I vowed to quit smoking (again) in March. Then March happened and discipline of any kind seemed naïve in the face of global chaos that has undermined the assumption that we can control our own fate. Now it is October and we are in the middle of a second (third, twelfth) wave and Runo Lagomarsino’s solo exhibition at Galerie Nordenhake, “I am also smoke,” does nothing to renew my resolve. It is an ode to the liminality of moments spent with one’s addiction in the face of existential instability.

On one level I read “I am also smoke” as an ode to smoking because it is bookended in the space by works that directly involve cigarettes. The first sculpture one encounters upon entering—Air d’exil (we smoke for the dead, we store the dead, but they are not dead) (2019)—is a neat double row of Duchampian glass globes filled with smoke exhaled by Syrian asylum seekers. The last work in the show, Yo Tambien soy humo / I am also smoke (2020), is a video of the artist’s father relating the experience of his first cigarette on European soil after fleeing Argentina with his young family following the 1976 military coup.

Lagomarsino is not interested in the romantic side of smoking à la James Dean or the emancipated Hollywood typists of the 1950s. His work does not evoke the affect of stealing cigarettes as a teenager and enjoying the dizziness with the girl you can’t take your eyes off in math class, shocked at her transgression and your own. “I am also smoke” is bound up with exile and the loss of a stable sense of belonging. It signifies the release of arriving after a long and uncertain journey and tasting the air of a foreign city for the first time in a place where you know you will have to survive, somehow, once you finish this cigarette. This is smoking as a ritual of resistance against crushing reality: futile, self-destructive, and irreverent.

Yo Tambien soy humo / I am also smoke is one shot tightly framed around an old-fashioned, 1970s-era postcard of Port Vell on the Barcelona waterfront. Christopher Columbus stands atop the 197-foot-tall column in the center of the postcard, pointing dramatically out toward the “New World.” The sea is tinted a too-vivid blue. The tram cars in the foreground are colored in an improbably saturated shade of red. There is a crease in the paper of the postcard that runs through the sky like a shadow mocking the enduring certainty of Columbus’s gesture. On a voiceover in measured, rhythmic Spanish, Lagomarsino’s father intones a story about arriving in Europe that he must have told many times. He sat on a suitcase, took out a cigarette, and decided to forget about Argentina and all the fear and death he and his wife and small daughter had left behind. Just for the time it takes to smoke a cigarette.

His is an absurd understanding of freedom. Exile is not freedom. The cigarette, also, is not freedom. It is an emblem of the plantation system that fueled colonial expansion in the Americas. Just as absurd is the fact that the speaker knows next to nothing about the city in which he seeks refuge, save that “Gaudi did not finish the Sagrada Família because he was run over by a trolley car”—like those in the video, in the shadow of Columbus. Violence lurks in each semiotic fragment of Lagomarsino’s work without ever totally undermining the sincerity of his subjects’ relief at having escaped a brutal revolution.

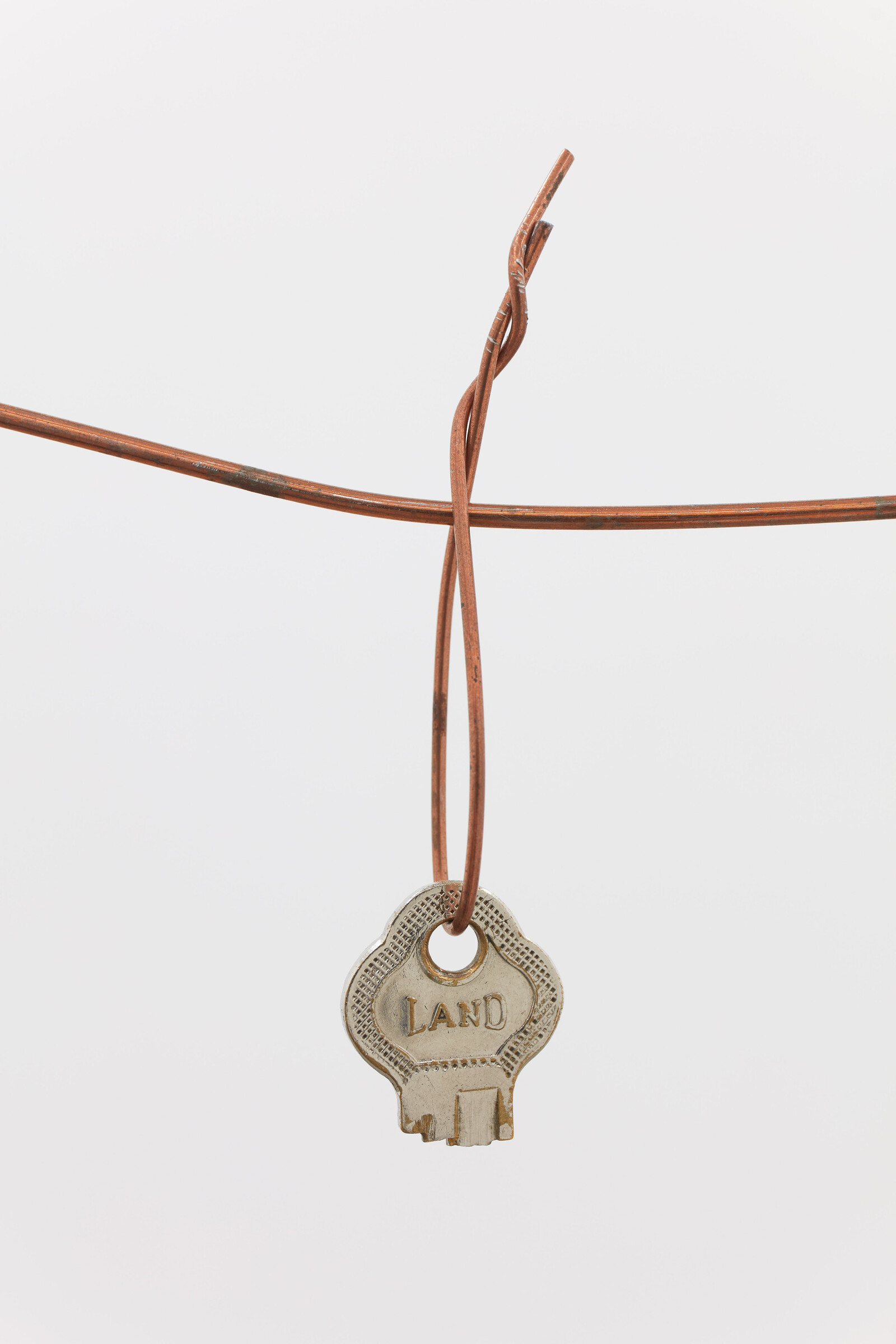

A sculpture in the middle room, entitled Language is a companion to empire (2020), footnotes this tension between submission and freedom. Two broken metal keys are suspended with copper wire from the arms of a simple iron cross. A word is emblazoned where the brand would appear on the head of each key. One reads “Land” and the other “Gold.” The words are engraved at the place where a finger and thumb would rest as the key is inserted into a lock and turned. This is language meant to be absorbed into the body rather than read. Amputated as they are, neither key will ever unlock anything again. No finger will ever rub the words inscribed in them unconsciously, one hand in a jacket pocket on a journey home. They constitute the broken promise of ownership and exclusive access. Crucified, they stand as a warning of the violence that stems from such fantasies of freedom.