazem Harb’s collages on paper of historical images of “Palestine Reformulated Archeology Series #1-10” (2018) to Malek Gnaoui’s recreation of ancient architectural elements using scraps of broken bricks in 1,618 (2018) to create a Corinthian column rising up with the industrial force of a factory chimney. Aziza Harmel’s curated Pavilion of Air took place in Dar Baccouche, the ruins of an Ottoman palace with moldering paintings hanging in scraps unmoved for decades and the remnants of a lost and broken fortune in rooms tiled in beautiful patterns. The most haunting work in the whole festival, Narimane Mari’s Loubia Hamra (Red Beans) (2013), an 88-minute movie about a French soldier kidnapped by Algerian children sometime during the Algerian Revolution, reenacts an event from that war with mysterious sci-fi poetry. This video, alongside Naeem Mohaiemen’s Two Meetings and a Funeral (2017), appeared in Documenta 14 where Harmel was part of the team. Wandering through the palace, past the quiet sadness of an empty table filmed by video by Alejandro Cesarco in Shortly After Breakfast She Received The News (2012) and Kalavryta (2012), 2000 men’s ties woven into a tapestry by Fotini Gouseti, the art appeared like dreams of a ruined place, all of it mirages.

Stepping out of the Ottoman palace that held Harmel’s exhibition and into the streets of the Medina at night, the shops shuttered, fchildren playing in the long arcades, the whole festival felt like a kind of mirage. Days later, trying to piece the whole trip together, it was difficult to rub all these different textures and ideas into anything resembling a straightforward narrative. At a talk on your last day by artist Olivia Erlanger in the palace that belonged to Baron d’Erlanger, her potential ancestor (or just someone who shared her last name), spoke the palace’s curator, Mounir Hentati, who had taken care of the place since the family sold it decades ago to the Tunisian government and it became a center for Arabic and Mediterranean music. His dedication, scholarship, and care struck you with its force: how difficult maintaining such things through the changes of political tides and the neglect that comes easily when there’s never enough of anything to keep it going. It only made sense when you miss your plane onward, granted another few hours to stare into the magisterial blue of the Mediterranean under the dull dry heat, to breathe in the breeze and smog, to feel for a brief moment longer that such a place hardly requires easy summaries to make something lasting and meaningful.