At 15°53’N 78°38’W in the Caribbean Sea lies the remote Bajo Nuevo Bank. Population: zero. Formerly claimed by Jamaica and Honduras, this reef and islet cluster is administered by Colombia, though Nicaragua and the US both insist that it belongs to them. Devoid of citizenry, the island is defined by its strategic and economic value to competing nation states.

Bajo Nuevo and ten other islets or atolls comprise a category of US territories known as the Minor Outlying Islands.1 As the Center for Land Use Interpretation (CLUI) describes them in “Unoccupied Territories: The Outlying Islands of America’s Realm,” an online exhibition comprising images from Google Earth alongside texts describing the islands, they are the “tattered fragments of [US] dominion.” To the CLUI, a non-profit producing interdisciplinary work at the intersection of art and geography, these unorganized, mostly unincorporated, mostly uninhabited, and sometimes disputed geopolitical fragments demand investigation.

The islands’ histories of abuse by imperial ambition and damage by global war are distinct, but they share absorption into US jurisdiction under the Guano Islands Act of 1856, a federal law that permitted Americans to claim the scantest ocean topography on the premise that it was stateless and held a cache of guano. A few things about guano: it’s bat shit, it’s bird shit, it can explode. The mid-nineteenth century saw a surging enthusiasm for seabird guano because of its nutrient-rich composition. Great for fertilizer and gunpowder, Americans couldn’t get enough of it. That the Guano Act encouraged a whole mining industry is a testament to the abundance (and quality) of excrement that existed on the Outlying Islands. What the act failed to anticipate was resource depletion and its aftermath.

