Arranged into families following a meticulous taxonomic logic, the almost 300 drawings presented at Drawing Center reveal the extraordinary bestiary that Joan Jonas has been compiling over five decades.1 Jonas has a unique capacity to traverse and merge artistic fields as varied as performance, sculpture, environment, and video installation, but what is illuminated by this exhibition, carefully curated by Laura Hoptman with Rebecca DiGiovanna, is how drawing runs through, across, and within every means of her expression, accompanying the development of her career from the 1960s to the present.

The show also demonstrates how the artist has been bringing these disciplines together through drawing, as it becomes a practice akin to performing and editing, in a do-repeat-redo-repeat-erase-do-repeat method that connects the mind, body, and hand until the form emerges. Two drawings flank the entrance to the show (all works are untitled but classified by a reference number, in this case JJ084, circa late 1990s, and JJ085, from 2012), which also becomes its exit. These are two naked female torsos, as imposing and as head-, arm- and feet-less as the Winged Victory of Samothrace (190 BCE), made in the context of two live performances.

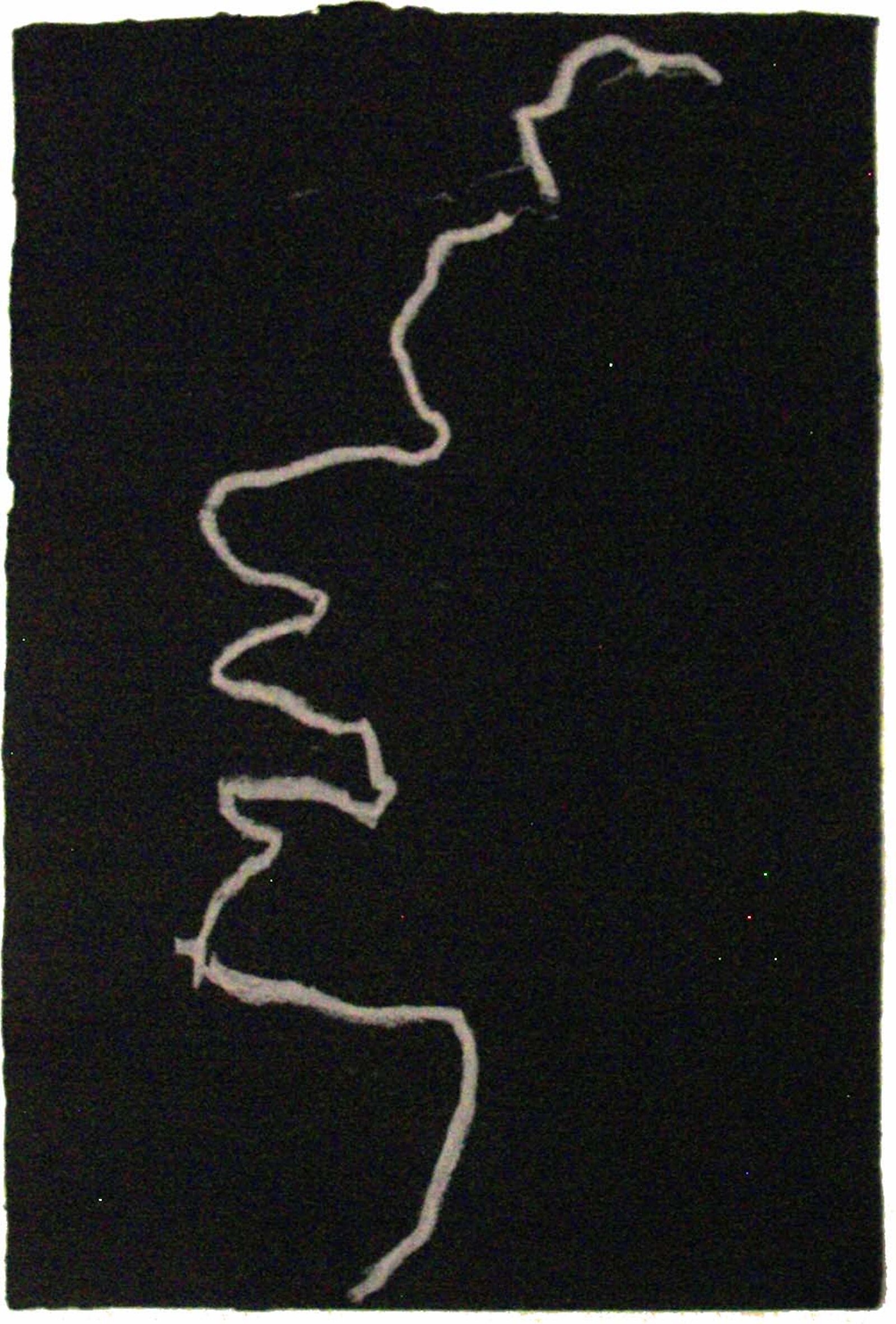

In parallel to this, Jonas has blurred the distinctions between things and beings, persons and animals, lines and gestures, organs and forms, abstraction and figuration. In front of the two performance drawings, there is a wall that, facing viewers, opens the exhibition. On it, placed side by side, nine sheets of black paper (JJ380-JJ388, all undated, all 33.9 x 21.5 cm) present a less-seen imagery in her work: a vertical line crossing the paper traces the profile of persons, likely men, in white or deep-blue pastel. This profile resembles a topographic representation of a river as it shapes the land, echoing some of the drawings of underwater waterways in the Rivers in the Abyssal Plain installation (2021) exhibited at the lower ground floor of the gallery.

