Since the advent of the US’s “War on Drugs,” popular media representations from Breaking Bad to Intervention to Celebrity Rehab with Dr. Drew have mirrored the political consensus on drug addiction, reducing it from a deeply political phenomenon driven by markets—both the pharmaceutical industry and underground economies—to a dialectic of stylized euphoria on the one hand and abject depravity on the other. Both the media landscape and the rehab industrial complex drip with a Protestant ethic that pits puritanism against hedonism: addiction is rendered as a moral failing, not what a growing scientific and sociological consensus understands as one symptom of a profit-driven healthcare system, systemic racism, and gross income inequality.

Nan Goldin’s work is antithetical to ideas of addiction that, by painting it as a personal failing, obstruct any substantive response to a devastating health crisis in favor of subjecting vulnerable populations to punitive violence. Against this backdrop, Marian Goodman Gallery’s first New York exhibition of Goldin’s work highlights several major pieces, including Memory Lost (2019–21), an impressionistic slideshow of life seen through the experience of addiction; its thematic sister Sirens (2019–20), a video work approximating the hypnotic ecstasy of being high; and The Other Side (1992–2021), an update of an older slideshow depicting the lives of Goldin’s transgender friends over the course of four decades. Goldin herself is a survivor of the opioid epidemic. Prescribed OxyContin for a wrist injury in 2014, she developed an addiction that nearly destroyed her career before she went to a detox clinic in 2017. That same year, she founded Prescription Addiction Intervention Now (P.A.I.N.), which has organized direct actions against art institutions including New York’s Guggenheim and Victoria & Albert Museum in London to highlight their financial collusion with the Sackler family—and thus their complicity in the widespread damage for which Purdue and other pharmaceutical companies are responsible—and now does policy work to expand harm reduction services.

