In 1964, Nasreen Mohamedi, who moved to Mumbai from Karachi three years before Partition, wrote about the experience of continuous conflict. “I sit here and try and find a unity,” she wrote in her diary, “not between religions but between people and people.”1 The artist had returned to India the previous year from Paris, where she studied lithography following her first solo show at Gallery 59 in Mumbai’s Bhulabhai Desai Memorial Institute. A black-and-white photograph showing Mohamedi in her studio is displayed among others in “The Vastness, Again & Again,” curated by Puja Vaish at Mumbai’s Jehangir Nicholson Art Foundation. In the image, dated ca. 1959–1961, Mohamedi sits among abstract paintings resembling those she made in the 1960s (she rarely dated or titled her work). One such composition in “The Vastness” is an abstract blue-scale oil on canvas impression of what resembles a hazy waterside structure and its reflection, recalling the palette knife and roller compositions of V.S. Gaitonde, with whom Mohamedi shared an affinity for abstraction, Zen Buddhism, and Paul Klee.

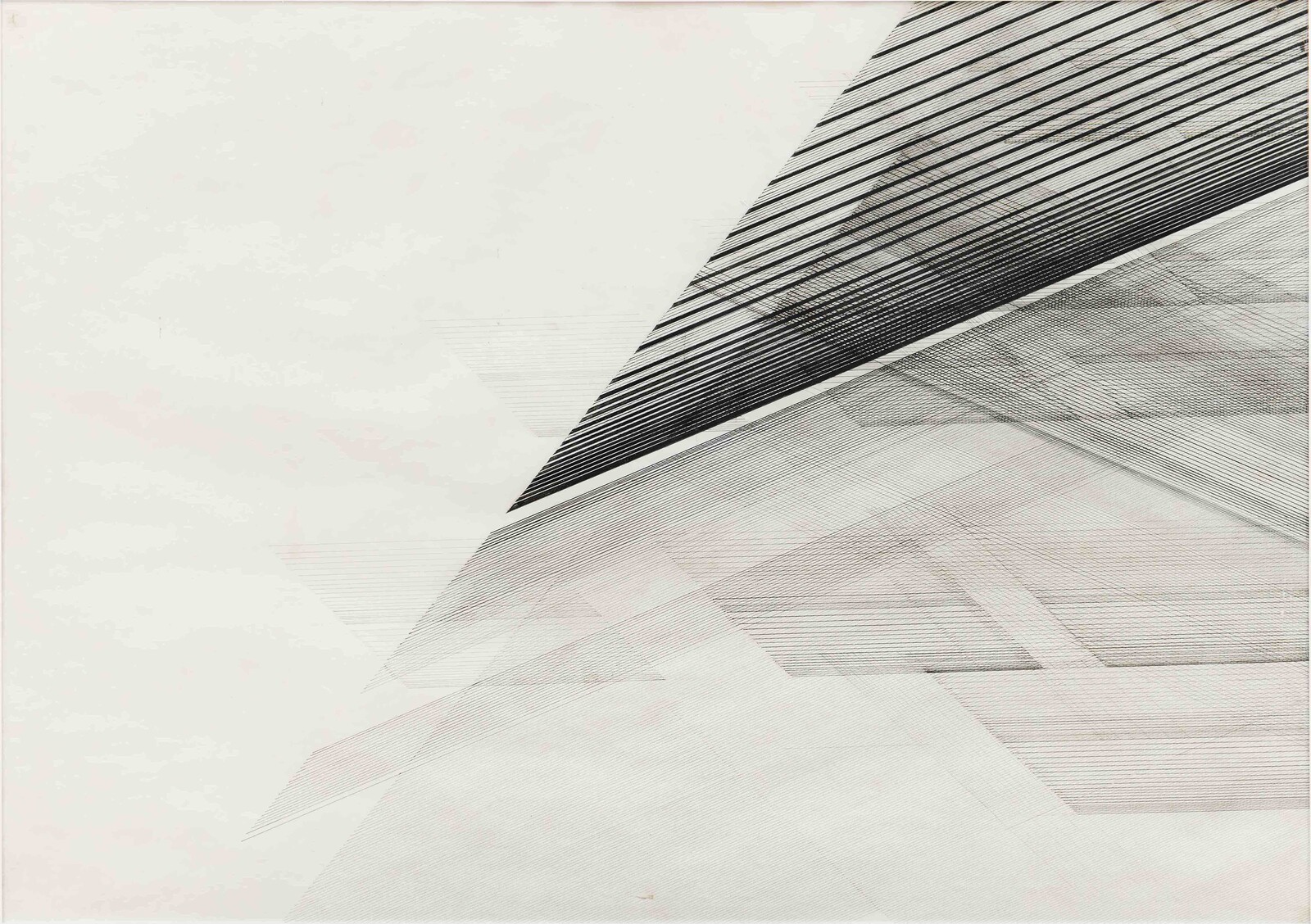

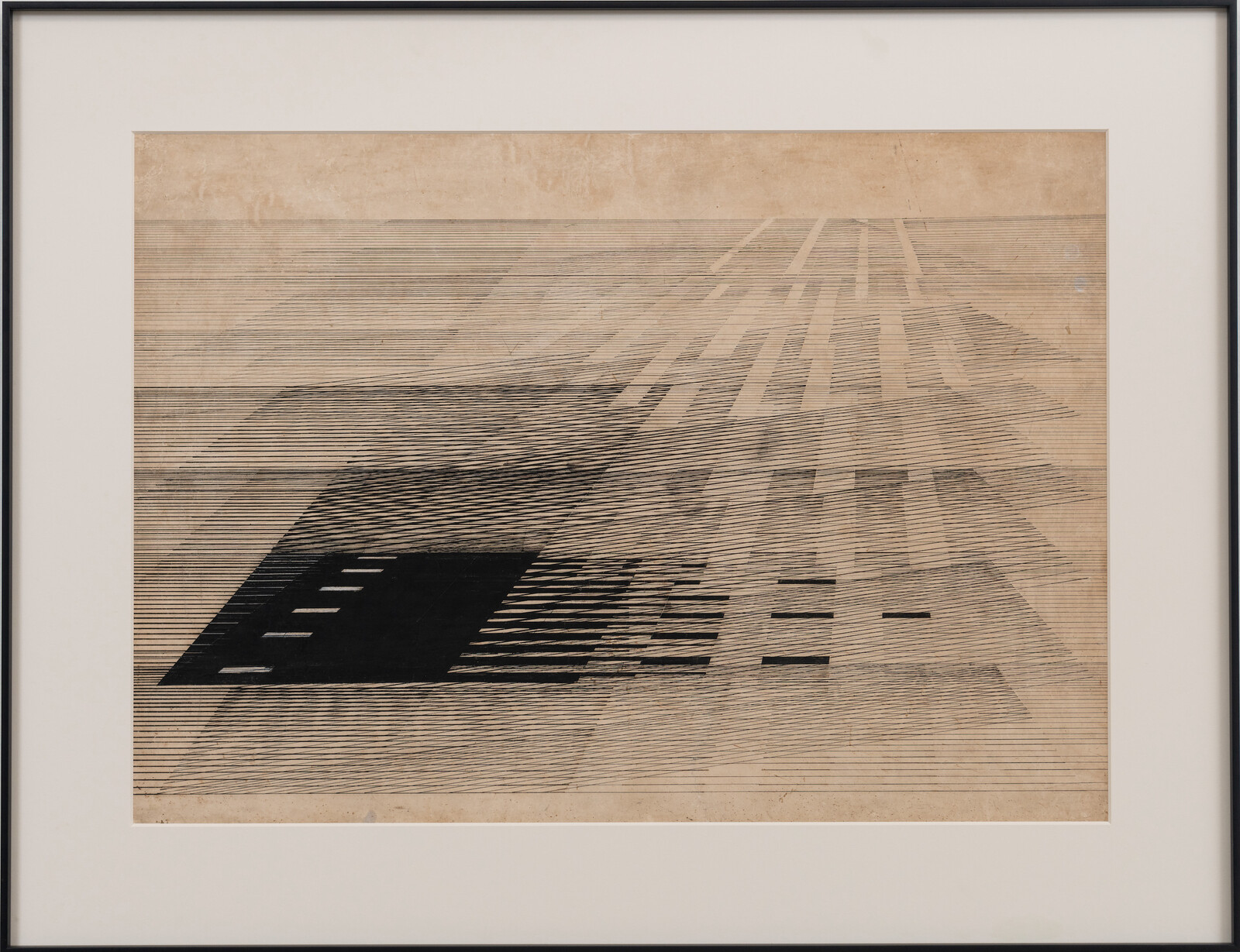

An untitled 1966 canvas by Gaitonde, of grey-scale marks on a blue horizon, is among the few pieces by Mohamedi’s contemporaries curated into this multi-dimensional reflection on the artist’s life and work. The show encompasses archival documents, ephemera, and artworks from across decades, but a sequence of ink on paper compositions from the mid-1960s tracks a seismic shift in her practice. A work from circa 1965 shows a web of abstracted dandelion and dried leaf–like forms moving across the page like neurons seeking connections, demonstrating a shift towards minimalism. As does the one beside it, where fluid strokes give way to exuberant, overlapping nemaline scratches, whose cumulative shape is echoed in the next painting, where leaves are etched into black-ink shrubs on a smudged grey ground. What follows is a pen-and-ink composition capturing the distillation of expressive marks into graphic lines that Mohamedi developed in the 1970s. With economic precision, vertical dashes form architectural rows diagonally up from the bottom right to the left of the image, where equidistant spacing transitions to a trail-off, as horizontal lines create connecting bands moving down from the top right on a diagonal axis, recalling visual impressions of sonic beats.