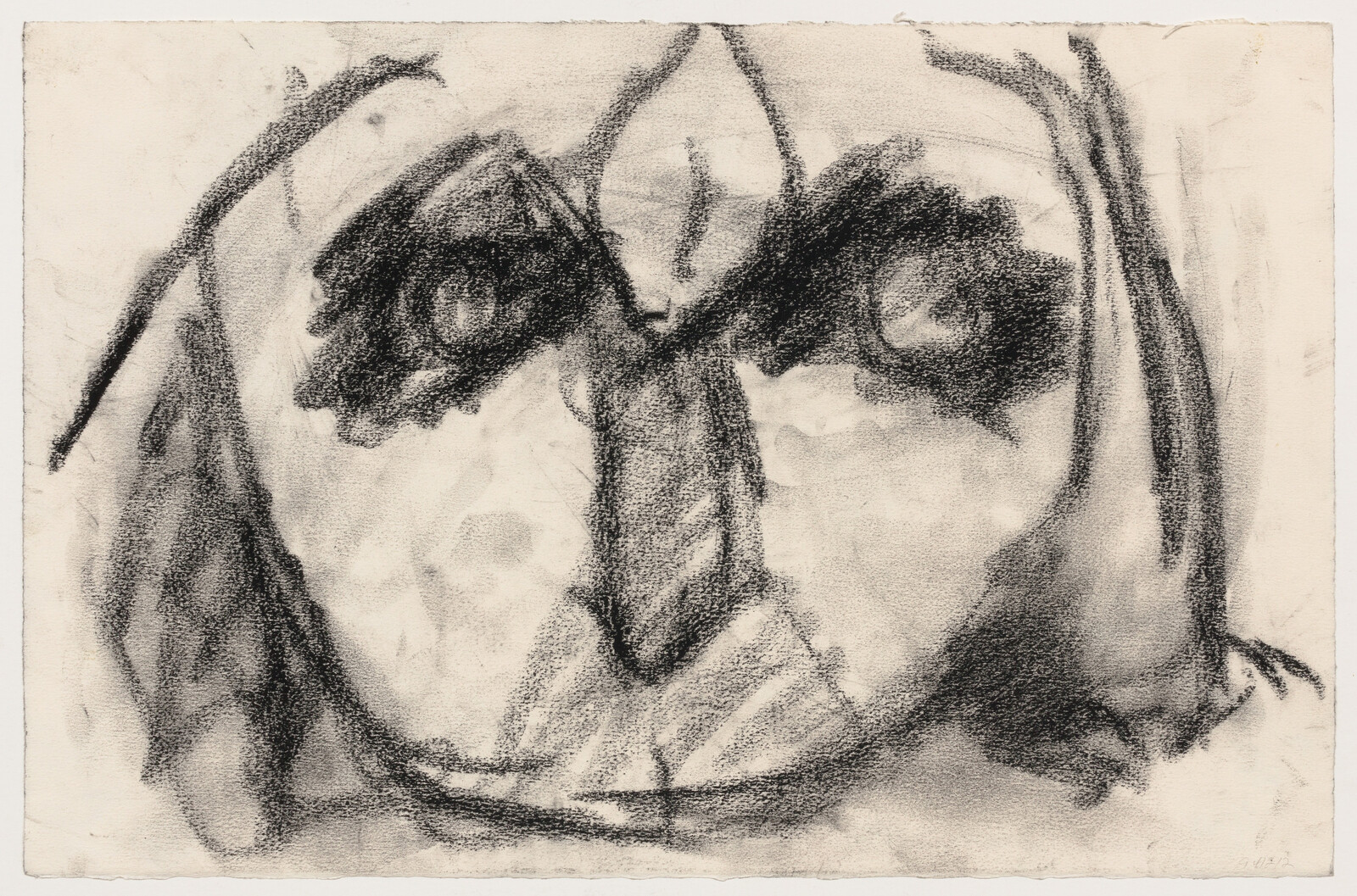

For visitors in the period of what Amitav Ghosh calls “The Great Derangement,” these drawings offer a reminder of how everything in the world is connected. And if our species is indeed capable of shaping geologic eras and formations (as the above drawings suggest), the configurations of landscape also reverberate in human and more-than-human forms: Jonas’s holistic sensibility creates hearts (JJ092, 1980s) that resemble dogs (JJ098 and JJ094, both 1970s), kidneys (JJ090, 1980s) that resemble vegetal beings (JJ419, undated) or hands (JJ086 c. 1976, JJ087, c. 1973) that resemble birds.