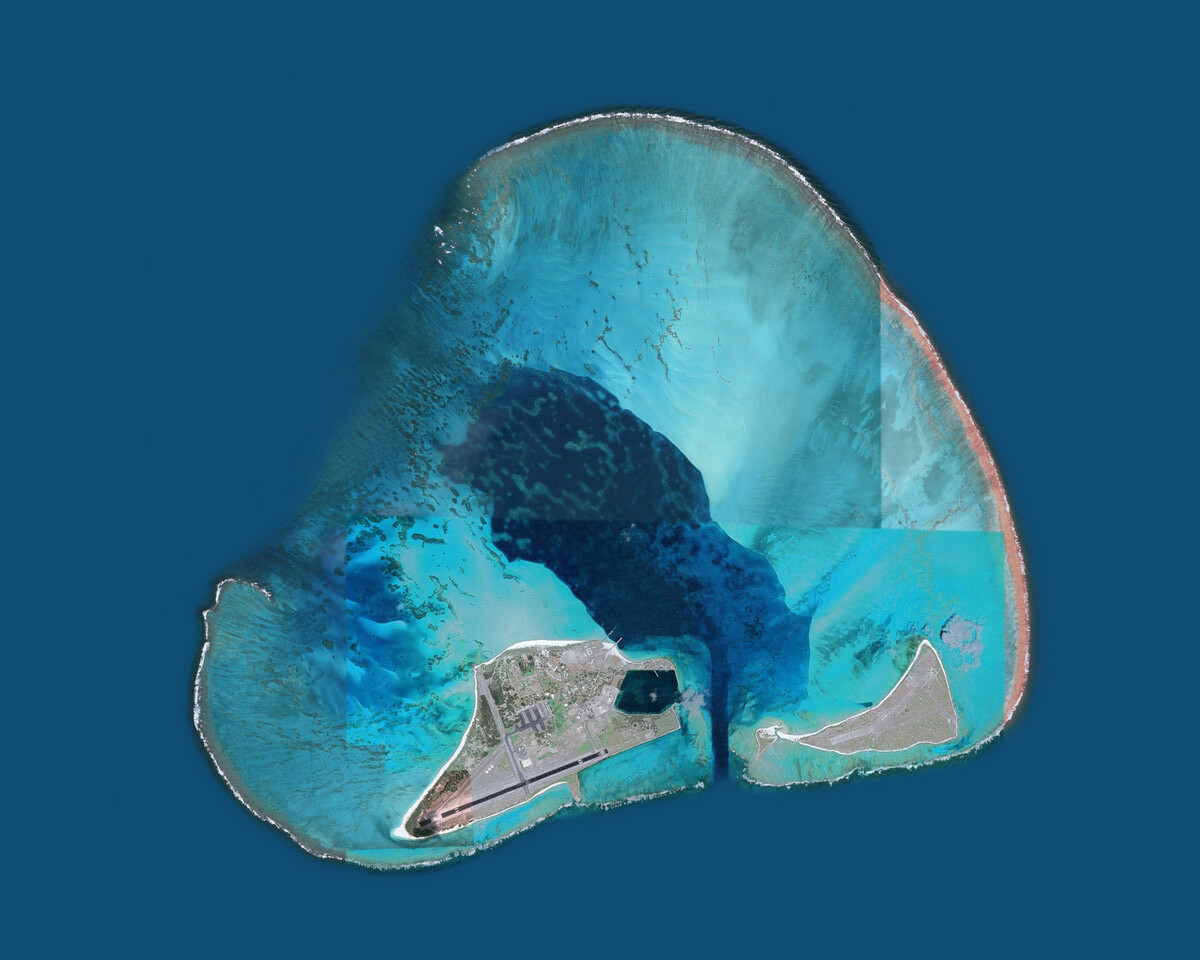

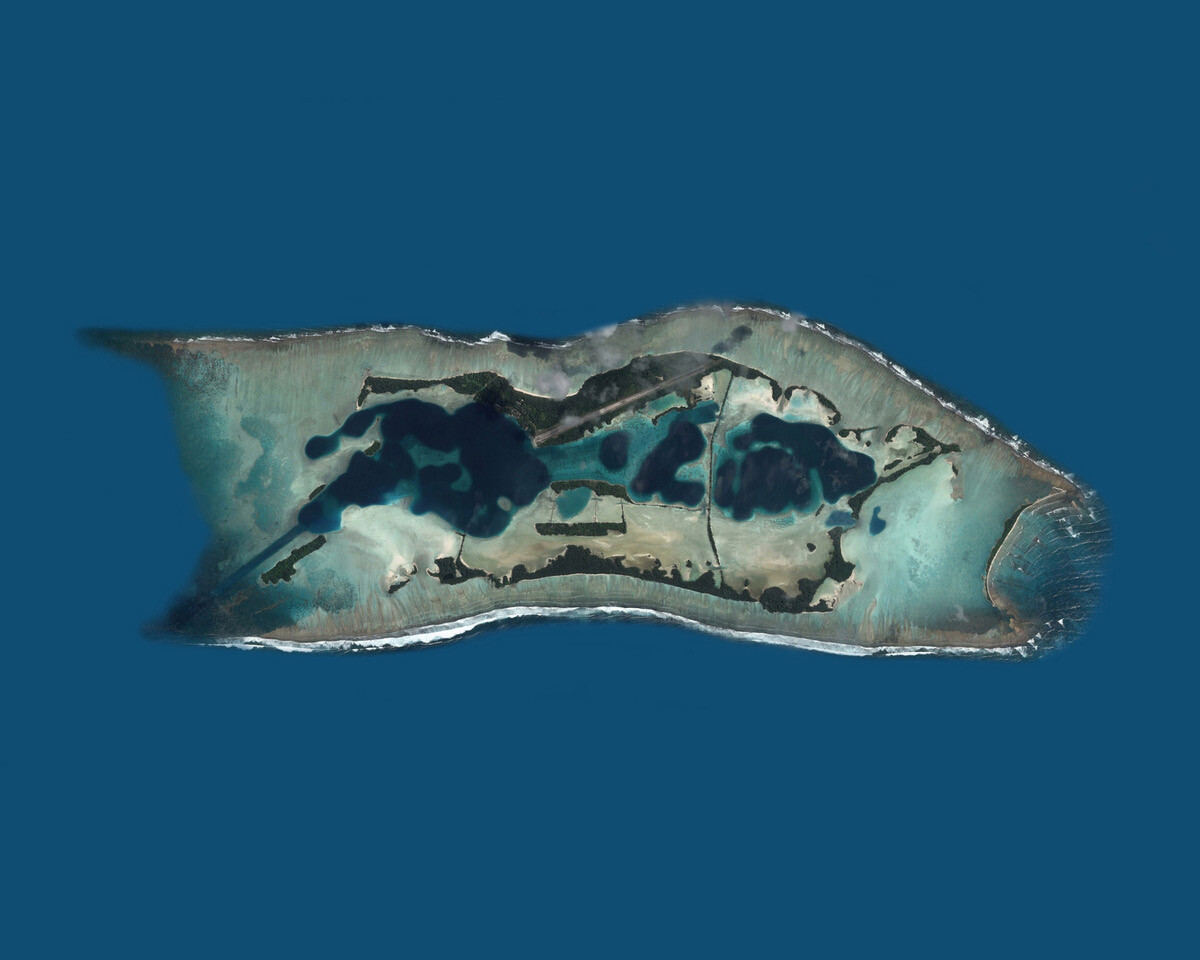

CLUI catalogs the sites that held US interest in Google Earth images set against a Chathams Blue background, which emphasizes the islands’ geographical isolation on the high seas and makes both land and water extra alien. This charmless, bureaucratic shade of blue enhances the clinical presentation of “Unoccupied Territories” and acknowledges the affective detachment that occurs when cartographic representation renders distant locales abstract. Such distortion allows opportunists, like those who authored the Guano Act and those who acted on its permissions, to exploit the abstraction born of distance as a moral palliative in their quest for power, domination, and profit.2