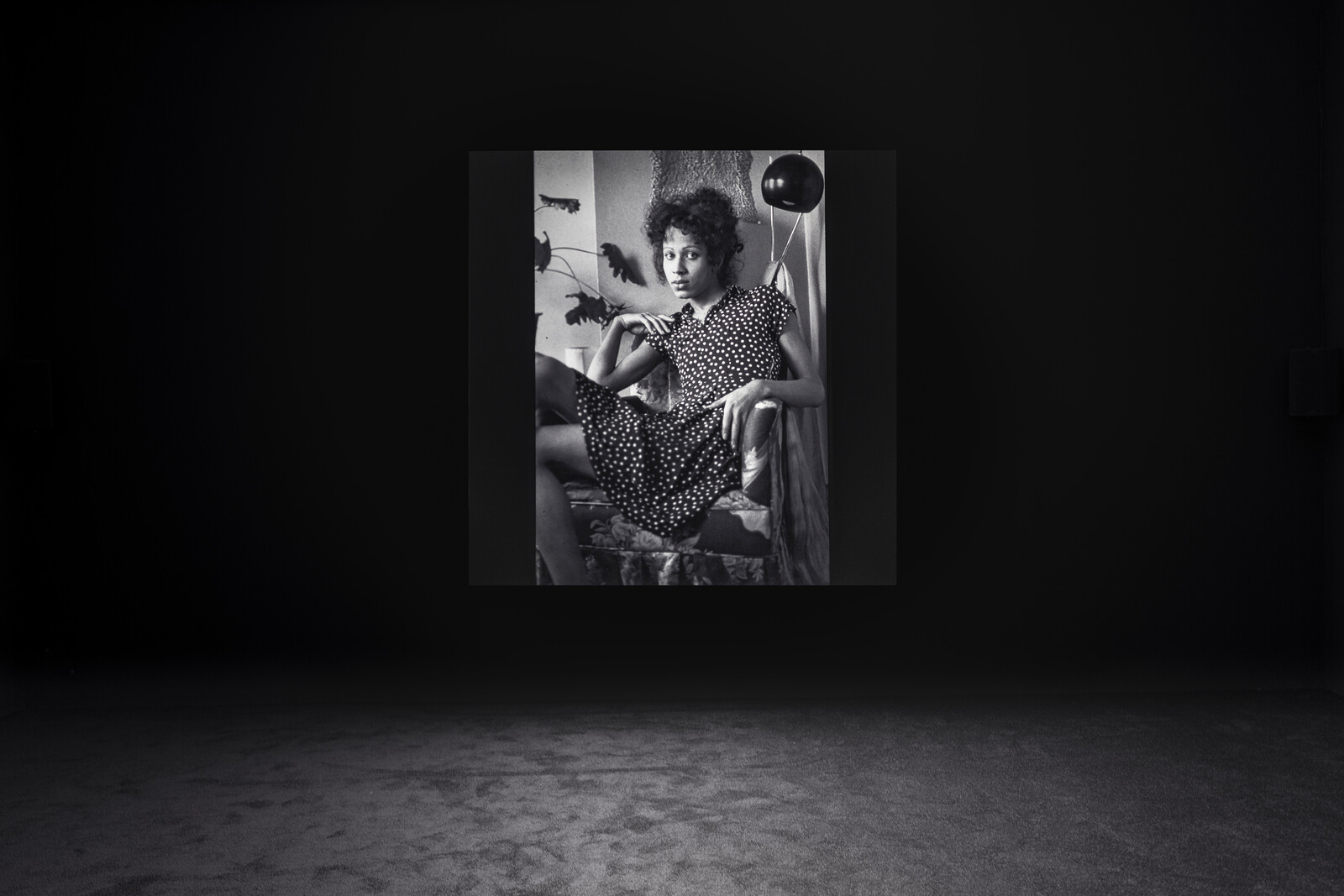

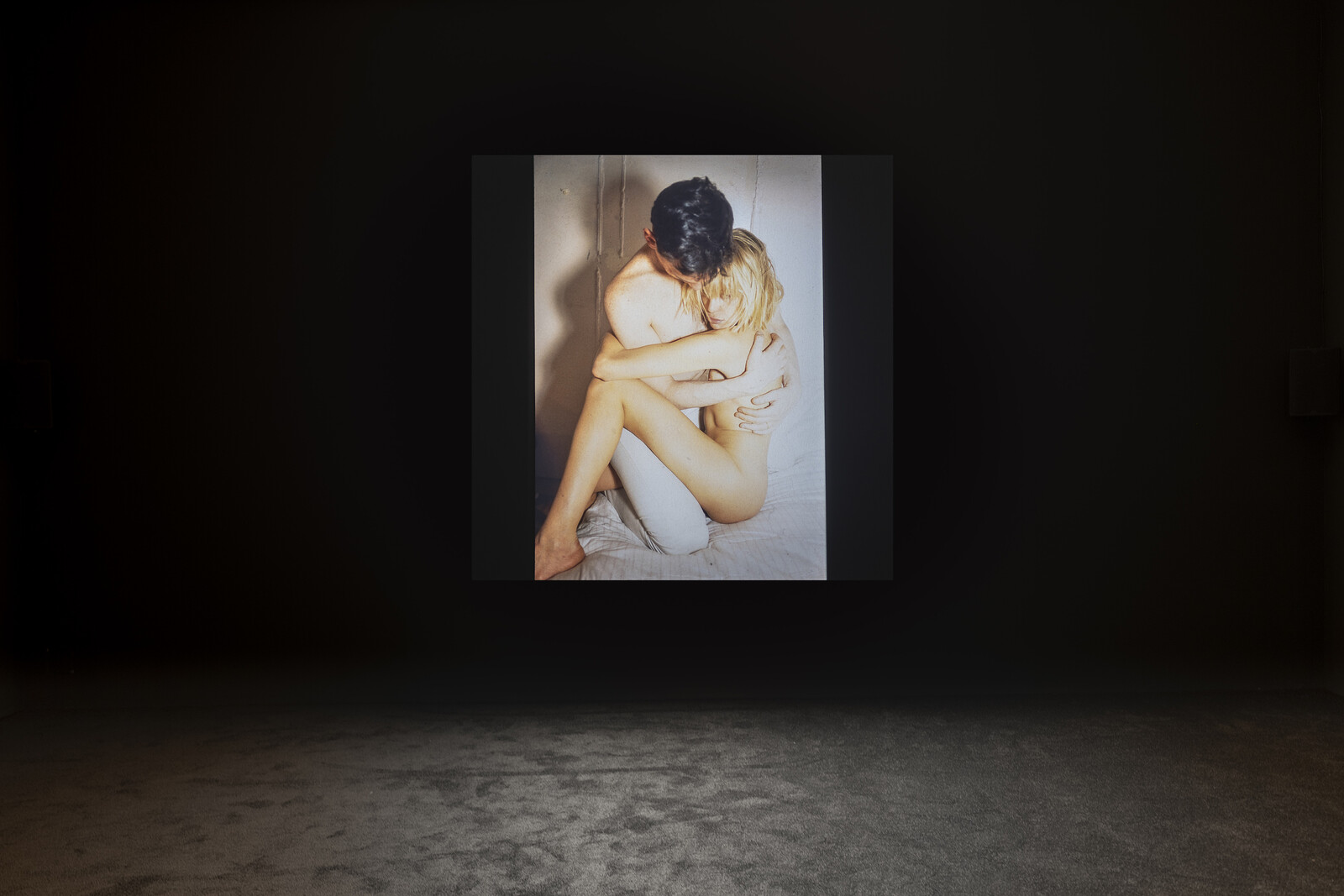

Art by its nature tends to aestheticize its subjects—in this case, those living with drug addiction as well as transgender urbanites. These are populations whose lives are either rendered invisible or, when given visibility, too often exploited and sensationalized. Goldin sidesteps these tendencies by allowing her subjects the dignity of banality. The role of transgender activists in changing attitudes to binary gender, patriarchy, and homophobia can hardly be overstated, but the idea that the trans experience is inherently “revolutionary,” to quote Goldin in The Other Side, is at odds with what feels truly radical about her work in the age of Diversity Officers and shallow inclusivity politics now synonymous with LGBTQIA rights discourse—as opposed to the liberation politics espoused by many of our trans elders. Each of her trans subjects is beautiful—fabulous, even—but Goldin also permits them to be tired, melancholic, to party, to commute. The images in The Other Side put us in rooms with transwomen and glittering drag queens donning makeup before a night out, dancing in clubs and ballrooms, but also lounging at home, bathing, playing carnival games, fucking, and sleeping. One image in particular (Misty and Jimmy Paulette in a Taxi, 1990-91) typifies the gentle hand with which Goldin places these women before her audience. Two women sit in the back seat of a cab—one with blue hair and a sleeveless vinyl turtleneck, her head slightly tilted, the other with her blonde hair up and a torn fishnet top—perhaps en route to an event, perhaps home, both looking coolly towards the lens. This demystification of her subjects’ experience is not to deny the very real violence put upon transgender people in the US—Black and Indigenous transgender people disproportionately—but by allowing transwomen an experience beyond just romance, triumph, and tragedy, The Other Side is a more humanizing project.