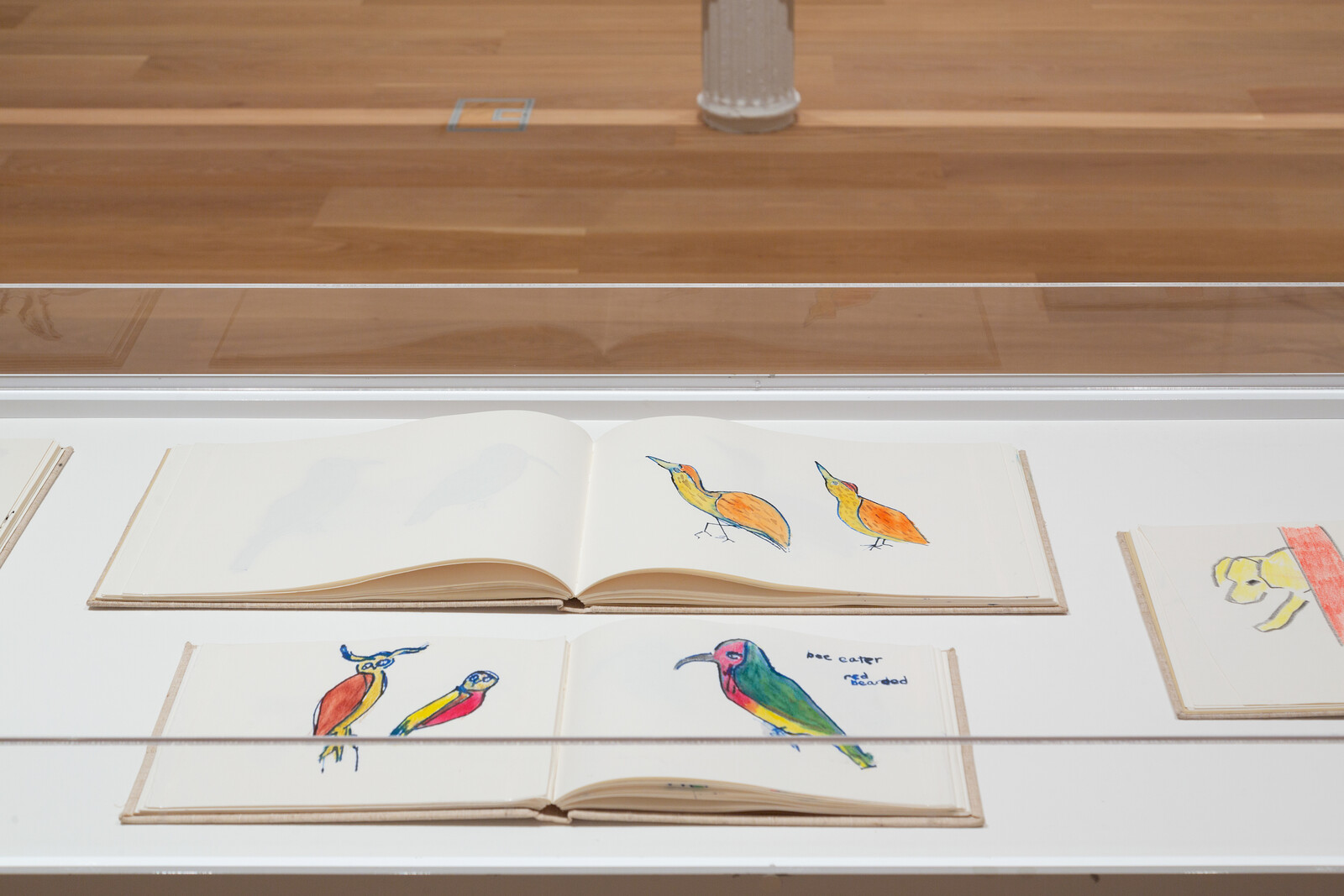

And birds that resemble toys and birds that resemble other birds (Jonas draws from both toy birds and live ones, so that it can be difficult to tell the difference). JJ126 (from the 1970s–80s) could be a wood sanderling; there is a series of dramatic owls with grave expressions from the 1980s and ’90s (JJ149, JJ156, JJ155); a profusion of joyful tropical birds from 2016, which coincides with Jonas’s residency and exhibition, curated by Ute Meta Bauer, at NTU CCA Singapore, where the artist visited the city’s large bird park (JJ126, JJ132, JJ140, JJ141, JJ142, amongst others); and several other creatures, some defined by a simple, uninterrupted black line (JJ423, undated). Others are much more detailed, and seem to exist in a fantastic, otherworldly universe, as in the case of the mysterious blue-and-brown cross between a dove, a hawk and a skylark, perched on a blue branch and waiting for a story to unfold (JJ125, 1980s).

Most of the drawings in the exhibition are of animals. Together with the flocks of birds are packs of dogs. Some are indistinct and others are familiar, as Zina and Sappho, two of Jonas’s former companions, can be found among them; her current dog, a white poodle named Ozu, appears in several of her videos but is less preponderant in her drawings. Next to the dogs, on the same wall, are many rabbits. Some dogs and rabbits share the same pointy, long ears, skinny legs, and elongated muzzle. Some rabbits are drawn in a realistic manner, others look cartoonish, and others recall other moments of Jonas’s exhibition history: the two rabbits who share a moon carrier (JJ063, 2010), for example, echo the “Double Lunar Rabbits” show at CCA Kitakyushu, Japan, also from 2010.