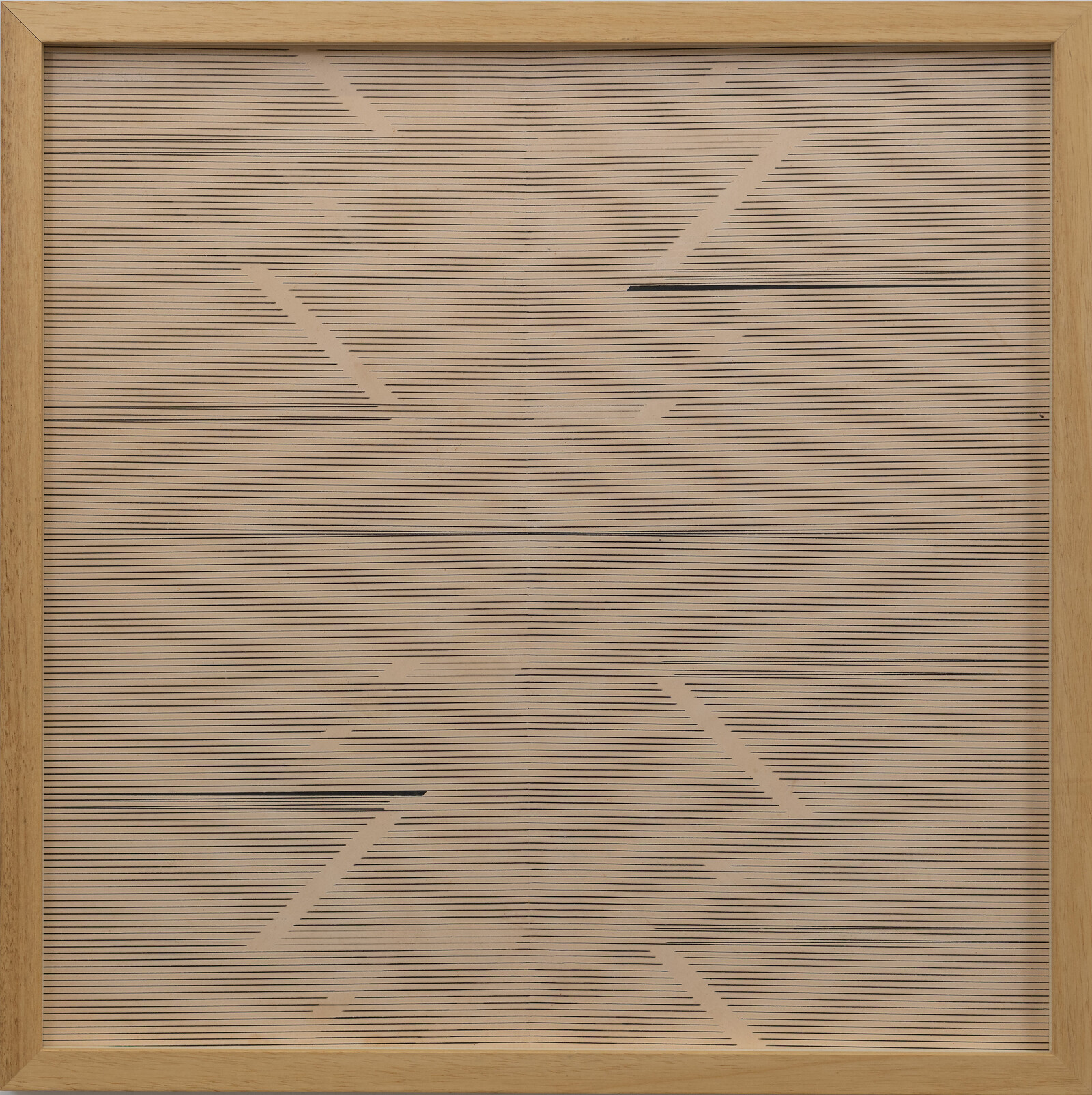

While these works reflect Mohamedi’s interest in the calligraphic line—Sufi poetry and Islamic art were among her many influences—“The Vastness” focuses on the mechanically printed script rather than its freehand forebear to emphasize the artist’s modernist impulse. In one vitrine, repeated letters forming block patterns on Arabic transfer sheets from Mohamedi’s archive echo the rhythmic densities that she developed across her ink and graphite line-based works, which evolved in the 1980s to incorporate curved lines and machinic shapes that seem to float on graph paper. Two black-and-white photographs hung above this script-based vitrine, of a path meandering to a vanishing point and a bird’s eye view of the foamy edge where water meets sand, extends Mohamedi’s study of spatial densities and linear geometries to the earthen contours she photographed.

Never exhibited in her lifetime, Mohamedi’s photographs of natural and built environments reveal an artist so immersed in the world that she had to zoom in. While subjects are often obscured by tight crops, one collection of small prints in “The Vastness” does offer immediately identifiable views, from the edge of bicycle wheels and feet on the ground, to one shot where a dog’s curved tail is isolated by a black rectangle drawn on like a viewfinder. Operating like notated sketches, each image outlines forms and angles that Mohamedi observed wherever she went; from Kihim’s coastlines to Le Corbusier’s modernist buildings