In an early scene of The African Desperate (2022), Martine Syms’s first feature film, her protagonist, a Master of Fine Arts candidate named Palace, hosts four professors in her studio for a final review. In turn, each teacher performs their own version of art pedagogy in Palace’s general direction, lobbing vague questions and cloudy critiques her way. “It’s all just so figurative,” comments Rose, the snidest, and most overtly racist, of the bunch (played perfectly by Syms’s longtime gallerist, Bridget Donahue). She gestures at the work: “It’s just a family, right?” Palace, skeptical and evasive up until this point, finally shoots back: “Haven’t you read Saidiya Hartman? Of course I’m responding to the African desperate.1 Staking my claim to opacity.”

Opacity is the name of Syms’s game in “Loser Back Home,” the artist’s first exhibition with Sprüth Magers, in her native Los Angeles. That scene was at the front of my mind as I toured the two floors, attempting to parse the show’s manifold logics, feeling a bit rebuffed at every turn. Opacity—and the right to stake one’s claim to it—was a concept crafted by Édouard Glissant in his Poetics of Relation (1990) as a means of protecting and preserving difference against the Western, modernist impulse to analyze, and thereby assimilate, its many Others. “Loser Back Home” certainly embodies that principle both in spirit and in form. Its thirty-five works have assembled a vast constellation of meaning, scattering countless allusions across its night sky. One can trace the connections and make out certain shapes, but their mythos remains a private one, residing deep within the artist’s inner world. Syms drops hints from on high, but rarely, if ever, divulges.