The presentation format itself—a single webpage in which images and text are vertically arranged in an epitome of brutalist web design—seems determined by the conditions of the available data and the limitations of the instruments that provided it (i.e. Google’s eye in the sky) and predetermined by CLUI’s taste for no-frills infotainment. Their 2019 show “Continental Divide,” about the geographical boundary which runs from Alaska to Mexico and marks the boundary of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, featured super-annotated maps that appealed to cartographers and hikers alike; the centerpiece of “Voice of America: The Long Reach of Shortwave,” also from 2019, was a radio that transmitted live broadcasts from the last shortwave transmission plant in the US. Without the didactic captions of “Unoccupied Territories,” viewers might have otherwise struggled to name the blob that looks like an opal on a rubber dissecting pad. This penchant for enticing viewers via text-heavy graphics may discomfit those who deem art and education friendly yet distinct disciplines. In less skilled hands, such austerity could have killed the project. Yet CLUI’s honed word-and-image delivery method inspires curiosity.

For anyone on board with the center’s call to “[understand] the nature and extent of human interaction with the surface of the earth,” and belief “that the manmade landscape is a cultural inscription that can be read to better understand who we are and what we are doing,” then this hybridized approach marks the gold standard for research as creative practice. “Unoccupied Territories” advances CLUI’s mission, and it does so with results that an IRL version—as the exhibition was originally intended—might not have effected.3

This online exhibition comes at a moment when everyone is under order to be an island, despite John Donne’s adage; when the idea of being marooned has gained new currency; and when the computer is both a prison and an escape route of our own making. While it is fascinating to read CLUI’s account of Jarvis Island’s residents (dubbed “re-colonists”) who were paid by the US to stay on the island during the 1930s, or the outdoor shower built for Amelia Earhart on Howland Island, it is all the more pleasurable to conduct one’s own further investigations online in the spirit of experimental geography—to do one’s own land-use interpretation.

Give yourself over to this information rabbit hole, and you discover incidental poetry in the International Organization for Standardization codes assigned to the Minor Outlying Islands.4 Wonder how we, as a species, have survived for so long by scrutinizing Johnston Atoll’s record as a nuclear test site, biological warfare test site, chemical weapons storage site, and Agent Orange storage (and spillage) site. Consider a lagoon that is contaminated forever. In a macroscopic sense, “Unoccupied Territories” traces histories of aviation and intercontinental warfare. At its darkest, it is about the continuing and measurable impact of US extractivism, capitalism, and imperialism on the present. By reversing cartographic disconnection, the exhibition brings us uncomfortably close to a concrete understanding of our shared proximities.

Online viewing room

“Unoccupied Territories: The Outlying Islands of America’s Realm”

The Territories of the United States consist of the five permanently inhabited territories (Puerto Rico, Guam, the US Virgin Islands, the Northern Mariana Islands, and American Samoa); and the nine Minor Outlying Islands plus the disputed Bajo Nuevo Bank and Serranilla Bank.

For another example of artists interrogating the connection between guano and American colonialism, see documentation of Allora & Calzadilla’s exhibition “Foreign in a Domestic Sense,” which was held at Lisson Gallery London from September 22 to November 11, 2017, and focused on Puerto Rico’s geopolitical conditions as an inhabited, unincorporated territory of the US: https://www.lissongallery.com/exhibitions/allora-calzadilla-foreign-in-a-domestic-sense.

A physical exhibition of “Unoccupied Territories” was mounted at CLUI’s space in Culver City, California. At the time of writing, its doors remain temporarily closed to the public for reasons of pandemic health and safety.

ISO 3166-2:UM-67 Johnston Atoll. ISO 3166-2:UM-71 Midway Atoll. ISO 3166-2:UM-76 Navassa Island. ISO 3166-2:UM-79 Wake Island. ISO 3166-2:UM-81 Baker Island. ISO 3166-2:UM-84 Howland Island. ISO 3166-2:UM-86 Jarvis Island. ISO 3166-2:UM-89 Kingman Reef. ISO 3166-2:UM-95 Palmyra Atoll.