Fish, bats, snakes, bees, elephants, coyotes, camels, and kangaroo rats expand Jonas’s bestiary, attesting to how these assemblages of creatures real and imagined tell as much about themselves as about their author and her relationship to figuration, to performance and storytelling, and to simply being in nature and with animals. The pleasure that Jonas has in observing animals, the curiosity that leads her to spend hours looking at them in real life, in books, on television, in sculptures, and in films, is palpable. This sense of the time spent in the company of animals is well represented by the rhythm of the exhibition display, often slowly paced but at other times dense and fast. In its entirety, the show recalls the words and the spatial arrangement of Jonas’s poem Some Animals (2016), in which she described the animals that inhabit her studio:

Coyote

on the shelf

looking out window

Lion by the window

wood colors covered with writing

large Fox head Tiger Mask

papier mache orange with

red mouth black markings

top shelf

looking at Coyote

books nailed to table

surveillance

flash back

movement from mad to bird

Bird on branch shot stuffed

brown varied

Squat bird

green

purple

yellow

ceramic with interior bell2

“Animal, Vegetable, Mineral” runs concurrently with a retrospective of Jonas’s work at MoMA, on view from March 17 through July 6, 2024.

Joan Jonas, exceprt from “Some Animals,” in Animals, ed. Filipa Ramos (Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press and Whitechapel Gallery, 2016), 24–27.