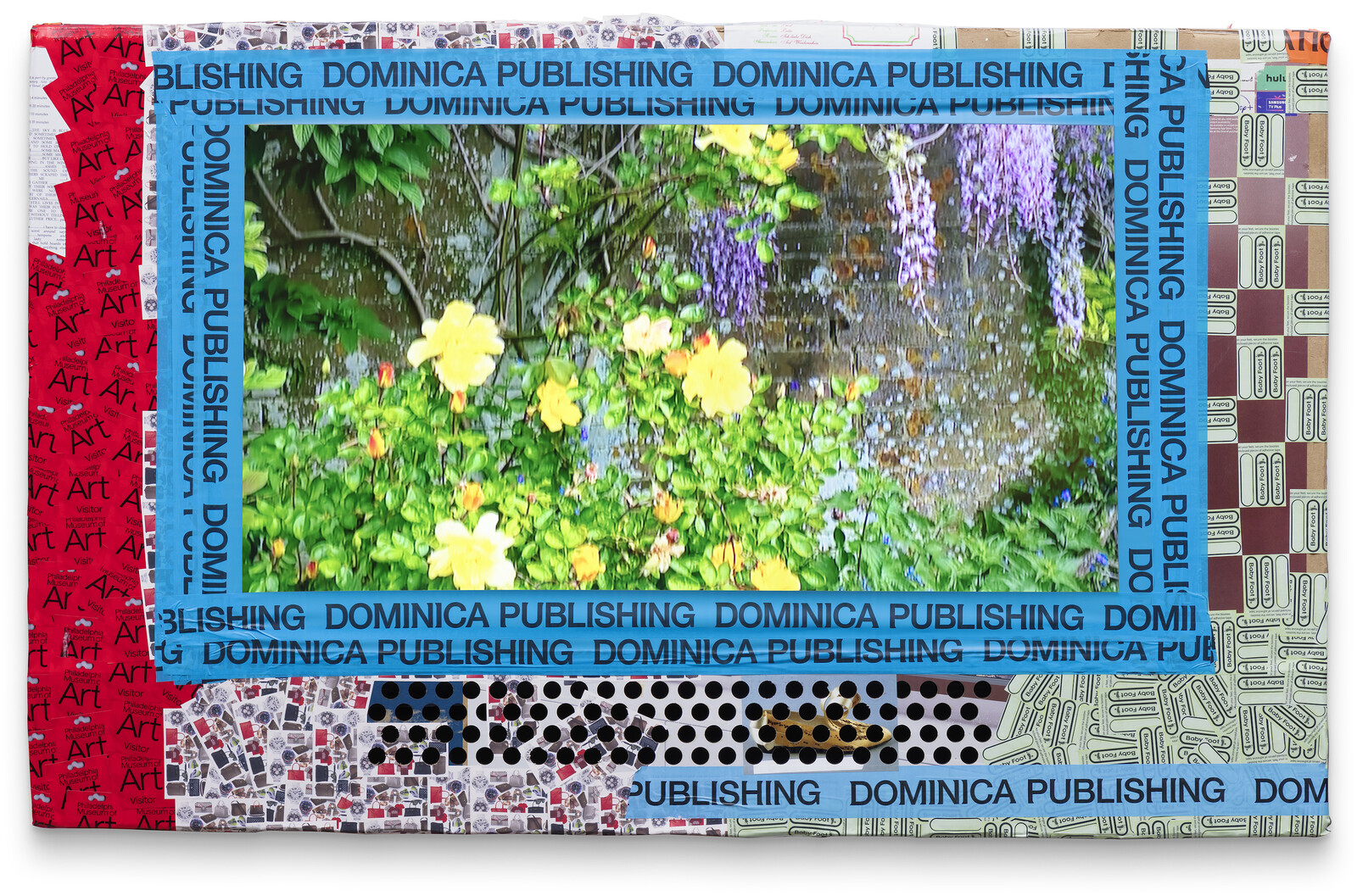

On a formal level, concealment is common: nearly every object—and there are many—is coated or covered in something else, keeping its raw material veiled. Peppered throughout the show are twenty cardboard boxes and ten retail paper shopping bags, each wrapped in glossy skins of adhesive vinyl, printed with repeating patterns of photographs, receipts, US Fish and Wildlife Service brochures, a New Jack City movie poster, a CalArts meal voucher, movie tickets, nametags, receipts with the artist’s name misspelled. Strips of custom-made shipping tape, reading “Dominica Publishing” and “Double Penetration”—the names of the artist’s publishing imprint and radio show, respectively—are layered on top. Syms also cuts and slices into these boxes and bags, creating miniature pop-up designs that resemble tiny staircases, or abstracted architectural forms—it’s hard to know for sure. They nevertheless nod to the dioramic, each box and bag becoming its own little arena.

Many of these works rest upon eight custom metal chairs, whose seats and backs are latticed with colored polyester straps. (Glissant, again? “Opacities can coexist and converge, weaving fabrics.”2) The straps are printed with sibylline, all-caps words and phrases, only a few fragments legible. I could make out “what’s coming up?,” “Mushrooms MDMA coke acid,” something about exes and lovers. Floor-to-ceiling photographs, also printed on vinyl and showcasing the stuff of daily life, encase the second-story walls. Four patchworked compositions of sewn-together tote bags, T-shirts, and other textiles are pulled across aluminum stretchers. A sixteen-foot-wide canvas panel, painted a flat canary yellow, neighbors another one featuring a simple line drawing of a few buildings behind a city wall. The latter balances atop the mouth of a large glass growler, filled with bills and coins of different currencies. Nearby, a couch is covered in moving blankets, quilted together. Eleven graphic T-shirt, sweatshirt, and hat designs, for sale to the public (70–90 dollars), line another hallway, stuck to the wall with that same shipping tape.

We’ve seen many of these tactics from Syms before, but never on this scale. She has always approached art like an essayist; disparate elements fall into place under her own bespoke grammar, syntax that serves a larger idea. The linearity of time-based media is ideal for this project, and Syms has proven herself a master of the format. But imposing a rhetoric upon over fifty objects in a sprawling space is a different task altogether. By comparison to her video art, tacking idioms and images to the surfaces of other things often feels like simple arithmetic. Syms is by no means obligated to translate her vast lexicon of leitmotifs for us, but any artist must argue for the specificity of her chosen mediums lest they feel arbitrary, a bit too opaque, a snarl of signs and semantics turned into stuff for stuff’s sake.

There are four video works in “Loser Back Home,” and they will satisfy any visitor’s desire for a dash of depth, candor, humor, or human experience. Three of them are small, short, and encased in objects, as if smuggling their way in. One twenty-six-second loop of two police cars in a parking lot nestles in the small ID pocket of a Prada garment bag, peeking through a window of clear vinyl barely bigger than a business card. Two play on monitors nested within cardboard-box frames: one involves security-camera footage of a cop outside Syms’s studio, buzzing her intercom, while in the other, the artist chats about a romantic entanglement over a breezy montage of footage, music, and pre-modern art. Only one, i am wise enough to die things go (2023), is a centerpiece in its own right, displayed across two composited flatscreens. Over the course of its fourteen minutes, a young woman in a green-screen studio is subjected to a range of shifting environments, stuck somewhere between reality and virtuality. Her exasperation is palpable as she tries to negotiate with her Sartrean surroundings. Like many of Syms’s avatars and protagonists, this woman wears a shirt with “To Hell with My Suffering” printed on its verso. It’s only visible when she turns her back to the camera, briefly flashing its bold white letters, but the artist’s own, rather existentialist message remains clear. Nearby, that same shirt is taped to the wall and on sale for 70 dollars. Oddly enough, it felt like the most generous gesture in the show; Syms may be hiding from the hell of other people, but if we feel the same way, we’re certainly welcome to join her.

This is a slip, of course; Hartman writes about the “diaspora.”

Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2021), 190.