at Chandigarh, which induced the same hypnotic feeling that Mohamedi experienced at the sixteenth-century red-stone Mughal city of Fatehpur Sikri. She mentions this in a letter presented among others addressed to artist Nilima Sheikh, who appears in photos nearby of Mohamedi with contemporaries like Bhupen Khakhar, and her Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda students. “BY THE SEA,” she begins, in lines written like concrete poetry, that gave this exhibition its title: “I CAN’T TELL YOU WHAT THIS PLACE / SPACE MEANS / THE VASTNESS / AGAIN + AGAIN ONE COMES BACK TO FIND NEW MYSTERIES.”

The idea of space as a site of untold possibility illuminates Mohamedi’s interest in the line as the connector of all things, which begins with the dot—what she described in 1968 as “leading to the same / A whole.” While acting like a coda to the drawings the artist spent a lifetime developing, this notion of a mark encapsulating a whole also explains why her geometries remain so enigmatic. Each composition is a distillation of the living environments that Mohamedi experienced: invocations of an ineffable and intersectional multidimensionality that reflected the unity she sought until her death in 1990. To embrace that inscrutable vastness, the artist’s ultimate inspiration, feels like the point. (Or the dot.)

Eleanor Clayton, “Seeking ‘A Blazing Reality’: Nasreen Mohamedi’s Photographs,” Tate (2014) https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-liverpool/nasreen-mohamedi/blazing-reality.